The grainy footage, shot from the side of a dusty road in northern Syria, has been held up as a blunt metaphor for a historic shift in geopolitical power in the Middle East.

As a convoy of US troops speed along a highway leading from Kobane, they pass just metres from the Syrian army advancing to fill the void. The flags of the two armies flash by each other, neither side slowing even to acknowledge the other.

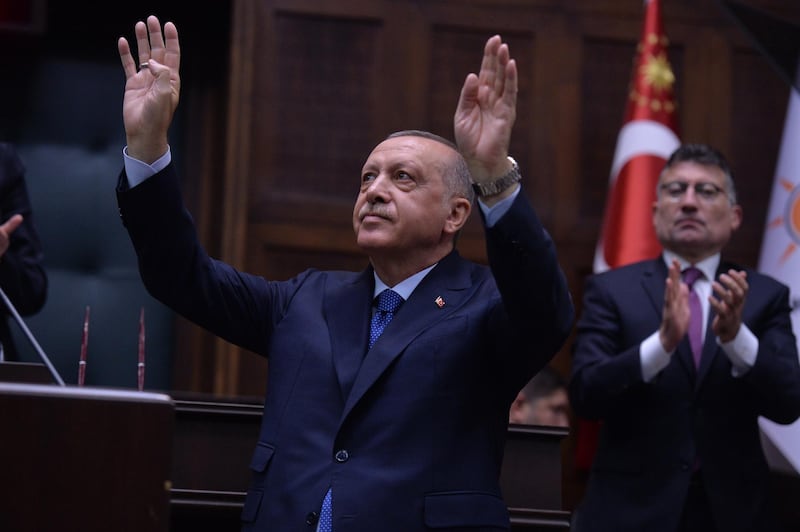

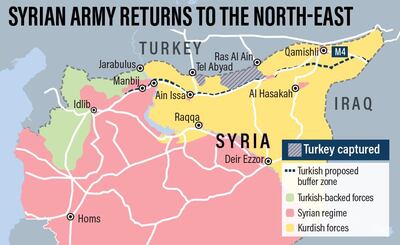

US President Donald Trump’s decision last Sunday to withdraw remaining American troops from northern Syria is being seen in Moscow as the final step in a long retreat from the Middle East. In America’s wake, they have exposed their Kurdish allies to an onslaught from advancing Turkish forces.

The move has left an unmistakable void, which Russia, Syria’s most important international ally, has steadily leveraged since the Kremlin rushed in to bolster the forces of Syrian President Bashar Al Assad in September 2015.

“The Kremlin must feel that it has finally returned to the world stage as a recognised force in international politics,” says Maxim Trudolyubov, Senior Fellow at the Kennan Institute.

Russia entered the Syrian conflict in 2015 with an unrelenting campaign of airstrikes that decimated armed opposition to the Syrian army and all but turned the tide of the war in Mr Al Assad’s favour.

In the years since, the Kremlin emerged as the primary political broker in the conflict, leading negotiations between some of President Al Assad’s main backers and opponents, Iran and Turkey.

The deal this week, in which Syrian Kurds who controlled the north allowed the regime to retake key towns in the north to stem a Turkish offensive, was brokered on Russia’s airbase in western Syrian.

But Moscow’s ability to win the trust of the big players in the Syrian conflict, Mr Trudolyubov wrote in a recent analysis, has played out across the region.

Russia, he says, has been successful in getting recognition for its efforts in the region from players as diverse as Iran, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Turkey.

“Most leaders of those countries may not want to sit down for a conversation between themselves, but each of them, separately from the others, is talking to Putin,” he said.

At the same time, since the war in Syria broke out in 2011, Washington has seen as having been an inconsistent and unpredictable backseat player.

In 2013, former US President Barack Obama’s failure to enforce Washington’s own “red lines” in Syria after Mr Al Assad’s chemical attack in Ghouta claimed hundreds of lives.

Confusion followed US President Donald Trump’s stalled decision to withdraw US forces from northern Syria in December last year.

Russian state-run media this week lashed out at the Kurds in northern Syria for having placed their trust in an unpredictable United States and not the Syrian President or Russia. Anchors and editors said both have been consistent in their objectives since the beginning of the conflict.

Dmitry Kiselev, the host of the major weekly talk show Vesti Nedeli, said on Sunday that, "the fate of the Kurds, of course, arouses sympathy. But, at the same time, you must understand that, for some reason, the Kurds in Syria chose America as their ally, and not the president of their country –Assad – and not Russia, which unfailingly helped to rid Syria of ISIS."

Mr Kiselev said that the United States has used the Kurds as “cannon fodder” and described Washington as having “betrayed and dumped” the Kurds.

“Yet again,” he added, “the Kurds made a mistake with their choice of protector. The US is not a reliable partner.”

The fact that the Kurds turned to the Assad regime in Damascus is being heralded a major win in Moscow for what analysts say has been the Kremlin’s consistent set of goals and policies set out since the intervention in Syria in September 2015.

“Russia’s influence in Syria has been again tested and proven strong as a result of the Kurdish decision to seek an alliance with Damascus,” Dmitry Trenin, the director in Moscow of the Carnegie think tank, said.

“Keeping contacts with all [players], including Turkey, and having a clear view of one’s own interests and thus a coherent policy is paying off.”

The question that remains to be seen is how long Russia can maintain friendly ties with leaders in a bitterly divided region.

Already, analysts in Moscow say there may be signs of wear.

“Here's a dilemma for Putin,” says Yury Barmin, a Middle East analyst at the Russia International Affairs Council think-tank, which was established to advise the Kremlin. “How to permanently cement the gap between the US and Turkey that emerged in the northeast [of Syria] while trying to get Erdogan to relinquish his ambitions in that region.”

The answer to this is likely to be the main occupation of many of Mr Putin’s foreign policy officials.