RISHON LEZION, ISRAEL // Khaled Shakra does not normally pretend to be Jewish.

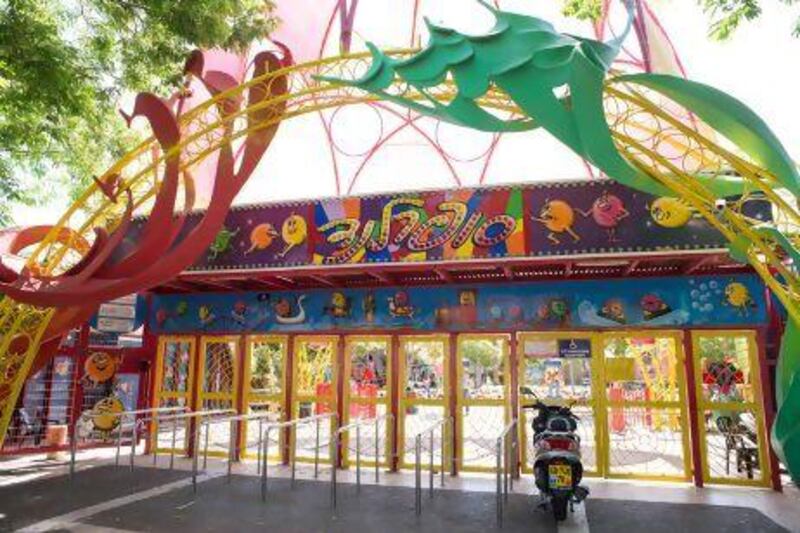

But when a popular amusement park in this city last month initially rejected the teacher's request to book a field trip for his grade-seven English class, he suspected discrimination.

So, using a common Jewish name, Eyal, and his impeccable Hebrew, he telephoned Superland park about an hour later. The same employee who fielded his previous call accepted his request to reserve a day of water rides and roller coasters for his class, he said.

Mr Shakra, an Israeli Arab, said his suspicion was confirmed.

But he said he felt more sad than surprised afterwards.

"This is just a small example of how we face this kind of discrimination on a regular basis," said Mr Shakra, 29, who teaches at the all-Arab Ajyal School in the nearby city of Jaffa. "We're talking about segregation, which is against the very principles of democracy."

Mr Shakra is one of Israel's 1.6 million Arabs, its largest minority of citizens who vote, speak Hebrew and can serve in parliament. They also have long decried institutionalised discrimination and racial tensions with Jews, including a recent spate of anti-Arab attacks that many have attributed to a rising nationalist-Jewish climate fostered by Israel's right-wing government.

The Superland incident signals what Mr Shakra and other Arab citizens fear has become a broader tolerance for racism in Israel. Despite laws that outlaw racial discrimination, it is not uncommon for restaurants to refuse service to Arabs and businesses to adopt a Jews-only hiring policy. Offhand and offensive remarks alluding to Arabs and Muslims as "backward" are also common.

On Tuesday, Israel's Channel 10 aired an investigation showing how the country's largest bank, Bank Hapoalim, refused to allow its Arab customers to transfer accounts from branches located in Arab areas to Jewish ones.

"This sort of behaviour is becoming completely internalised in society, and many people don't even recognise it," said Abir Kopty, a critic of Israeli policies and a former member of the city council in Nazareth, an Arab city in the Galilee. "If they do recognise it, many are just in denial."

After Mr Shakra posted his experience with Superland on Facebook, the media began reporting the incident and the park subsequently admitted that it segregated clientele between Jews and Arabs by not scheduling mixed groups on the same day

But in statements to the media, Superland also said the decision not to mix its customers came at the request of schools, which regularly hold end-of-year celebrations at amusement parks.

"The management of Superland had received requests, from Jewish and Arab schools alike, to conduct these events on separate days," the park said this week in the Israeli Haaretz newspaper.

The park added that it decided to hold separate days for Jews and Arabs because mixed outings could "lead to tension and violence".

Superland officials declined a request to be interviewed.

In Israel, Arabs and Jews already attend separate schools and interact relatively little in social settings.

But Superland's response drew some angry responses from Israeli officials. Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister, condemned Superland for "racism against Israeli Arabs".

Israel's defence minister, Moshe Yaalon, said he was "shocked and embarrassed" by Superland's decision, and Ahmed Tibi, an Arab member of parliament, even called for the amusement park to be closed.

Nadeem Shehadeh, an attorney at the Legal Centre for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, or Adalah, said the government may have grounds for forcing Superland to shut. Such segregation contravenes a law passed in 2000, which outlaws discrimination in public and private places.

He compared Superland's policy with the "separate-but-equal" legal doctrine that once separated blacks and whites in the United States.

Mr Shehadeh said his organisation had seen an increase in complaints about segregation at establishments across Israel. He referred to another recent incident in Rishon Le Zion in which an Arab was initially refused a reservation because the restaurant said it was booked for the evening.

"When he called two hours later and said he was Jewish, he got a place at the restaurant," Mr Shehadeh said.

He and But most such incidents go undocumented because, he said, Arabs believe that speaking up will not help.

He and Ms Kopty, the former council member, said this is partly because of the rising religious-nationalist sentiment among Jewish politicians that has helped to fuel racism, with several laws passed in recent years singling out non-Jews. These include loyalty oaths and committees that critics say allow communities to filter out potential Arab residents.

"Politicians always say they regret what's happening and that we are a democratic state, but what's happening at the government level is feeding what's going on in the street and legitimising racism," said Ms Kopty.

For Mr Shakra, he hopes his students - and Israeli society - can come to terms with what happened at Superland.

His experience left him certain about one thing, he said. "My students and I will never set foot in that place."