LONDON // The prospect of the disintegration of the Anglican church worldwide deepened this week after the Church of England voted to ordain women as bishops. With the 80 million-strong Anglican Communion already deeply and increasingly divided over the ordination of homosexual priests, the vote by the General Synod - the Church of England's ruling body - raised the spectre of a split within England, on top of the potential schism in the church worldwide.

On July 20, the once-a-decade Lambeth Conference begins, supposedly an opportunity for the Anglican leaders from across the globe to come together and sort out their differences under their leader, the archbishop of Canterbury: a post currently held by Rowan Williams. For years, more than 200 traditionalist bishops, mainly from Africa, Asia, South America and Australia, have decided to boycott the conference. Last month, they held a rival gathering in Jerusalem where they condemned the "false gospel" that had led to the ordination of homosexuals.

The group, calling themselves the Global Anglican Future Conference (Gafcon), also deplored the "spiritual decline of the most economically developed nations". Undoubtedly, these traditionalists will see the Church of England vote on female bishops as further evidence of the way that the Anglican Communion in countries such as Britain, the United States, Canada and New Zealand are veering towards an unacceptably liberal position on sexuality.

Mr Williams, forced to react to such a challenge, has urged these conservative bishops to "think carefully about the risks entailed" in breaking away. However, they do not seem to be listening and are even challenging the historical position of the archbishop of Canterbury as titular head of the church worldwide. That has already brought a stiff response from Lambeth Palace, the archbishop's administrative headquarters. "It is ludicrous to say you do not recognise the archbishop of Canterbury or the see of Canterbury. By doing away with the role and the place, these people are becoming a Protestant sect," a spokesman for Mr Williams said.

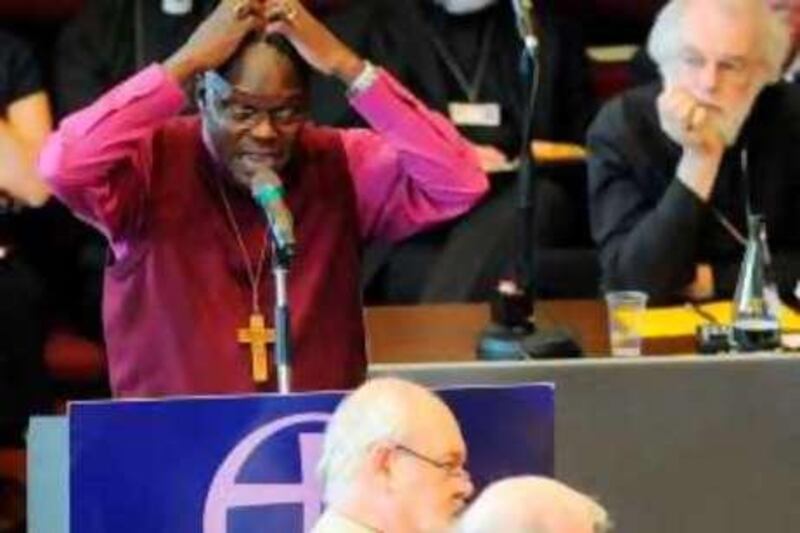

With the church already so hopelessly divided over the issue of homosexual priests in general and, in particular, the ordination of an openly gay bishop in the United States five years ago, the Church of England's decision to press ahead with the consecration of female bishops was, perhaps, the last thing it needed. But after a six-hour debate at the synod meeting in York, which saw one bishop and two clergymen reduced to tears as they made speeches, 468 members not only voted in favour but threw out a plan that would have allowed traditionalist opponents to have their own, "male-bishop-only" dioceses.

More than 1,300 clerics have already threatened to split away from the Church of England if women were approved to become bishops and the Right Rev Michael Scott-Joynt, the bishop of Winchester, warned after the vote on Monday night that the decision could lead to defections from the church. He said that those Anglo-Catholics and conservative evangelicals who believe the Bible stated that bishops should always be male, might join Gafcon.

Bishop Scott-Joynt said the synod's rejection of a compromise to allow conservatives to have, in effect, men-only dioceses was "mean-spirited". "The manifest majority was profoundly short-sighted," he said. "At every point it could have offered reassurances, but it did not do that. We've got people talking about defection - we've got a lot of soul-searching to do." The Right Rev John Broadhurst, the traditionalist bishop of Fulham, feared the vote would inevitably lead to a split. He told the BBC: "I think a lot of us have made it quite clear if there isn't proper provision for us to live in dignity, inevitably we're driven out. It's not a case of walking away."

But Robert Key, a Conservative MP and synod member, who supported the move, said it was time for the church to stop "navel gazing". "It is a good day for the Church of England, and it is a good day for the country because our national church, the church by law established, is actually now in step with most of the country and what people feel," he said. However, even some supporters of the move towards making women bishops in a church that ordained its first female priest only 12 years ago, were unhappy that proposals to accommodate traditionalists were not accepted. The Right Rev Stephen Venner, bishop of Dover, had to be comforted by fellow synod members after he broke down in tears on the podium.

"I have to say that for the first time in my life I am ashamed," he said. "We have talked for hours about wanting to give an honourable place for those who want to disagree and we have turned down almost every realistic opportunity for those who are opposed to flourish." He accused the church of simply "talking the talk" about being inclusive. "Is this the Church of England at its best?" he asked. "I have to say I doubt it."

Gerry O'Brien, a traditionalist opposed to female bishops, was hissed during his speech to the synod, which, normally, is a genteel and well mannered gathering. Alluding to the split between conservatives and the churches in the United States and Canada after the ordination of a gay bishop, Mr O'Brien said: "We can force people out of the Church of England but I think the experience in America says you can't force people out of the Anglican Communion, because there are a lot of archbishops elsewhere in the world who will be more than ready to provide the support."

But Christina Rees, chair of Women and the Church, embraced the decision. "It is very good for the church and very good for women and also good for the whole nation," she said. Privately, church leaders are hoping that talk of a split will fade away, much as it did in the 1990s when passions were running high over the ordination of female priests. However, divisions within the Anglican church are deepening worldwide, particularly over liberal attitudes in Britain, United States and 'old commonwealth' towards sexuality.

The Lambeth Conference will try to build bridges between the two sides but the task, already a tough one, has been made immeasurably more difficult because of the planned boycott. Mr Williams, the archbishop, accepts this. "I'm saddened by the decision of those bishops who've chosen not to attend," he said. "It inhibits the life of the whole church when one part of it decides to disengage." As one synod member said yesterday: "Considering that this is a church based on the concept of love and peace, there doesn't seem to be much of it around at the moment.

"In reality, it does not seem like one church anymore - we seem like two churches moving in different directions." @Email:dsapsted@thenational.ae