AMMAN // Ten years ago, Muneer Rahahleh and his wife, Wafa, lost their son Mohammad to an infection that struck his adrenal gland. He was 19 years old and in his first year of university, studying to be a doctor.

When the 40-day mourning period ended, Muneer and Wafa began talking of having a baby boy. However, Muneer was 46 years old and Wafa was 38, and she had already given birth to three daughters. Keen to ensure they would have a boy, the couple turned to a fertility centre in Amman.

With the aid of an in vitro medical procedure that allowed the family to choose their baby's gender, they had another boy and named him after his dead older brother. The boy, now nine, provides the couple with a kind of solace that having another baby girl could not have supplied.

"He reminds us a lot of his brother. He looks like him, behaves like him and he even loves Coke, pizzas and hamburgers just like him. His presence has helped us deal with the pain," Muneer said.

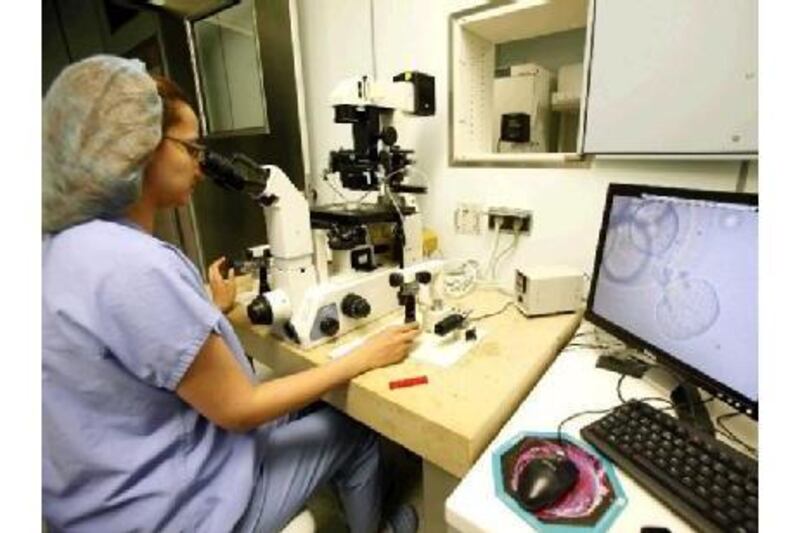

New technology related to in vitro fertilisations that now allows physicians to identify the gender of the embryo before placing it in the womb is gaining a foothold in Jordan, even as religious scholars, ethicists and members of the medical profession remain divided over its use.

What started as a procedure in the mid-1990s to prevent genetic diseases has become a service at the country's five fertility centres, sought mostly by couples desperate for a baby boy to carry on the family's name and to keep inheritance within the family.

Zaid Kilani, the obstetrician and gynecologist who introduced the procedure to Jordan after pioneering in vitro fertilisation the country in 1986, said: "What we are doing here is selecting embryos to define gender. The argument should not be whether it is ethical or not, but whether it is justified."

Dr Kilani, who is also director general of Farah Hospital, the largest private fertility centre in the country, said: "We select our cases. There are no guarantees of success. The procedure is rather expensive, stressful, and there are dangers of multiple pregnancies. We only recommend it for those who really need it. For example, when there is a loss of a child and a desire to have another of the same gender or a family with children of only one gender or when a woman is in her mid to late thirties."

There are no nationwide statistics about the use of the gender selection procedure, but last year Farah Hospital administered it to 500 women, including 180 Jordanians, an increase from 380 cases in 2007, Dr Kilani said. The procedure's cost, about US$4,000 (Dh14,700), makes it unavailable to all but the affluent.

Those who support the procedure say it prevents polygamy and reduces the number of attempts by parents to have a baby boy. Nael Abaza, an obstetrician and gynaecologist who performs gender selection at the Arab Centre for Genetics and IVF in Amman, said: "There are men who take another wife if the first doesn't conceive boys."

Opponents of gender selection through in-vitro fertilisation say that in many cases couples are resorting to it for the wrong reasons.

Isam Shriadeh, head of the obstetrics and gynecology department at Jordan's ministry of health, said widespread use of the procedure would pose societal risks.

"I only recommended it when there is a genetic predisposition to diseases related to gender. If the practice continues, it will be disastrous for us," Dr Shriadeh cautioned. "As an Arab society, we'll bear the brunt of it 30 or 40 years from now when the sex ratio has tilted heavily towards males."

There is evidence that Jordan's doctors are divided. According to a 2009 study of attitudes of graduating medical students towards using sex-selection techniques at the Jordanian University of Science and Technology, a narrow majority said they should be restricted. The study said more than half - 54.7 per cent - of 254 doctors surveyed opposed their use except on necessary medical grounds.

Muslim and Christian officials in Jordan have condemned the practice. A fatwa last month by Jordans's department of Ifta said the procedure is not sanctioned and urged couples to be content with what God grants them, "be it a boy or a girl".

Rifaat Bader, an ordained priest and spokesman for the Roman Catholic Church in Jordan, said: "Anything that is scientifically possible does not mean that it is ethical or acceptable.

"The foetus should be the fruit of a [personal act] between a married couple. Children are a blessing from God and the procedure is one that discriminates among sexes."

The Jordanian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists is in talks with the government over regulating the practice. One proposal calls for allowing it for families with a minimum of two children of the same gender when the mother is in her late 30s.