MARSEILLE, FRANCE // Three days before France chooses its next president, Nicolas Sarkozy is running a race against time to overtake François Hollande and prevent the left from winning its first presidential election since 1988.

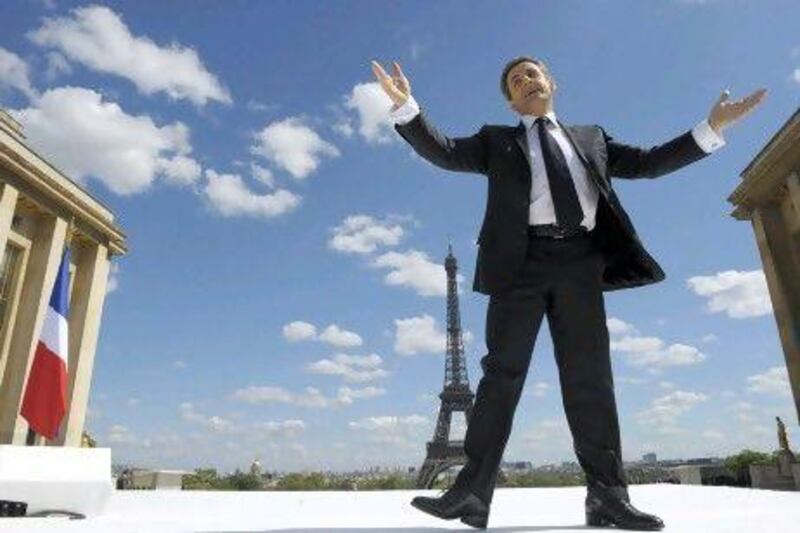

Deeply unpopular as the campaign began, after five turbulent years fighting the impact of the world economic crisis, Mr Sarkozy is outwardly confident he can pull off an extraordinary comeback.

Last night, as the two candidates prepared for a televised debate, the latest poll had Mr Hollande comfortably ahead in declared voting intentions for Sunday's second-round decider, as he has been throughout the campaign.

But Mr Sarkozy's pugnacity has helped him cut the lead, if only fractionally, to keep open the slender hope that a big turnout and a late shift in voting intentions may yet produce a surprise result.

Even some of his natural political allies have confided the belief that the president is "cooked". And Mr Hollande certainly strikes a triumphant note, claiming at a May Day rally that the French people had already said "au revoir" to the president. One poll reported yesterday, in which the president had clawed back a point against Mr Hollande, still gave the socialist a seven-point lead.

Much may depend on the redistribution on Sunday of the 18 per cent of first-round votes for the far-right Front National (FN) leader, Marine Le Pen.

Ms Le Pen told her supporters in her own May Day gathering, paying homage to the historical French heroine Joan of Arc, she would submit a blank ballot.

It came as little surprise that she withheld even grudging endorsement from either candidate since she has steadfastly presented her nationalist party as a credible alternative force in French politics.

However, she left it to supporters to act according to their conscience. With more than six million votes at stake, the mathematical implications are intriguing.

In collaboration with the polling institute Fondapol, the magazine of the pro-Sarkozy newspaper, Le Figaro, offered strikingly different outcomes.

In the first permutation, the share of the Le Pen vote going to Mr Sarkozy was 60 per cent with 22 per cent abstaining. With the smaller band of centrist voters evenly divided, the projected result gave Mr Hollande 53.1 per cent, a lead of just over 6 per cent - a simple majority being sufficent for victory.

But the second calculation had Mr Sarkozy's entreaties to the far right working to the extent that his share of the Le Pen vote rose to 72 per cent. Add a much bigger proportion of the centrist François Bayrou's support and he gains the slimmest of majorities, 50.1 per cent against 49.9.

Mr Bayrou will make his own declaration today, after having assessed the two contenders in their television debate. He may be in a minority; political analysts stress that France has no great tradition of being swayed by such gladiatorial skirmishes.

Mr Sarkozy's hopes may therefore rest on a combination of attracting Ms Le Pen and Mr Bayrou's voters in large numbers, overcoming the reticence of disgruntled supporters of his own UMP party and striking last-minute fear of the unknown into wavering hearts.

For all of Mr Hollande's calm authority and desire, he has never held government office despite long service in regional and party politics. Mr Sarkozy has portrayed his tax-and-spend plans as a recipe for higher unemployment and dwindling international confidence.

But controversy over Mr Sarkozy's attempts to attract FN voters shows every sign of continuing to polling day.

His defence minister, Gérard Longuet, suggested this week the centre-right could now work with the party, such was the difference between Ms Le Pen and her father, Jean-Marie, the former FN leader who was generally considered more extreme.

The foreign minister, Alain Juppe, retorted on Europe 1 radio that Mr Longuet was speaking for no one but himself. He welcomed the president's earlier assertion that there would be no deal with the FN and no ministerial posts.

Mr Sarkozy could have done without either intervention. He has already been criticised by opponents for adopting "collaborationist" language, an evocative charge in a country that still feels unease about the Second World War.

He has also had to deal with allegations from the news website Mediapart that Libya's Qaddafi regime agreed to contribute €50 million (Dh241.48m) to his 2007 presidential campaign. Mr Sarkozy denounces the report as false and intends to sue.

With Mr Hollande assured of support from the vast majority of the 3.8 million people who backed the far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the first round, he must surely expect to improve on his 1.4 per cent lead from the first round on April 22.

To snatch victory from defeat's grasp, Mr Sarkozy must prove the accuracy of the French equivalent of not counting chickens before they are hatched, as cited in Le Figaro's projections: to sell the bear's skin, one must first kill the bear.