CAIRO // Perhaps no other institution in Egypt has more symbolised the harrowing side of life under President Hosni Mubarak than the police.

Police officers and their agents went undercover in workplaces and cafes to ferret out the government's opponents and, according to local and international human rights groups, routinely practised torture in their jails.

Though hardly all police were guilty of committing such offences, the institution became so tainted that the mere sight of any policeman on the streets was enough to set the stomachs of many Egyptians churning with fear. No more.

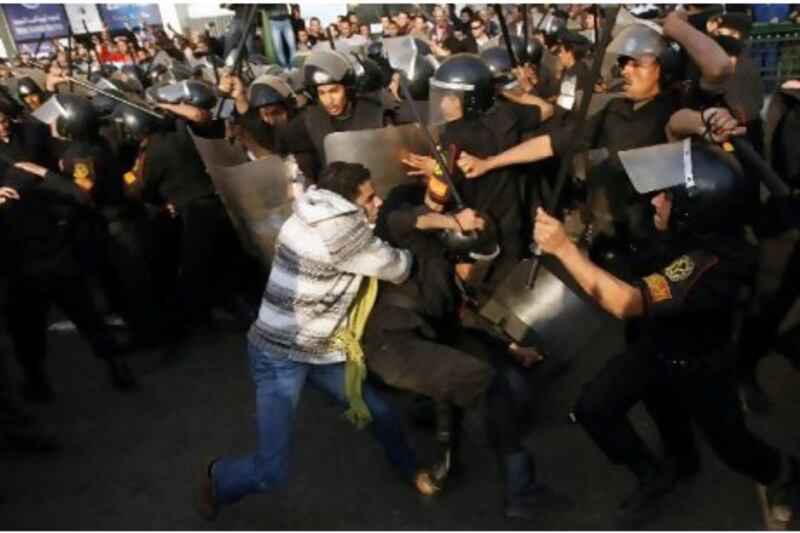

On January 28,- a day dubbed the "Day of Rage" by protest leaders, anti-government demonstrators struck back, leaving in their wake at least six police stations and scores more police vehicles burned out across the capital.

Since then, except for traffic officers, uniformed police have melted away from the streets, and army soldiers and tanks have taken their place. While it is unclear whether the police were ordered to redeploy or simply acted on their own, many Cairenes say they feel safer and freer as a result.

"When you don't have them around, when you're not scared anymore, you can smile," said Magda, 50, who was entering Tahrir Square on Wednesday with her daughter, 25-year-old Norham, to take part in the protests.

Indeed, taxi drivers in the capital now revel in their newfound freedom. Some even enjoy thumbing their noses at traffic officers when they have a chance, which would have been unthinkable only two weeks ago.

"If one of the [expletive] guys does anything, I promise I will kill them," spat one driver.

____________________________

Egypt's two weeks of unrest

____________________________

In the western governorate of Al Wadi Al Gadeed, demonstrators earlier this week torched a police station and a prison, Al Ahram newspaper reported on Wednesday. They also set alight records of traffic violations as well as paperwork at a fire department and the local prosecutor's office, it said.

Amr al Shobaky, the director of the Alternative Forum for Political Studies, an independent think tank, said: "The people feel they have the upper hand against a police force that represented the republic of fear, the old regime."

Anger has festered for years at this "republic of fear," highlighted by such instances of brutality as the case of Imad Kabir, a bus driver who in 2006 was filmed being sodomised with a rod at a Cairo police station. The policemen distributed the video to his friends and colleagues as a means of intimidation, but it instead generated backlash against the government when it was published on the internet.

Increasingly, Mr Shobaky said, Egyptians had become fed up with such incidents and the president's continued justification of his security services for maintaining stability.

Mr Mubarak and his security system have been aided by a constitution drafted to favour it and emergency rule, in place for much of the past 45 years. And despite pressure from US officials, the man tapped by the president to lead a political transition, vice-president Omar Suleiman, so far seems reluctant to end it.

Mr Shobaky said: "Mubarak has always called himself a man of security, but his regime has been an apolitical one based on security and stability without any other political vision. So the role of security was to be everywhere, and it was an institution dedicated to preserving itself."

Anger at this came to a head after the alleged killing of Khaled Said by police in June. The 28-year-old native of Alexandria reportedly obtained footage of policeman dividing up a cache of marijuana, and was then beaten to death by the officers after he posted the video on YouTube. A Facebook page in his honour, "My Name is Khaled Said", is believed to have sparked the current wave of anti-government protests.

No one outside the regime's security apparatus knows if the withdrawal of the police is temporary, let alone if the police and security forces have been permanently crippled.

There were signs this week that the police, which operates under the Ministry of Interior, were trying to remake their image.

Authorities announced that prosecutors were weighing charges against Habib el Adly, recently removed as interior minister. The charges, including murder, are related to the killing of protesters by security officers during the unrest.

That is still not enough to allay completely the worries of those who fear the re-emergence of the police and doubt that the army, in contrast to the police, is the nation's saviour.

Indeed, concern among the protesters about the military's loyalties has increased. While many see the soldiers as protecting them from plainclothes police and supporters of Mr Mubarak, the military is also suspected by rights workers of orchestrating a recent wave of arrests against them.

Sherif Azer, who works at the Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights, said: "They are mostly detained by the military intelligence or the military police, with the collaboration with the state security bodies."

He also said there was potential for the police to revive their old tactics if protesters stopped exerting pressure on the government. Their disappearance immediately after January 28 suggested they were ordered to pull back, not destroyed as an institution.

In fact, Mr Azer said, "some police officers are in the main square. They are coming back."

Fear of a return to the old ways is why Hussein Youssef, 19, a pharmacy student camped out in Tahrir Square, vows to stay until Mr Mubarak and his allies leave.

"If we stop now, the old government will come back," he said. "The police will start beating people again and the revolution will fail."

He and his friends over the past two weeks have battled back the president's supporters, many of whom they say are plainclothes policemen. At least 232 people have died in the fighting in Cairo alone, according to the New York-based Human Rights Watch.

To leave the square now, Mr Youssef said, would allow police to return and represent a defeat for all that the people in Tahrir Square fought and died for.

"That would mean no more freedom," he said.