The Iraqi commander named in an arrest warrant for killing of dozens of demonstrators in recent days is the product of a system of repression harking back to Saddam Hussein’s rule, when competence was measured by the brutality meted out.

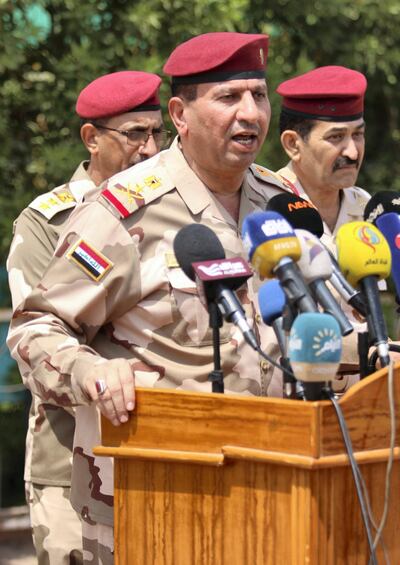

But General Jamil Al Shammari is only one among a group of senior enforcers in the Iraqi army and security apparatus whose career has been marked by violence against civilians.

Iraq’s Higher Judicial Council said that Sunday’s arrest warrant against Gen Al Shammari was for “the crime of issuing orders that caused the killing of demonstrators” last week in the southern city of Nasiriyah, capital of Dhi Qar Governorate.

Magistrates in Dhi Qar issued the warrant that bars Gen Al Shammari from leaving the country, but he has not been detained since the indictment was announced.

Several Iraqi sources said they have to be careful when talking about the case, with Gen. Al Shammari backed by Iran and amid the disappearance of dozens of campaigners and activists.

But the officer the most prominent figure to be indicted since the beginning of the suppression of the continuing uprising, which has left more than 400 protesters dead and thousands wounded since October 1.

Gen Al Shammari was in charge of Nasiriyah when dozens of demonstrators were killed last Thursday in what became known in Iraqi media as the Nasiriyah massacre.The killings by government forces prompted the resignation of Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi, himself a native of Nasiriyah, a day later.

David Schenker, US assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs, said on Monday that “use of excessive force” in Nasiriyah “was shocking and abhorrent” and that the Iraqi government “must investigate and hold accountable those who attempt to brutally silence peaceful protesters.”

But it isn’t the first time Gen Shammari has been dispatched to quell demonstrations in the predominantly Shiite south.

In 2018, Gen Al Shammari was the military commander in charge of Basra when troops killed dozens of Shiite demonstrations.

The former prime minister Haider Al Abadi ordered Gen Al Shammari back to Baghdad but instead of facing an investigation he was appointed to head the country’s military college.

Gen Shammari is a stocky man in his early 50s. He is among a generation of Iraqi Shiite officers who rose swiftly in the ranks after the 2003 US-led invasion.

The past 16 years of Shiite domination has replaced the Saddam-era Sunni monopoly in state bodies.

But in the fracturing sectarian landscape of the country, a campaign backed by the Najaf clerical establishment against Sunni militants in 2005 produced Shiite militias and death squads, contributing to a civil war that largely ended with the recapture of the city of Mosul from ISIS in 2017.

Imad Al Khafaji, an Iraqi political commentator, said Gen Al Shammari is among a group of Shiite officers of similar age sent from Baghdad to the south over the past year to pacify a Shiite population whose discontent exploded in October.

After the burning of the Iranian consulate in Najaf last week, triggering demands from Tehran for serious action, Mr Abdul Mahdi ordered military commanders to restore control.

And therefore, Gen Al Shammari was again on the scene when security forces caused the deaths of dozens of civilians.

On October 28, at least 29 people were killed when soldiers fired on protesters in Nasiriyah leading powerful local tribes to threaten open rebellion.

While there is no official confirmation of Gen Al Shammari’s involvement in the crackdown in Nasiriyah last week, it is for this operation that the arrest warrant was issued.

As the bloodshed in Nasiriyah unfolded, Gen Al Shammari was recalled to Baghdad.

Mr Al Khafaji said that even with Gen Al Shammari’s departure from Nasiriyah, several of his high-ranking colleagues have remained in the south to oversee the security response. Rather than being an exception in Iraq, Gen Al Shammari is – he said – indicative of a broader mentality in the armed forces.

"We have a military that believes that when an order is given you have a right to use every possible means for repression," Mr Al Khafaji told The National. "Shammari should not be absolved, neither those higher up who had sent him to Nasiriyah."

Mr Al Khafaji said that if the general ever appears before a judge, he could say he was following orders and implicate those that sent him south, including Mr Abdul Mahdi and the army command. In Iraq, political interference in the judicial system has endured long after the removal of Saddam.

One Shiite cleric said Gen Shammari was unlikely to face trial because he is well connected in the military and his brother, Abdul Amir Al Shammari, is a general in the army.

“Abdul Amir does not have the horrible reputation his brother has,” the source said. “Still he is unlikely to side against him”.

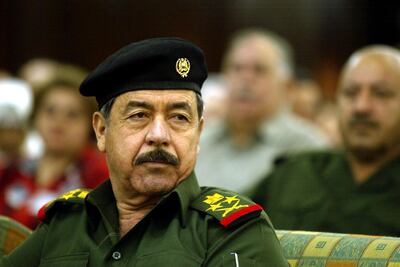

Violent means have been used to pacify Iraqis for decades, with total impunity under Saddam and with scarcely more rules in the years since.

But, political cover doesn’t always last.

Because of the US invasion, names that once projected invincibility by virtue of their association with Saddam have been tried and executed.

Among them was Saddam’s cousin, Ali Hasan Al Majid, nicknamed Chemical Ali for using mustard gas to carry out the 1988 Halabja massacre.

Another is Taha Yassin Ramadan, the former Iraqi vice president who plotted against Saddam’s rivals in the 1970s. Izzat Ibrahim Al Douri, vice chairman of Saddam’s Revolutionary Command Council, remains on the run.

While Gen Al Shammari is a rare case in the post-Saddam era of a top military figure coming under pressure for his methods, demands for accountability remain at the core of the uprising.

Mr Al Khafaji said: “The young people in the streets are not looking to repeat a system that their parents and grandparents have suffered from.”