ISTANBUL // For several years Ahmet Akkaya has spent most of his mornings and evenings in his favourite cafe in Istanbul, chatting with friends and smoking shisha.

But a new law banning indoor smoking of shisha, or nargile as it is known in Turkey, is threatening to leave him out in the cold.

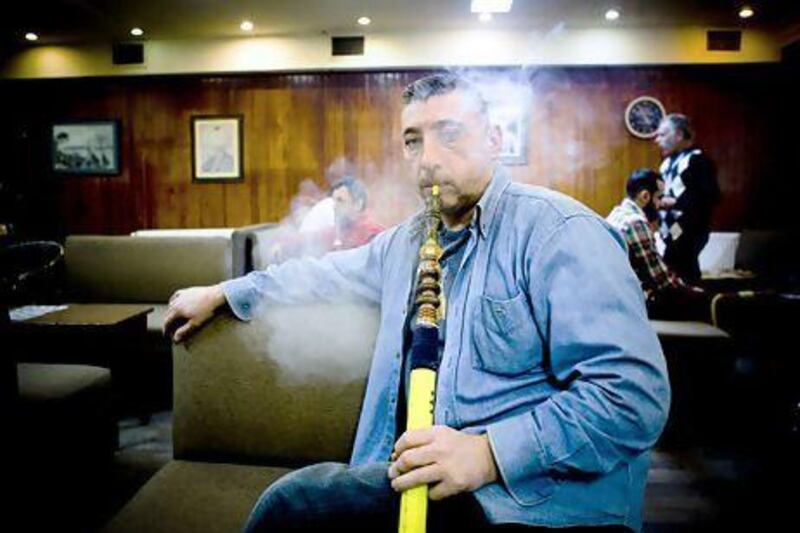

"Where will I meet my friends?" Mr Akkaya, 47, said as thick smoke from dozens of water pipes like his own drifted through the Cinaralti Nargile Cafe near the Bosphorus. "In the summer it's not a problem. But what am I supposed to do in winter?"

Mr Akkaya showed off the sticker with his name on the hose he was using. The hose was adorned with the colours of Fenerbahce Istanbul, his favourite football team. "They know me here, they prepare my nargile with cappuccino flavour as soon as I walk in."

But if all goes according to government plan, he will not be able to smoke inside the cafe much longer. A law requiring shisha cafes to comply with an indoor smoking ban already in place for cigarettes, pipes and cigars since 2009 was published in Turkey's Official Gazette last month. It gave the cafes and their customers a grace period of six months.

A second set of rules, published in the Official Gazette last week, makes it illegal for shisha cafes to operate near schools and bans their use by youngsters under the age of 18 from July 27 this year.

The new laws have people like Mr Akkaya bewildered and sometimes angry. They reject the comparison with cigarettes and argue that smoking a shisha over several hours is less harmful and more cultivated than having a quick cigarette.

For Mr Akkaya, who runs a snack kiosk in a tourist area near the Golden Horn, shisha is part of an unhurried and sociable Turkish way of life.

"There is a culture of conversation connected with it," he said. "I have a nargile at home, but I never use it. I am always smoking here, among other people."

Mr Akkaya said he supported restrictions on the use of alcohol, but was against the indoor ban on shisha, and predicted people would end up drinking more alcohol if it was enforced.

"Next year in winter, when I want to meet my friends, I will call them and say: 'Let's meet in this bar or in that bar," he said. "Is that better?"

But politicians, doctors and health campaigners say the aromatic smell of shisha hides a serious health risk.

Cevdet Erdol, a legislator from the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) who drafted the new shisha rules, argued last year that the tobacco in one shisha was "equal to the poison of two and a half packs of cigarettes".

Goksel Kiter, a lung specialist at the Pamukkale University in Denizli, told the state-run Anadolu news agency this month that though young people especially were convinced that the fruit-flavoured shisha tobacco was less harmful than cigarettes, in fact it "contains 10 times more nicotine than a cigarette".

Yesilay, a non-government group campaigning against tobacco and alcohol use, said "the nargile epidemic is a widely ignored and rapidly growing public health risk".

The rules are also designed to bring the trade in smuggled - and untaxed - shisha tobacco under control.

Quoting data from TAPDK, the state body charged with controlling Turkey's tobacco and alcohol sector, the pro-government Sabah newspaper reported last month that the state was losing about 500 million lira (Dh1.04 billion) a year in tax revenue because of the widespread use of smuggled shisha tobacco in cafes.

Believed to have been brought to Turkey from Ottoman Egypt several centuries ago, shisha has enjoyed a boom in recent years as it became stylish among young people and the number of Arab tourists rose.

Nurullah Poyraz, a waiter at the Nargilem Cafe in Istanbul, said the law meant that the good times were over. "It's bad for us," he said.

Nearby, Arkin Kocaman, who works at the Milano Cafe, agreed. "Take today," he said, pointing to empty chairs and tables in front of the cafe on a cold and drizzly February day. "How can people sit outside in that kind of weather?"

Mr Kocaman said there might be ways to save the indoor shisha tradition. "Maybe they could allow some kind of special air circulation system in the cafés," he said.

Another solution, practised at the Nargilem Cafe already, is to provide outdoor gas heaters, wind breakers, shawls and umbrellas for customers.

Gurkan Aydemir, a customer who was sharing a shisha with a friend over a game of backgammon at an outside table at the cafe, said that although he had to sit outside in the cold, he agreed with the ban.

"We know it's unhealthy, and we don't want to cause harm to other people," he said.

Mr Aydemir, a member of the AKP, said the government was right to clamp down on unhealthy habits like smoking because they were costing the tax payer huge sums of money in payments for cancer treatment.

tseibert@thenational.ae