BEIRUT// After Lebanon’s parliament failed to elect a president for the 33rd time, it seemed as though Sleiman Franjieh’s chances at winning the job had dimmed.

This was despite previous cautious expectations that a consensus had formed around him.

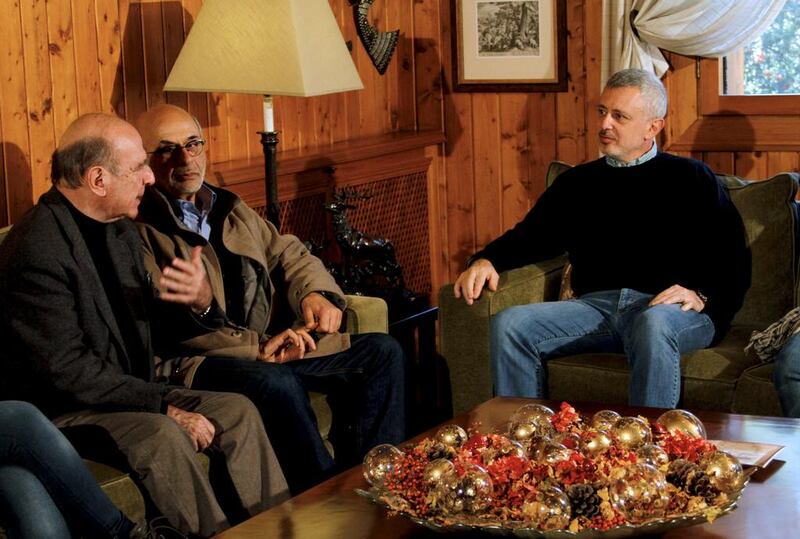

But the controversial politician, who is a close friend of Syrian president Bashar Al Assad, showed resilience late on Thursday, formally announcing his candidacy for the presidency just a day after the failed vote in parliament.

For weeks, Beirut had been abuzz with talk of a plan that would see Mr Franjieh, a 50-year-old Maronite Christian, become president and former prime minister Saad Hariri return to power.

Though various politicians and groups had publicly voiced their support for the plan, however, before Thursday Mr Franjieh had remained silent on the subject.

With Mr Hariri a Sunni whose Future Movement party leads Lebanon’s anti-Syria alliance, such a plan would represent a major attempt at rapprochement between Lebanon’s main political blocks, which are split over support or opposition to Syria’s government. If successful, it would end the country’s 18-month-long presidential vacuum.

By an unwritten agreement made at the outset of Lebanon’s independence in 1943, the president must be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni and the speaker of parliament a Shiite. The agreement was designed to ensure that none of the country’s sects can dominate the government.

But Mr Franjieh faces stiff opposition from two other Christian leaders who have their eyes on the vacant presidential palace. One is Samir Geagea, the leader of the Lebanese Forces, who is believed to have commanded a brutal 1978 attack on the Franjieh family mansion that saw Mr Franjieh’s parents and baby sister slaughtered. The other is Michel Aoun, an 80-year-old former warlord whose Free Patriotic Movement, as an ally of Hizbollah, is technically on the same side as Mr Franjieh.

Much of what Mr Franjieh said on Thursday seemed to be aimed at assuaging fears that his aspirations were threatening the cohesion of the Hizbollah-led pro-Syria political alliance, known as March 8.

“Today more than ever before, I consider myself a presidential candidate,” he said, according to Lebanese media. “But I will let General Aoun take his chance,” he added, announcing his candidacy on a Lebanese talk show.

“If Gen Aoun does not have a plan B, Hizbollah has a plan B. But this does not mean abandoning Aoun,” he said. “We are waiting and we will not sidestep Hizbollah or Gen Aoun. We have said from the beginning that if Aoun had a chance, we will be with him.”

Despite the portrayal of his candidacy as a backup plan, Mr Franjieh called his relationship with the general “abnormal” as of late and said that he would go ahead with plotting his own bid. He also said that his candidacy had been coordinated with Hizbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah.

Mr Franjieh’s bid has raised fears of splits within the March 8 alliance as it has appeared to turn Hizbollah’s two Christian allies into rivals. Gen Aoun is in a marriage of convenience, rather than an ideological alliance with Hizbollah and has been seen as willing to secure the presidency and power for his party at all costs.

Gen Aoun has spent much of this year trying to build up the power and support that would allow him to be installed as president. But so far, his spirited attempts have failed.

His supporters have staged a number of protests, at times violent, criticising Lebanon's lawmakers for failing to prioritise the selection of a new president. All the while, Gen Aoun has been instrumental in blocking parliament's attempts to elect a new president.

To be elected president, a candidate must secure a two-thirds majority vote in the 128-seat parliament. If no candidate can secure two-thirds, a candidate needs only a simple majority to win in a second round.

In the initial round of voting in April of last year, Mr Geagea led with 48 votes. But since then, MPs from Gen Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement and Hizbollah have boycotted parliament sessions aimed at finding a president, stalling a second vote as the former warlord jockeyed for power.

On Wednesday, parliament attempted to meet to elect a president, but as in previous attempts, the session was adjourned as there were not enough MPs in attendance to meet quorum.

For all three major candidates, deal-making across the political divide seems to be the only legitimate way to win the presidency.

But while Mr Franjieh’s election would represent a major breakthrough for Lebanon’s divided political parties, his pro-Syria stance could stoke dissent.

Since the conflict in neighbouring Syria began nearly five years ago, Lebanon has pursued a policy of disassociation, well aware of the strong emotions its neighbour stirs here.

Syria occupied parts of Lebanon from 1976 to 2005 and its troops were only forced out of the country after mass protests following the assassination of former prime minister Rafik Hariri, Saad Hariri’s father. Today, the Syrian government is either adored or hated by Lebanese, depending on whose side they are on.

Despite the policy of disassociation, Lebanon’s government has at times been accused of supporting the Syrian government, most notably by segments of the Sunni community.

Pro-rebel Sunnis have been angered by the Lebanese military allowing Hizbollah to operate freely along the Lebanon-Syria border, and aid the Syrian government.

Militant Sunnis have also battled Syria’s allies in Lebanon at times over the course of the war and crossed over the border to join the ranks of rebel and extremist groups.

In his interview on Thursday, Mr Franjieh did not shy away from his support for Syria’s government and his friendship with Mr Al Assad.

“I will not allow anyone to interfere in my relations with president Assad,” he said. “President Assad will not demand from me anything against Lebanon.”

Asked about his platform, Mr Franjieh chose a less divisive topic: Building the country’s broken infrastructure and ailing economy.

“I no longer want to dream of Lebanon in a political way. I want to dream of Lebanon with 24/7 electricity, with employment opportunities, that seeks investors,” he said.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae