The August 4 blast in Beirut did not kill Hadi Succar immediately. He was asleep in bed when the huge explosion ripped through Beirut and the shockwave shattered the windows next to him.

Liliane Succar, 60, says she knew something was wrong when she saw the glass lodged in her husband’s eyes.

Overworked doctors rushing to treat those wounded in the explosion discharged retired lawyer, 76, with a packet of Panadol and some antibiotics, telling him to book an appointment with an ophthalmologist.

But about 7am on August 8, Succar collapsed at breakfast in his stepmother’s home where the couple were staying after their house was destroyed.

An hour later, medics at the hospital pronounced him dead from a heart attack.

"He was traumatised and diabetic," Mrs Succar tells The National. "It wasn't just an explosion. It was the most horrible sound I ever heard in my life."

A month after 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate stored at Beirut port exploded, killing at least 190, injuring 6,500 and leaving 300,000 people homeless, Lebanon is still reeling from the shock of one of the biggest non-nuclear blasts in history.

“I am so unwell. I can’t sleep,” Mrs Succar says. “My life has been turned upside down.”

The aftermath of Beirut blast

The city is starting to rebuild but the damage is visible everywhere.

Rescue teams are still combing the rubble, military engineers are still going door to door to assess damage to homes and many who fled the devastation are yet to return.

On Thursday, a team of Chilean rescue workers detected two bodies under the rubble of a house in Beirut's Gemmayzeh.

Hopes were raised after they said there might be signs of a pulse and breathing 28 days after the blast.

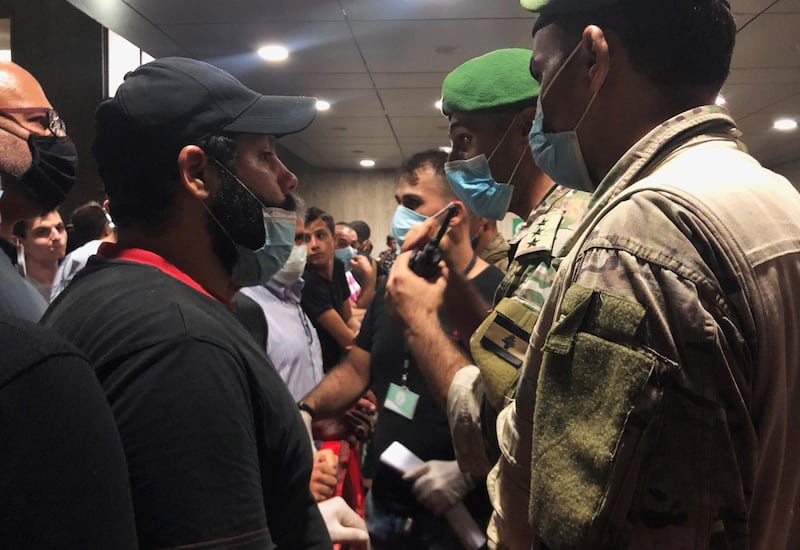

Lebanese Civil Defence and the army arrived on the scene and rescue workers dug through the evening as a crowd gathered on the street.

The eight-month-old government resigned after the blast, but no politician has apologised and the local investigation has yet to pinpoint responsibility for the disaster.

Three people are still missing.

On Monday, political parties agreed to nominate Mustapha Adib, a little-known former ambassador to Germany, as Lebanon’s next prime minister. But few believe he will be able to fix Lebanon’s problems.

The task is huge and the Lebanese have lost faith in their leaders.

Long before the blast or the coronavirus pandemic, the small country was already suffering from its worst economic crisis and defaulted on debt for the first time.

Unlike in decades past when foreign backers and friends readily handed financial lifelines to bail the Lebanon out, external help this time is contingent on deep structural reforms.

Since last October, politicians have also been faced with hundreds of thousands of angry people tired of years of inaction, poor governance, corruption and non-existent public services on the streets of towns and villages from the north to the south.

Since then, the local currency has lost about 80 per cent of its value on the black market. Half of the Lebanese now live under the poverty line and the number is increasing.

Emergency aid poured in from overseas after the blast. The UN said on Thursday that it raised $56.4 million (Dh207.1m) since August 14, but very little has been handed to the government.

There have been persistent rumours that humanitarian aid not channelled through the UN has been misused or disappeared.

French President Emmanuel Macron touched on the issue on Monday during his second visit to the Lebanese capital since the blast.

Mr Adib knows that the task before him is difficult, Mr Macron said.

“He is lucid," the French leader said. "He went in the streets last night.

"Clearly, he knows that he not seen as a saviour, not because of who he is but because he is the result of decisions of political parties who do not have the trust of the people."

Mr Adib can only gain legitimacy by forming a government within 15 days, Mr Macron said.

Lebanese political parties promised the French president that this would be the case.

Most administrations in the past 30 years have taken between five and 11 months to be formed, Mr Macron said.

In the meantime, people on the streets of Lebanon continue to help each other to rebuild, restore and return to some sense of normality.

But for many, the scars left by the blast run deep.