CAIRO // Two years ago, Omar Suleiman hurried out the doors of Egypt's intelligence headquarters to an armoured Mercedes 350 and a BMW X5 idling on a ramp reserved only for the vehicles of the country's most powerful men.

Instead of sliding into the back seat of the BMW, as he had planned, the former spy chief and newly appointed vice president absent-mindedly stepped into the Mercedes. The mistake probably saved his life.

Minutes after the two-car convoy rolled away from the spy agency in the Hadaeq Al Qobbah neighbourhood of Cairo, the BMW in which Suleiman was supposed to be riding was raked by a hail of automatic weapons fire, killing the driver and a security guard.

The brazen daylight attempt on the life of one of Egypt's most powerful men was quickly overtaken by other events during the tumultuous final days of the Mubarak regime. Since the January 30, 2011, attack, however, no government investigation has attempted to sort out the mystery of who might have wanted Suleiman dead and why.

A former National Democratic Party official, who declined to be named because of the sensitivity of the situation in Egypt, said the truth about the assassination plot may not emerge for years, since only a handful of people have knowledge about the machinations of Mubarak and his inner circle as his regime collapsed.

"This man was the vice president travelling in a highly secure zone," the former official said. "Only a few people on earth knew the route he would take and the time he would take it and the car he would be in. All of that tells me that it was a power struggle at the top."

There is little doubt that on the penultimate day of January in 2011, the public profile of the already powerful Suleiman was set to rise substantially.

A day before the attack, Mubarak had appointed Suleiman the vice president and given him the job of overseeing a sensitive "national dialogue" with opposition forces, a week into the biggest protests in the country's history. Hundreds had been killed in clashes with police and the momentum of the movement to topple the presidency was growing.

Poised to play a potentially pivotal role in the outcome of the uprising, Suleiman rose early on the morning of January 30 and headed to the presidential palace in the armoured Mercedes 350 to begin setting up meetings for the dialogue, according to two people to whom Suleiman later recounted the events of the day.

Later that morning, he left the palace and took the same car to the General Intelligence Service (GIS) headquarters to clear out his desk and consult with General Murad Mowafi, his replacement, about the transition. Before entering the headquarters building, he told his driver of 25 years, Zakaria, and personal bodyguard, Mohammed, that he would leave the Mercedes behind for Mr Mowafi's use. He would take his other car, a BMW X5.

At about 11am, a call came in from Mubarak's office: the president would like to see Suleiman in half an hour. In the sudden rush to return to the presidential palace, however, he stepped into the Mercedes instead of the BMW.

As both cars sped to the palace, past the Saray El Qobba Palace Gardens and onto Fangary Bridge, Suleiman asked Zakaria why the BMW was accompanying them. Reminded by the driver of his earlier request, Suleiman laughed. I guess I'm preoccupied, he said.

It was after a U-turn, when the cars were near the armed forces medical complex in Kobry El Qobba, that gunmen opened fired on the BMW. In the fusillade, the driver and security guard in the BMW were killed, and another guard was wounded. Several army officers at a nearby checkpoint wildly returned fire, killing one of the gunmen.

Suleiman asked to stop and check on the men in the accompanying car, but Mohammed, his bodyguard, insisted on moving the vice president to safety. He arrived at the palace at 11.30am.

The president opened an investigation into the incident, but it was later closed, according to a source who spoke to Suleiman about that day.

"The bodies vanished," the source said. "Omar never brought it up again. He only said 'God must love me because I got into the wrong car'."

News of the attempted assassination did not leak out for several days, but when several news organisations began issuing stories saying that Suleiman had survived a murder plot it was quickly denied by government officials.

A government statement issued on February 5 and quoted by the Associated Press said that a stray bullet from an exchange of fire between "criminal elements" had struck a car in Suleiman's motorcade as it moved through a restive area of the city. There was no evidence the vice president was intentionally targeted, it said, adding that the shooting was a random incident.

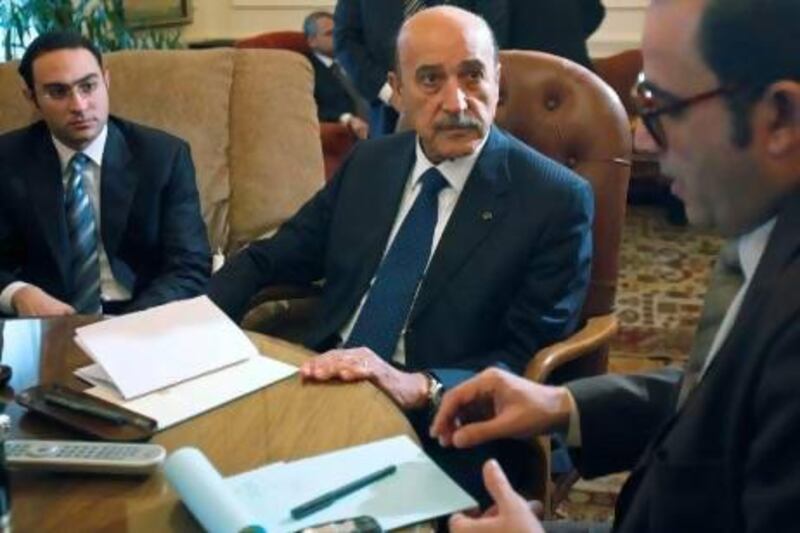

However, Ahmed Aboul Gheit, Mubarak's former foreign minister, recalls an unusually chastened Suleiman take unusual security precautions a day after the shooting.

Writing his recently published memoir, My Testimony, Mr Abou Gheit said he saw Suleiman entering from a side entrance rather than the main gate of the presidential palace. A member of the Republican Guard told him that Suleiman had been the target of an assassination attempt the previous day and was taking extra security precautions.

Speaking on the Al Hayat channel on February 24th, 2011, Mr Abou Gheit said that the attackers had fired from inside a "stolen ambulance".

Before he could publicly offer his own theory of who might have wanted to kill him on that late January day, Suleiman died on July 19, 2012, from complications arising from what his doctors believe was amyloidosis - a disorder caused by the build-up of abnormal proteins in tissues and organs.

Yet his death has not quieted speculation and conspiracy theories about the apparent assassination attempt.

Certainly, many people had a motive to want Suleiman dead. As a senior spy since 1986 and the head of the GIS since 1993, he presided over a crackdown on Islamic extremists. He also allowed the US to send men suspected of terrorism to Egypt, where many of them were tortured and kept in shadowy prisons for years without charges.

The assailants' detailed knowledge of Suleiman's itinerary and the car in which car he would be riding has also fuelled conjecture about the possible role of Gamal Mubarak, the son of the president who many argue stood the most to lose with Suleiman's rise.

Gamal was widely assumed to be preparing to run for the presidency later in 2011 and according to this theory, a newly promoted Suleiman stood in the way of fulfilling that ambition.

bhope@thenational.ae