ISTANBUL // Erdal Kabatepe is certain that Turkey's appetite for joining the EU is ebbing away. After all, the money he has been using to promote the country's European perspective is doing just that. "It is difficult to collect membership fees," said Mr Kabatepe, head of the EU-Turkey Co-operation Association, or Turkab, a pro-European lobby group. Turkey's EU bid "is a lost case,", he said. "The government is looking towards the Arab world and Russia."

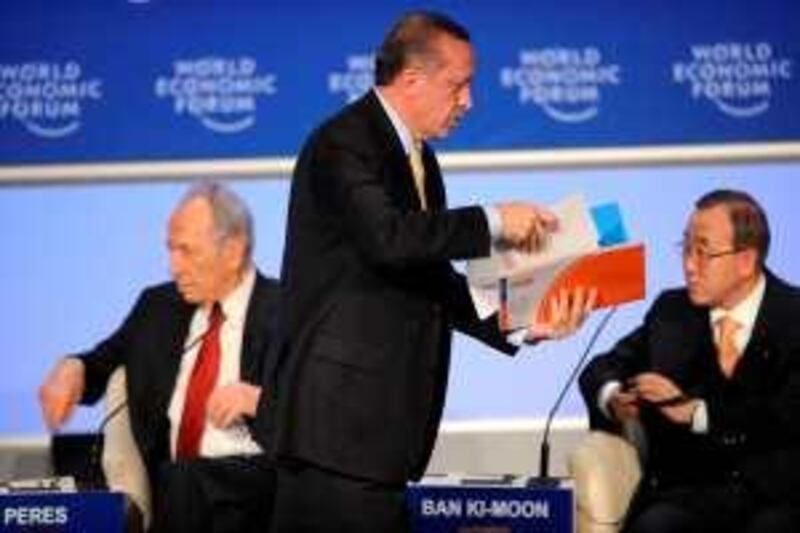

Ever since the prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, won praise from Middle Eastern countries and raised eyebrows in the West by storming out of a heated debate with the Israeli president at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, Turks have been debating a question that touches the identity of this Muslim, but secular country: is Turkey about to turn away from the West? Mr Kabatepe is not alone in wondering if Ankara has lost interest in becoming ever deeply integrated into western institutions such as the EU under the government of Mr Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party, or AKP, which has roots in political Islam. "Will we be a religious state or an EU member in 10 years from now?" the daily newspaper Vatan asked last weekend, when it started a series of articles that deal with the question of where Turkey is headed.

Critics and opposition politicians say Mr Erdogan's government has been working to change the strategic outlook of a country that has historically tried to become an integral part of the West. Turkey became a member the Council of Europe in 1949, joined Nato in 1952 and signed an association agreement with the forerunner of today's EU in 1963. It is also a partner of Israel and has been conducting a close military co-operation with the country since 1996.

But under Mr Erdogan's government, Turkey has also become much more active in Middle Eastern affairs in recent years and has done much to mend ties with countries such as Iran and Syria, seen as promoters of terrorism in the West. The government rejects the accusation that it is steering Turkey towards the Middle East and argues that it was Mr Erdogan and the AKP who presided over the start of EU membership negotiations in 2005, a goal that had eluded previous Turkish governments for decades.

Membership talks have proceeded slowly, however, leading to a sense of frustration in both Ankara and Brussels. At the same time, Mr Erdogan has been accused of putting Turkey's alliance with Israel at risk by harshly criticising Israeli actions in Palestinian territories while demanding a political role for Hamas, an organisation the West says is bent on destroying Israel. Turkey is the only Nato member that has welcomed a Hamas delegation for talks.

Mr Erdogan's performance in Davos and the reactions it triggered in the Middle East are viewed by some as further proof of the new course Turkey is taking in international affairs. In a sign of protest against not having received adequate time to respond to a defence of the Israeli attack on Gaza by Israel's president, Shimon Peres, Mr Erdogan left the stage during a panel discussion. In the days after the Davos incidents, there were demonstrations in support of Mr Erdogan in the Gaza Strip. Representatives of Turkey's Jewish community have reported an increase in anti-semitism.

Internal critics and some international experts say that Turkey's position in world affairs is shifting. "There are powerful long-term forces at work in Turkish society and politics, and these are likely to reinforce an already strong sense of Turkish nationalism and exceptionalism," Ian Lesser of the German Marshall Fund, a group promoting greater understanding between the United States and Europe, wrote in a recent report.

"The net result may well be a steady augmentation of Turkey's international agenda, in which the western dimension, including US-Turkish relations, EU candidacy, and the role of Nato are relatively diminished." During a visit to the EU headquarters in Brussels last month, opposition leader Deniz Baykal said that under Mr Erdogan and the AKP, Turkey was turning away from secularism and the West. "What we are witnessing is a conservatism that is a return to Middle Eastern values," Mr Baykal said in reference to Turkey's Ottoman past, according to press reports. "It is unacceptable [for Turkey] to be part of the same region as Hamas and Hizbollah," Mr Baykal said.

In a report for the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, a think tank, Mark Parris, a former US ambassador to Ankara, wrote that "in terms of foreign policy, the AKP's record is marked by Turkey's closeness to Sudan, Russia, and Iran, and paints an alarming picture". For Mr Erdogan's domestic critics, views like that are a confirmation of their own concerns. "Finally, the outside world is also becoming uncomfortable," Gungor Mengi, the editor of Vatan, wrote recently. The AKP is accused by the opposition of having a secret agenda to turn Turkey into an Islamic state, something the AKP denies.

But even some observers who are known for their criticism of the Erdogan government doubt that Mr Erdogan's Middle East policy is a sign of a strategic realignment and say Turkey would have nothing to gain from such a manoeuvre. "With its secular and democratic structure and values, Turkey is a country that serves as an example for the Arab street," Fikret Bila, a columnist, wrote in Milliyet, a daily newspaper, under the headline: "Turkey does not break away from the West."

tseibert@thenational.ae