BEIRUT // The threat posed by ISIL has seen historic enemies fighting on the same side. The United States battles the same enemy as Shiite militias that once laid improvised explosive devices along paths patrolled by American troops. Kurds warily fight alongside Arabs they accuse of trying to perpetrate genocide against them in the past.

In Lebanon, the country’s normally factious political parties agree on the urgent need to fight ISIL and Jabhat Al Nusra forces building up on the country’s eastern border with Syria.

Yet, the accord only goes so far. Exactly how to protect Lebanon is a matter of contention. The country remains deeply divided between those who support the uprising against Bashar Al Assad, and those who still back the Syrian president.

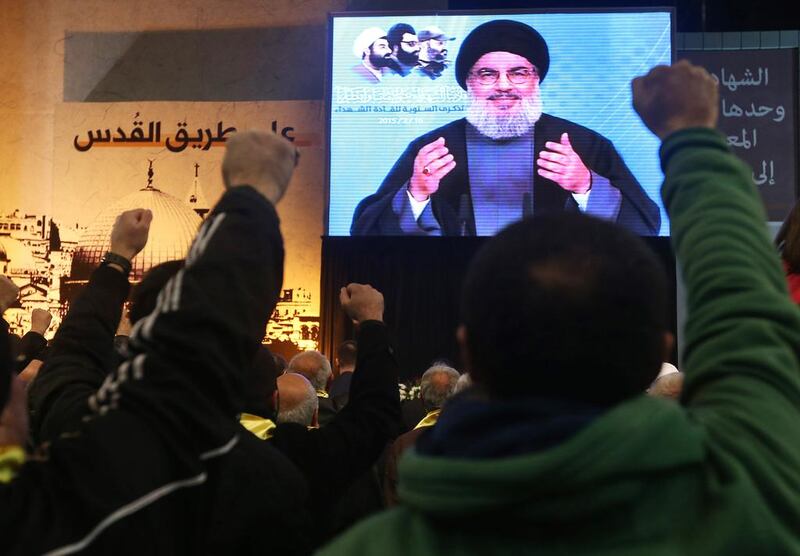

In a speech on Monday, Hizbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah — a supporter of Mr Al Assad — warned that when the snow melts on Lebanon’s mountainous eastern frontier and ISIL and Jabhat Al Nusra forces can move easier, Lebanon will have to figure out a way to protect itself from stepped up attacks.

To protect the border, the leader of the Iranian-backed militant group called on Lebanon to coordinate with the Syrian army, a force many here despise for its long, heavy-handed occupation of their country.

The frontier is currently manned by the Lebanese army — which battles attackers infiltrators on a near daily basis — along with Hizbollah forces. The group is also fighting inside Syria and Iraq, an intervention Mr Nasrallah has defended as necessary to safeguard the country from the threat of extremists.

“I call for those who are urging us to withdraw from Syria to join us in our fight in Syria,” Mr Nasrallah said. “Let’s go to Iraq and everywhere to face off this threat because this is the right way to defend Lebanon.”

This defence strategy does not sit well with Hizbollah’s domestic opponents.

While Hizbollah says its fights in foreign countries are about keeping Lebanon safe, their detractors blame those interventions for inviting the region’s wars to Lebanon.

“Withdraw from Syria. Stop dragging the fires from Syria to our country,” said Saad Hariri, the figurehead of the anti-Syrian government, anti-Hizbollah March 14 coalition in a speech last week.

Mr Hariri spoke at the 10th anniversary of the assassination of his father, former prime minister Rafik Hariri. An international tribunal has charged five Hizbollah members with involvement in the former premier’s Valentine’s Day death in 2005.

“The main thing for the March 14 group is that the intervention of Hizbollah is what led those radicals to target Lebanon’s borders and try to have access to Lebanese soil,” said Mario Abou Zeid, an analyst with the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. To March 14, “if Hizbollah would withdraw from the Syrian conflict and the Lebanese Armed Forces would assume its responsibility to protect the borders, things would change,” he added.

Lebanon falls within the area ISIL claims for its caliphate. Extremists have also carried out bombings in the country in revenge for Hizbollah’s role in Syria.

Lebanon's army of 65,000 is a force that often sits on the sidelines of the country's delicate sectarian conflicts, afraid of disintegrating as it did during the country's civil war and too weak to maintain control in many areas. The military has received increased military aid from the US and UK since ISIL appeared on the border and is waiting on the delivery of US$3 billion (Dh11bn) in French arms purchased with money from Saudi Arabia.

But despite the will to fight and the bolstered armouries, some still doubt the army’s capabilities to confront an assault from a group that has embarrassed much stronger military powers in the region such as the Iraqi Army.

“The people inside March 14 know very well that if it wasn’t for Hizbollah intervening inside Syria, we would be fighting ISIL inside Beirut,” said Kamel Wazne, a Lebanese political analyst and founder of the Centre for American Strategic Studies in Beirut.

But American University of Beirut political science professor Hilal Khashan said it is important to remember that Hizbollah is “fighting all shades of the Syrian opposition” and is battling ISIL and Jabhat Al Nusra for its own agenda, reasons “unrelated to what other Lebanese factions may want.”

Hizbollah has been active in the Syrian civil war for several years now, entering the conflict initially to help the government fend off the Free Syrian Army. That move enraged many Sunnis in Lebanon and sparked unrest.

Late last year, Hizbollah and the Future Movement, the Sunni-backed political party that Mr Hariri also heads, began a series of reconciliation talks aimed at quieting inflamed sectarian tensions.

There has been some progress: Earlier this month, the sides struck an agreement to take down provocative political posters in Beirut and other Lebanese cities. A national antiterror strategy is being discussed by the two parties, but reconciliation remains elusive and hostility continues.

“The aim of these negotiations is to manage the conflict in Lebanon, not to solve the conflict in Lebanon,” said Mr Khashan.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae