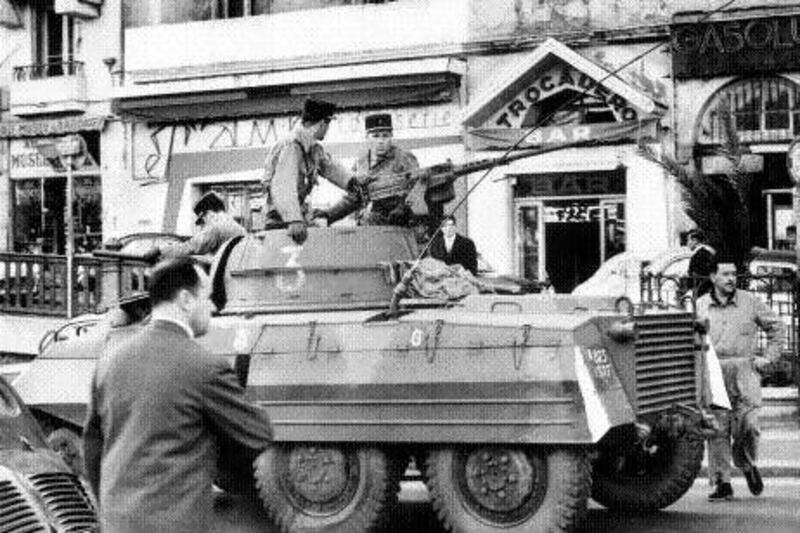

MARSEILLE // France was divided yesterday on its first day of national commemoration intended to honour the dead from conflicts in its former North African colonies.

Opponents of the initiative, mainly in the south of France, complained that treating March 19 as the date on which hostilities in the Algerian war of independence ended in 1962 overlooked the widespread bloodshed that continued for many months.

Families of the harkis, the Algerian Muslims who fought on France's side against the rebels of the National Liberation Front (FLN), and the so-called pieds-noirs, European settlers who fled to France, were particularly angered by the initiative.

The French parliament passed a law last December designating a "national day of remembrance and meditation in memory of civilian and military victims of the war in Algeria and conflict in Tunisia and Morocco".

March 19 was the date of ceasefires being announced 51 years ago, one day after the signing of the Evian accord that led to Algerian independence. It is already commemorated in street names in some French towns and cities.

The reference to Tunisia and Morocco in the new law reflects the violence in those countries, on a much lesser scale, before independence was granted in 1955 and 1956 respectively.

But Algeria is the focus of the dispute. Mayors opposed to the socialist president, Francois Hollande, and his government refused to recognise the occasion and protests have been held in several areas.

One mayor, in the southern town of Perpignan, registered his dismay by flying the French tricolour at half mast from the town hall. Others simply ignored official calls for ceremonies to be held.

The national commemoration can be seen as part of Mr Hollande's drive to improve relations with the countries of the Maghreb that France once ruled. Algeria is of special significance, as was evident recently when French fighters were allowed to use its airspace when attacking Islamist insurgents in northern Mali.

But the event has been overshadowed by a series of other anniversaries recalling the series of killings by a self-styled French-Algerian jihadist, Mohamed Merah, in March last year. He shot dead three Jewish children, the father of two of them and three soldiers in Toulouse and Montauban before being killed in a shoot-out with officers from a special police unit.

Controversy over yesterday's commemoration was stirred by Jean-Marc Pujol, the centre-right mayor of Perpignan, in an open a letter to Kader Arif, French secretary of state for former combatants. Mr Pujol is from a pied-noir family.

"It is out of the question that we can associate ourselves with these ceremonies," Mr Pujol told the Toulouse-based regional daily newspaper, La Dépêche du Midi.

He said the choice of date was a "falsification of history … a purely political measure the socialist government wishes to impose on us".

In his letter to the minister, himself the son of a harki, he wrote: "After March 19, the FLN's attacks continued and harkis abandoned by the French republic were massacred."

A communist councillor, Nicole Gaspon, expressed shock at his remarks, describing March 19 as a symbolic date signifying decolonisation and the loss of France's colonial empire.

"Fifty years later, the mayor is in denial," she said. "He wants to confiscate history for partisan purposes."

But Abdellah Krouk, president of France's National Federation of harkis and others repatriated from Algeria, condemns the law as an act of "memoricide". Quoted by another French newspaper, Midi Libre, he said the French government bore responsibility for the "genocide" of 150,000 harkis and their families after March 19.

Another opposition politician, Christian Estrosi, also refused to associate his city, Nice, with the ceremonies, defying regional officials' instructions that public buildings should be decorated to observe the commemoration. He said the post-independence conflict had caused the deaths of 60,000 harkis and 3,000 Europeans, as well as driving more than a million French people out of Algeria.

French politicians began the process of deciding on a national day of commemoration 11 years ago.

Previous attempts to establish a date foundered. At the instigation of a former French president, Jacques Chirac, December 5 is already designated a day of national homage to those who died "for France" in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. This date does not correspond to any specific anniversary in the timetable of independence.

The controversy has been presented in France as a north-south split because most of those fleeing Algeria after the war made their new lives in southern areas. Predictably, the far-right Front National of Marine Le Pen said it, too, would boycott the commemoration.

However, Guy Darmanin, director of the National Federation of Former Combatants in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, told France 24 television there was a republican duty to respect a law passed by parliament.

He argued there was a violent aftermath to all wars. "For the Second World War, we celebrate the armistice of May 8, whereas the war really ended in September after Hiroshima."

The Algerian media pointed out that the paramilitary French group, Secret Army Organisation, had continued bombings and assassinations despite independence. Le Temps d'Algerie quoted a former FLN commander, Rabah Zerari, as describing March 19 as a date ending a long, harsh winter of colonialism and "opening the doors of spring for Algeria".

[ foreign.desk@thenational.ae ]

twitter: For breaking news from the Gulf, the Middle East and around the globe follow The National World. Follow us