BENGHAZI, LIBYA // With its pretty Italian-style buildings, tropical palm trees, proximity to substantial oil reserves and direct sea access, Benghazi should be both picturesque and prosperous.

It mouldered for decades under the rule of Muammar Qaddafi, but in the euphoric days after the despot's fall last year there was hope that Libya's second city would at last enjoy international investment and development, and better hospitals and schools.

"Things were excellent after the revolution," says Naem Al Buri, a member of a business union that now welcomes frequent delegations from European countries. "The market was getting bigger, and we were looking to the future."

That optimism was shattered last week by a few hours of bloody violence that killed the US Ambassador J Christopher Stevens and three other Americans. The attack on the US consulate exposed the weakness of the city's security forces and the ferocity of its extremist fringe, and left Benghazi citizens dreading a violent and isolated future, much like its past as a neglected sibling of Tripoli.

Officials tell of patient diplomacy, entreating ambassadors to open consulates, but as foreigners leave and projects are suspended they worry their work is in vain.

Twenty Italian companies due to arrive in Benghazi on Sunday needed some coaxing to go ahead with their long-planned visit. "After what happened, we are all worried," said Mr Al Buri. "We want foreign companies to come here. We want the city to be refreshed … Libya is backwards. We want to catch up with the world."

Residents also seem fearful of more violence in the city. Libyan and US officials have given different accounts of the attack - with debate centring on whether it was planned or spontaneous, independent or discussed with Al Qaeda movements. But at least some aspects of it were certainly conducted by well-organised armed men.

Although the number of militants seems to be small, security forces have been unable to thwart violent groups who have attacked British diplomats and a UN convoy in the months after Qaddafi's death last October.

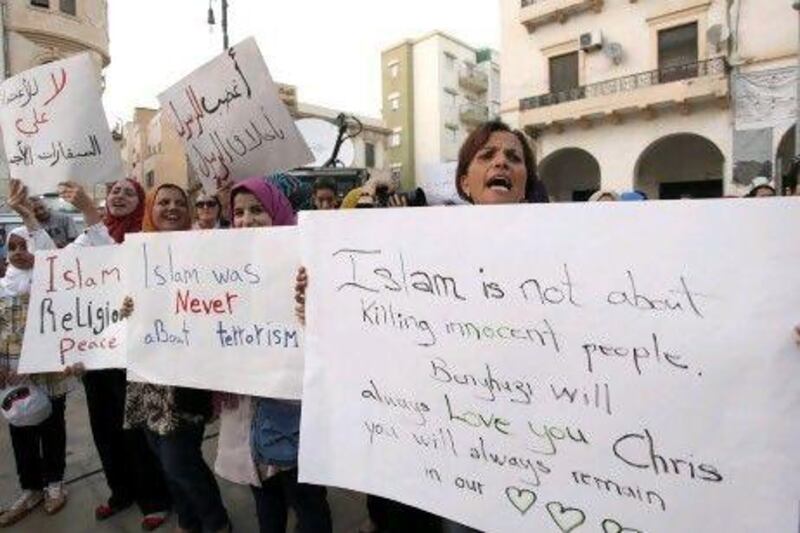

There have been only minor protests here against the film that sparked regional chaos, and extremists seem to represent the attitude of few people.

On streets and in mosques, many expressed horror that people they saw as honoured guests were killed in Benghazi. "We feel so sorry," said Mohammed Hussein, a 23-year-old student. "We don't want this even if they talked about the Prophet and Islam, it is going to bring bad luck."

The perpetrators of the attack on the US consulate had long beards, cried "God is Greatest" and waved the black flag used by extremist groups, but some members of the city's community of ultrareligious Salafi Muslims vehemently distanced themselves from the violence.

"Attacking the ambassador is totally condemned," said Akram Al Dressi, an imam, in his Friday sermon at a mosque where most worshippers are Salafists. "The Prophet said killing the pure spirit or soul is forbidden in Islam." Besides the theological argument against such activities, he said such actions would bring "tragic events".

"We don't want to end up like Iraq," he said, reflecting a widespread worry that Benghazi's armed groups could fight one another and that the United States may seek retribution. American drones now criss-cross the city's skies, making people nervous. In an interview later, the imam estimated the number of people in the city he would call takfiri - those who declare other Muslims to be unbelievers and support violence - at a maximum of 2,000.

The imam and others identified places where militant Islamists pray and named some of their religious leaders, including one known as Sheikh Abu Khatela. Two security officials - Wanis Al Sharif of the interior ministry and Fawzi Wanis of the Supreme Security Council - said a number of members of the extreme Islamist Ansar Al Sharia militia were present at the burning of the consulate.

But neither said the group would face difficulty from the security forces. Ansar Al Sharia denies involvement nor was there any sign of concern among members of the group, who gave a press conference denying responsibility for the attack.

However, Mr Al Sharif and the head of national security for Benghazi, Hussein Bou Hmida, were both sacked by the interior ministry.

In Benghazi, many express fear and disdain when asked about the group. "They are the dogs of hell," said one man - but they have little faith in security forces' ability to curb their excesses.

"In all of Libya, there are no more than 5,000," said Mr Al Dressi, the imam. "But their evil is more than they are - if security forces arrest some of them, they can do crazy things."

Mr Wanis of the Supreme Security Council wearily explained the problems of keeping Benghazi safe. He now has 18,000 men, mostly members of rebel brigades who fought during the uprising against Qaddafi last year. Libya's government has struggled to bring these well-armed groups under control and Mr Wanis said that there are "good and bad" men among them.

"We have more than 300 institutions to protect," he said. "It is too much."

So overwhelmed are his patchy forces that he recently succumbed to pressure from Ansar Al Sharia, who had declined on principle to become part of the security force. He allowed the group to take over the security of Al Jalla hospital, where gunmen had frequently shot up wards.

In the hospital, a shabby place with peeling posters on the walls and a half-dozen bearded gunmen snoozing in a courtyard, the staff conceded that the group had improved security, but did not pretend to like them.

"They have no legitimacy … but we resorted to something that solves our problems," said Mohammed Al Gharouby, head of public affairs at the hospital, while Brika Al Qaddafi, a supervisor and nurse, complained that the men harass women and want them to wear full-face veils. The guards declined to be interviewed.

For now, life goes on in Benghazi with little more disruption than usual. At night, there are still occasional rattles of gunfire, but a doctor in the town's largest hospital said instances of gunshot wounds have fallen substantially since the beginning of the year when fights between militias were common. Children play in the evening along the shorefront, the universities and schools will reopen soon.

But those who could undo all the post-revolutionary progress and optimism move about a city without checkpoints with impunity. On Friday, a few dozen men with long beards and black banners staged a demonstration outside the Tibesti hotel.

One, Mohammed Al Miffi, detailed his involvement in the torching of the consulate within easy earshot of members of the security forces and television cameras. He said he had helped to organise the protest in the place of maximum visibility.

He held a large sign reading: "They curse our Prophet, nobody moved, but an American dies, and the world is upside down."