A UK counter-terror watchdog has cast doubt on the effectiveness of a new measure to prosecute British extremists who travel abroad to fight for ISIS.

New powers were introduced in February that could see Britons jailed for up to ten years if they travelled to designated “no go zones” where extremists operated with impunity.

But Jonathan Hall, the UK’s new independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, warned that the new law could lead to undesirable unintended consequences.

He told The National that he had been contacted by charities worried that they could be criminalised for working in some of the most dangerous areas of the world.

He said that banks might be wary of allowing Britons to send money to their families in so-called terrorist hotspots because of fears of breaking the law.

“For what it is worth, I suspect that designating an area will be more relevant in terms of deterrence than in terms of prosecution,” Mr Hall said in his first speech since taking the job earlier this year.

The measure was introduced into law because of the difficulty of gathering battlefield evidence about the role of foreign fighters and made it easier to prosecute on their return home.

More than 900 Britons are believed to have travelled to Iraq and Syria to join the ranks of ISIS. Britain, like other EU nations, faces difficult decisions on what to do with the surviving fighters if they chose to return to the UK.

The new law on designated terrorist zones does not apply to people travelling to those countries for funerals, to care for terminally-ill relatives, or for certain professions, including UN and humanitarian workers, government staff and journalists.

The former interior minister, Sajid Javid, put Britons “on notice” in May when he said that he was looking at using the power in Syria with a particular focus on Idlib and the north-east of the country.

He also raised the prospect of using it in parts of west Africa where there has been a resurgence in Al Qaida affiliates and a continuing fighting involving the Boko Haram group.

But the measure has not yet been put in place amid doubts about its potential effectiveness after battlefield losses by ISIS has seen it lose control of territory and reverted to traditional terrorist activities.

The law would not apply retrospectively to any Briton who travelled to Syria to fight but cannot be prosecuted because of a lack of evidence.

Mr Hall questioned whether the new law would make it easier to prosecute given that it was already an offence to travel abroad to fight. Many people also remain beyond the reach of British law enforcement by remaining in the region.

“It is not possible to evaluate the efficacy of the power until it has been exercised but it is clear that any decision to designate an area requires shrewd judgment,” he said in a speech at the Royal United Services Institute in London.

“But what signals will designating a particular area as a terrorist hotspot send to the international community?

“What message would it send to the government of that country, or to allies who may have a different view about the threat posed by that territory? What if things are in a state of flux and shift decisively on the ground?”

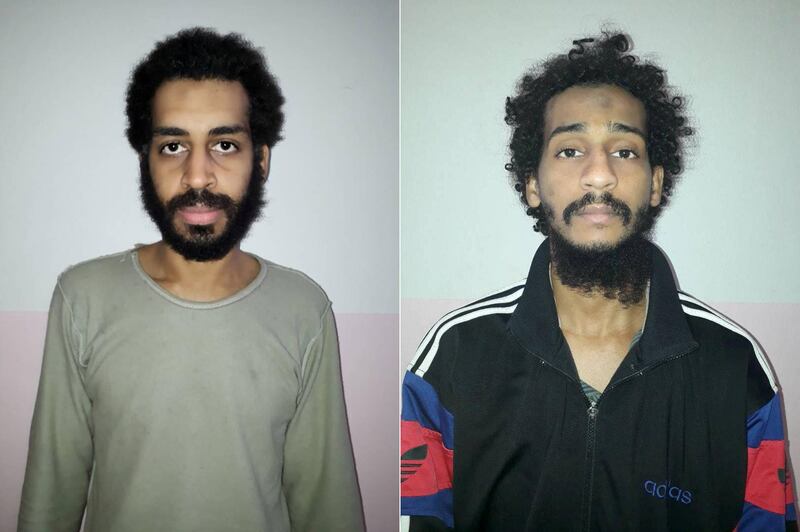

The new legislation comes as Britain seeks to outsource to the US the trials of two of its most notorious extremists, Alexanda Kotey and El Shafee Elsheikh, who are accused of being part of an ISIS assassination squad dubbed the Beatles.

They have been implicated in the murders of three US and two British citizens but UK prosecutors said they were unlikely to secure a successful conviction because of their treatment while being held in custody.