MARSEILLES // The French government is resisting mounting pressure to abandon a planned debate on Islam that has split the ruling party, dismayed Muslims and united leaders of all the country's main religions in firm opposition.

In its first joint communiqué since being created last November, the Conference of French Religious Leaders said the approach of presidential elections, scheduled for one year from now, was not the right time for a discussion that could stigmatise Muslims and increase prejudice.

Widespread criticism of the debate, scheduled for Tuesday, underlines the government's failure to prove its claim that it is intended to be about France's legally enshrined secularism and not solely on Islam.

Even the prime minister, François Fillon, has declared his opposition. He confirmed yesterday that he had no intention of taking part, though it was stressed that the decision was taken weeks ago with President Nicolas Sarkozy's agreement.

Leaders of the Roman Catholic, Muslim, Protestant, Jewish, Orthodox Christian and Buddhist faiths said in their statement: "The acceleration of political agendas may, on the eve of electoral events important to the future of our country, blur the vision and cause confusion that can only be detrimental."

While describing debate as healthy for democratic society, the Conference of French Religious Leaders asked: "Is a political party, even if it is in the majority, the right forum to lead this [dialogue] by itself?"

The statement's 12 signatories include Mohammed Moussaoui and Anouar Kbibech, respectively president and secretary general of the French Muslim Council.

After Catholicism, Islam is France's biggest religion. The Muslim population is estimated at between five and seven million, most having roots in North and sub-Saharan Africa.

Mr Sarkozy is said to be anxious that the discussion should go ahead as planned, but his cause is not aided by a ban on face-covering veils that takes effect less than a week later.

Critics say the so-called "burqa ban" is unnecessarily divisive, given that fewer than 3,000 Muslim women in France are estimated to wear them. A French-Algerian businessman has raised hundreds of thousands of euros in an appeal fund to pay the fines of any woman prosecuted under the law.

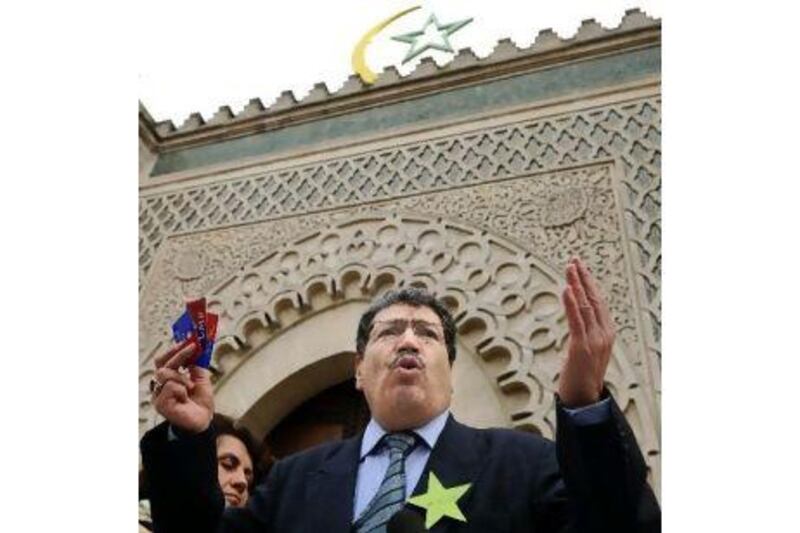

It has fallen to Jean-François Copé, the president of the president's ruling centre-right UMP party, to lead the way in defending the debate.

Mr Copé is adamant that there is no hostile or aggressive motivation.

He has called for "an end to the hysteria" and claims the interest of equality for all faiths will be served by discussion on how secularism, established by a law passed in 1905 and regarded as a cornerstone of France's republican values, is respected in practice.

Exasperated by party divisions at the very top, he accused Mr Fillon on live television of "not being a team player". Mr Fillon responded in chilly fashion, reminding his colleague that "you can't air your differences with the prime minister like that on television".

Then François Baroin, the government spokesman and finance minister, was "invited" by the Elysée to clarify his position after calling for an "end to all these debates" and a return by the UMP to deeper republican principles.

He appeared to do so, only to return to the theme on French television yesterday, saying he withdrew "not a single word".

Abderahmane Dahmane, a former presidential adviser on diversity, has urged French Muslims to wear green stars in protest at the debate and against "Islamophobia".

The suggestion, which recalls the yellow stars that Jews were forced by the Nazis to wear in the Second World War, has been condemned as "grotesque" by Richard Prasquier, the leader of a Jewish secular group, the Representative Council of Jewish Institutions.

Mr Prasquier, who supports next week's debate as a valid response to French people's concerns, told Agence France-Presse: "It is unfortunately part of a wider movement that mixes everything up and makes everything equate to the Holocaust."

Political figures who have spoken out in favour of the debate deny that there is any connection to UMP efforts to win back middle France voters who have turned to a more simplistic answer to their concerns on immigration and crime.

But Martine Le Pen's openly nationalist Front National wastes no opportunity to exploit signs of government weakness in stemming an influx of migrants. It welcomes the debate as playing directly into its hands as it seeks a major political breakthrough.

The controversy is probably the last thing Mr Sarkozy needs as he approaches the most difficult period of his presidency, with some members of his party beginning to question whether he should be the candidate next year.

From French media commentators yesterday, the advice was overwhelmingly that he should think again.

The left-of-centre Le Monde offered a plain message: "There is still time for him to come out of denial, take a wiser path and give up this debate."

Even the conservative daily Le Figaro, while concluding that a political party could hardly be blamed for reflecting on major issues, admitted that the "content, objectives, appropriateness and timing" were questionable.