The corruption trial of the former French president Jacques Chirac has begun in Paris without its main character, whose health has been deemed too poor for him to take part.

Mr Chirac, who will be 79 in November, has always insisted he should be treated as any other citizen and appear in court to answer the accusations against him.

He protests his innocence in a case dating from his 18 years as mayor of Paris and forming part of the background of corruption allegations that haunted him during two terms as president.

Until last week, Mr Chirac seemed resolute in his desire to stand trial. But at the weekend his lawyers confirmed they had written to the judge about the deterioration in his health.

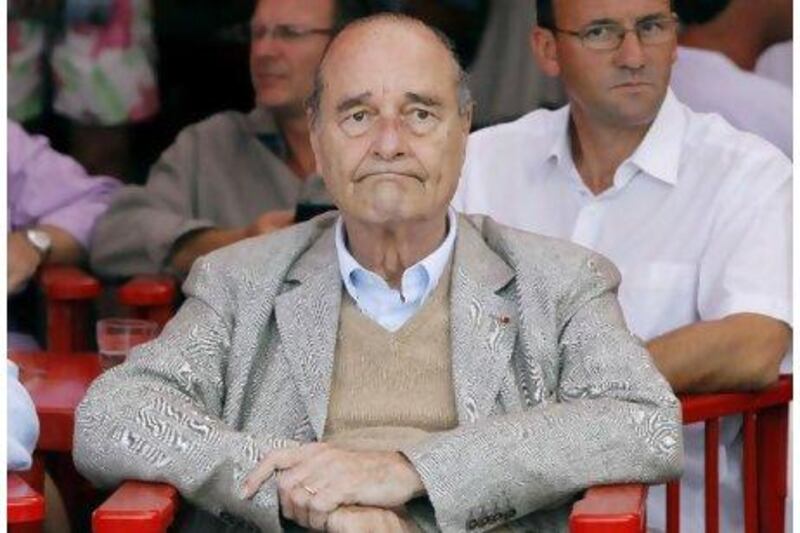

In public appearances this year, he has seemed a shadow of the robust, ebullient figure of his presidency.

Last month, Mr Chirac made his customary outing for apéritifs to the harbour front of St Tropez while staying at the Riviera home of his friend, the wealthy businessman François Pinault. He posed happily for photographs and chatted to tourists, but looked frail and was unsteady on his feet.

A neurological report, commissioned by the former president's family, described him as being in a "vulnerable" state that made it impossible for him to answer questions about the past.

One newspaper, the Journal du Dimanche, has likened his symptoms to those experienced by stroke victims or people with Alzheimer's disease.

Reports in that newspaper and others say he has become seriously forgetful in company, expressing ignorance of the current French prime minister, François Fillon, or the events of the 1968 Paris Spring, when students and workers rebelled against the then president, Gen Charles de Gaulle.

Mr Chirac's adopted daughter, Anh Dao Traxel, has told the French media he failed to recognise her when their paths crossed outside his Paris home this year.

Mr Chirac's wife, Bernadette, previously denied that her husband has Alzheimer's, but has confirmed that he has health problems related to a stroke suffered before leaving office in 2007.

In his ruling after studying the medical report, Judge Dominique Pauthé said: "Mr Chirac will not be ordered to appear in person and as a result shall be tried in his absence, represented by his lawyers."

He quoted a letter from Mr Chirac's lawyers saying he wanted the trial to proceed as a process that was "useful for our democracy" and demonstrated "all to be equal under the law".

Prosecutors did not exclude the possibility of a second medical opinion but raised no immediate objection.

The trial, due to open in March, was delayed until this week while the courts ruled on a constitutional challenge lodged by one of the nine co-defendants, who include a grandson of Gen de Gaulle among those said to have benefited from corrupt practices at Paris city hall. It is scheduled to run until Sepember 23, though judgment is likely to be later.

Mr Chirac is accused of embezzlement and abuse of trust in orchestrating a corrupt system of fictitious employment between 1992 and 1995. The names of political friends were allegedly added to the payroll though the jobs for which they were paid did not exist.

Prosecutors claim that the motive was to increase Mr Chirac's power and that of his Gaullist party, the Rally for the Republic (RPR), forerunner of the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP), of which he was also the co-founder and which rules France today.

The first president of the UMP was Alain Juppé, who later served as prime minister and is now the French foreign secretary. As a close aide of Mr Chirac, he was implicated in the "fictitious jobs" scandal and received a suspended sentence and temporary exclusion from holding civic duty before making the remarkable comeback that took him to his present high office.

Mr Chirac, who maintains he is innocent of wrongdoing and always acted in the interests of Parisians, faces up to 10 years' imprisonment if convicted, though observers say any jail sentence would almost certainly be suspended. Without admission of guilt on Mr Chirac's part, a deal was reached last year in which the UMP refunded more than US$2 million (Dh7.35m) of payments made for allegedly non-existent jobs.

French public opinion seemed divided on the new development yesterday. This split reflects sharply conflicting views of Mr Chirac, derided by the left and some on the right he once represented but repeatedly voted the country's most popular politician since he left the Elysée.

In internet discussions, some contributors said it was right that an ailing former head of state should be spared the ordeal of a court hearing; others felt the rule of law should apply. Anti-corruption campaigners included among plaintiffs in the case even posed the question as to whether the medical condition was just an "umpteenth attempt to get out of the trial".

A cartoon in the provincial newspaper Nice-Matin mocked an "epidemic of anosognosia" or loss of awareness sweeping France and claiming, among its victims, Mr Chirac, along with - in differing contexts - the president, Nicolas Sarkozy, and the former International Monetary Fund chief, Dominique Strauss-Kahn.