Divided EU leaders inched closer to agreeing on an economic recovery plan for virus-hit Europe on Thursday as the European Central Bank chief warned that action was urgently needed.

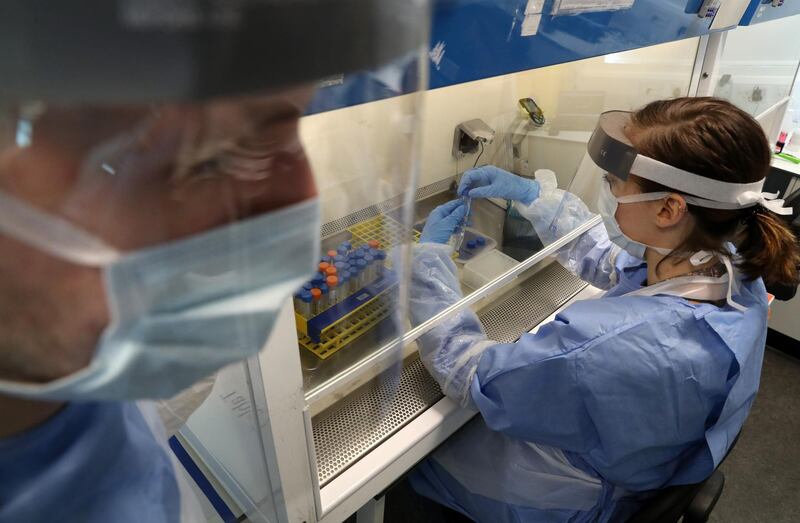

The EU's 27 leaders met by video conference as fresh data showed that the European economy was in freefall, struck down by a series of national lockdowns to thwart a wave of more than 110,000 confirmed Covid-19 deaths across the bloc.

After four hours of talks, the leaders agreed to task the European Commission, the EU's executive arm, to come back with a plan early next month that would both gauge and answer the needs to fix the European economy.

"A consensus is being formed to strengthen Europe's strategic autonomy" among the 27 member countries of the European Union, French President Emmanuel Macron said after the talks.

Given bitter recriminations ahead of the talks, expectations for a breakthrough had been low.

As expected, leaders agreed that any plan would take place through the EU's long-term budget, the Brussels-based money pot that usually goes to farming subsidies and development aid to eastern and southern Europe.

This was demanded by German Chancellor Angela Merkel, the bloc's most influential leader who has stood firmly against more ambitious proposals backed by Italy and Spain, most notably joint EU borrowing.

The small step on Thursday came as ECB chief Christine Lagarde told the leaders that in the bank's worst-case forecast, the bloc's gross domestic product could fall by as much as 15 percent in 2020 as a result of the pandemic.

She warned the 27 members that "there was a risk of acting too little, too late," a source said.

The outbreak of the coronavirus crisis in Europe, one of the areas worst hit by the disease in the world, has exposed some of the bloc’s most enduring divisions. In particular, tensions between northern and southern nations on fiscal policy have come to the fore throughout the protracted and sometimes unedifying wrangling.

In the lead-up to the meeting, consensus had been building for a fund based on grants financed through EU debt instruments. The Spanish government, led by Pedro Sanchez, has called for a €1.5 trillion fund, a proposal that has gained traction.

However, opposition from northern nations such as the Netherlands still remain. The Netherlands, Austria and Germany have been resistant to calls from France, Spain and Italy - which are perceived by their neighbours to the north as more fiscally profligate - to any pooling of sovereign debt.

The impasse over the Covid-19 bailout has pitted the EU’s leading members, France and Germany, against each other. Berlin swiftly opposed the prospect of issuing so-called corona bonds to cushion the impact of the bailout.

In her speech on Thursday, Ms Merkel once more broke with France, saying that the fund should be linked to the next seven-year EU budget. France and Italy had previously suggested a completely separate instrument should be used in the Covid-19 stimulus package. Negotiations over the budget are also one of the principal areas open for discussion in the council’s virtual summit.

Earlier in April, EU finance ministers signed off on a €540 billion package of measures to support the bloc’s battered economies. Those measures included €240 billion of credit from the European stability mechanism, a €200 billion fund from the European Investment Bank and €100 billion for the European Commission’s jobless reinsurance plan.

These funds still need to be expanded and quickly, however, distrust within the bloc is growing. Italy and Spain, in particular, have called for a conspicuous display of generosity and solidarity after Europe failed to intervene fast enough as the coronavirus overran their health systems.

The virtual meeting of EU leaders followed Wednesday’s meeting of EU foreign ministers. While discussions centred around the Covid-19 outbreak, the talks led by Josep Borrell, the EU foreign affairs chief, also focused on the intensifying conflict in Libya.

German press have reported that the country has pledged to contribute up to 300 troops to the EU’s new Libyan naval mission. The initiative, named Operation Irini after the Greek word for “peace”, aims to curb the flow of arms into the North African country which has been plagued by violence since a Nato-backed intervention in 2011.

Other EU nations are yet to announce their own contributions to the mission, which was repurposed to enforce a long-flouted UN arms embargo following an international conference on Libya in Berlin in January.

The EU’s previous mission in the Mediterranean had been oriented around migrant search and rescue. Since the meeting in early 2020, which had been aimed at producing a lasting ceasefire in Libya, the country's conflict, particularly in the west, has worsened.