JERUSALEM // Three years ago, Sawsan Salameh was a teacher at a girls' high school in the Palestinian village of Anata in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, dreaming of earning a doctorate in chemistry. So the devout Muslim was excited when she was accepted into the doctoral programme of Israel's Hebrew University, located in Jerusalem just four kilometres west of her home in Anata, with a full scholarship and research salary. After all, no university in the West Bank offered doctoral degrees, and by studying in Jerusalem she could stay close to her family.

But her dream was nearly dashed because of an Israeli army ban on permitting new Palestinian students to study at Israeli universities. She turned to Gisha, an Israeli group advocating Palestinians' freedom of movement, which petitioned the Jewish state's Supreme Court on her behalf and demanded a reversal of the ban. While the army has made an exception in the meantime and granted her a permit to enter Israel to study, her petition is still pending on the overall ban. Ms Salameh, who just completed the second year of her doctorate, hopes to become a trailblazer for other aspiring Palestinian academics.

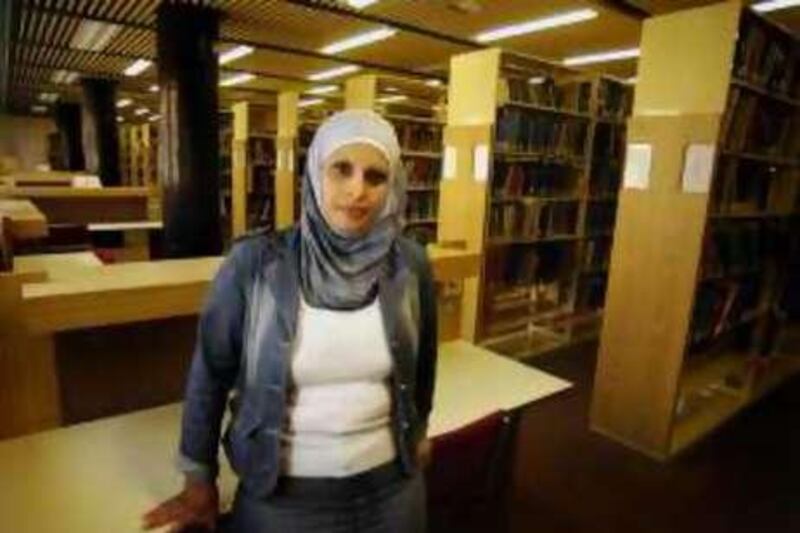

"My case in the court is for the others now," said the 30-year-old as she relaxed in a café at Hebrew University on a hot day, wearing a blue headscarf and clad in an ankle-length skirt and denim jacket. But Ms Salameh remains a rare case of success. Just weeks before the start of the academic year at Israeli universities in October, only a handful of Palestinians will gain access to attend them. Their numbers have dwindled from the hundreds during the 1990s, to the dozens after the eruption of the second Palestinian intifada in 2000, according to Gisha. Israel turned the study restrictions into an overall ban in 2005, citing security reasons, and only in recent months has indicated it will allow some students in.

The policy reflects more than Israel's limitations on Palestinian freedom of movement. It also shows the barriers faced by Palestinians seeking higher education. Universities in the West Bank or Gaza Strip do not offer doctoral degrees and lack many master's programmes. Furthermore, Israel is the only option for those who cannot afford studying abroad, or for women whose traditional families do not permit them to travel far by themselves for an education.

In the Gaza Strip, Palestinians are totally forbidden from accessing universities in Israel, and hundreds are prevented from leaving the region to study in other countries. Israel considers the coastal enclave hostile territory after it was violently taken over by the Islamic group Hamas in June 2007. The state, which withdrew its troops and civilians from Gaza in 2005, still controls most of the area's border crossings and mainly allows patients needing medical care to exit. Moreover, Egypt's border crossing in southern Gaza is only occasionally opened.

Sobhi Bahloul, 45, became the first Gazan ever to attend Tel Aviv University when he was admitted to a master's programme in English four years ago. But Mr Bahloul, a fluent Hebrew speaker who spent the early 1990s teaching Hebrew to Jewish immigrants in Israel, has not been allowed to travel to Tel Aviv to start a doctorate since the Hamas takeover. "My colleagues at the university used to call me the Palestinian ambassador - that's what I had hoped to become one day," said Mr Bahloul.

He said he had been "really frustrated" by Israel's policy, which is triggering "more hatred for the Israeli people from Palestinians". In the Israeli-occupied West Bank, governed by the western-backed Fatah party, Palestinians leave through Israel's crossing with Jordan mostly unrestricted to study abroad. But for those needing the proximity of Israeli universities, most permit requests have been fruitless.

In a response in March to Gisha's petition, the Israeli army produced new rules for granting Palestinians from the West Bank study permits. While they no longer impose a ban, they nevertheless infuriated rights activists and Israeli academic officials alike. The criteria limit the number of Palestinian students at any given time in Israel to 70, require them to study subjects that do not hurt Israel's security and obligate universities to submit letters to the army justifying their decisions to accept the students.

Activists say the new rules violate Israel's obligation to facilitate the education of Palestinians living under occupation. They add that the procedure also infringes the academic freedom of Israeli universities and needlessly goes beyond the army's security duties. The policy, they stress, could also provide ammunition for institutions abroad to curtail partnerships with Israeli universities or altogether ban them.

"The rules make the military into the supreme admissions committee for Israeli universities," said Sari Bashi, director of Gisha. The criteria also elicited criticism from the top officials at six Israeli universities, who dispatched a letter in May to Israel's defence minister and demanded the army stick to individual security checks and leave the academic criteria to them. Tsevi Mazeh, 62, is one of five Jewish Israeli professors who in July asked the Supreme Court to allow him to join Gisha's petition against the policy.

The professor of physics and astronomy at Tel Aviv University said he was especially angered with the army's quota on Palestinian students because it reminded him of limits placed on the number of Jews attending universities in Eastern Europe before the Second World War. "It's in the interest of Israel to encourage Palestinian students to come because they will create a bridge between us and the Palestinian society," said Mr Mazeh, a grey yarmulke nestled atop his wavy salt-and-pepper hair.

Faten Nastas, 33, is a mother of three from the West Bank city of Bethlehem whose study permit request was rejected by the army in 2005. Ms Nastas, who completed a bachelor's degree in 1998 at Israel's prestigious Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, had been accepted by the institution to a master's in art, a programme that does not exist at West Bank universities. "It has messed up my plans and hopes," said Ms Nastas, who had aspired to gain more experience as an artist and is still battling for a permit with Gisha's help.

For Ms Salameh, the fight is far from over. Uncertainty looms over whether she will get to finish her doctorate and possibly become one of the few female science professors in the West Bank. "Unlike the other students at Hebrew University, I have to finish the degree very fast," she said with a sigh. "I'm afraid that if the political situation worsens, the army will take my permit away." @email:vbekker@thenational.ae