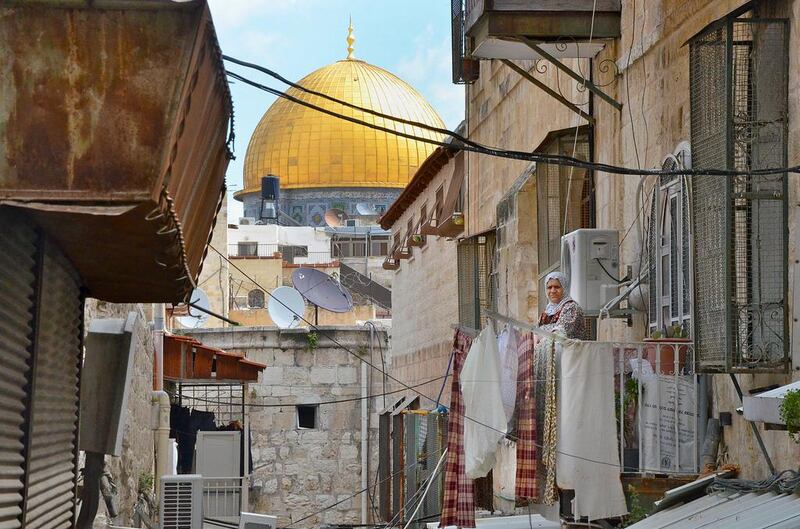

EAST JERUSALEM // The Sub Laban family has been living in the Muslim quarter of East Jerusalem’s Old City for 62 years.

But now not a day passes without the threat of forced eviction.

“I’m living with this complete uncertainty every day,” says Palestinian Ahmad Sub Laban, who lives in a two-bedroom apartment with his parents, wife and two children.

“In the past weeks I couldn’t leave the house. It’s had a huge effect on my career and children.”

The Sub Labans are the latest targets in an aggressive legal campaign by an Israeli settler group to force long-time Palestinian residents out of the area.

The family rented the three-storey apartment in 1953 from the Jordanian custodian of East Jerusalem, with guaranteed protected tenant status.

This status allows tenants to live in their homes indefinitely, as long as they continue to pay rent and live in the property continuously.

The Sub Labans pay rent. But they say Israel has been trying to evict them since it annexed East Jerusalem in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, claiming that a Jewish family owned the property before 1948 – when the first Arab-Israeli war was fought between the newly formed state of Israel and a military coalition of Arab states and Palestinian Arab forces – despite that family not being present to make a claim.

Up to 700,000 Palestinians fled homes or were expelled by Israel in the 1948 war. Jordan took control of East Jerusalem after the war and about 10,000 Jews left their homes in what became the West Bank and Gaza.

Between 1967 and 2001, the Sub Labans say the government tried various means of forcing them out of their apartment, including allowing settler families to move into neighbouring apartments in their building, and allowing settlers to block the front entrance to their home, forcing them to enter via a back way.

In 2001, an Israeli judge visited the property and ordered the front entrance to be made accessible.

Five years ago, however, the Jewish settler NGO Ateret Cohanim was granted ownership of their building by the Israeli custodian of absentee property and is again trying to evict the family through the courts.

Last month the Jerusalem magistrate’s court revoked the family’s protected tenant status after Ateret Cohanim presented statements from witnesses claiming the family had not occupied the apartment continuously.

The family says the witness statements are false. They can now be evicted but have filed an appeal in the district court that will be heard on May 31.

The latest attempt to evict the Sub Labans is part of a growing campaign of Jewish settlement in East Jerusalem, which Palestinians want as the capital of their independent state. Israel claims it as part of an undivided Jerusalem.

Mr Sub Laban, 35, who works for an NGO, says the threat of eviction has forced him to stay inside the apartment, which is just 150 metres from the entrance to the Al Aqsa mosque.

In late February his son Mustafa, 9, just managed to close the front door on Ateret Cohanim activists and their security guards who were trying to force their way in.

That was the organisation’s third, and latest, attempt to enter and occupy the Sub Labans’ home this year.

Since the start of March, hundreds of residents, Palestinian and Israeli activists, NGO representatives and diplomats have kept a constant presence outside the Sub Labans’ building to prevent eviction attempts by Ateret Cohanim.

Betty Hershman, director of international relations and advocacy at Ir Amim, an equal rights advocate for Palestinians and Jews in Jerusalem, says efforts by settlers have become aggressive.

That Ateret Cohanim is legally allowed to evict the Sub Labans from their home, “demonstrates the duality of the system and the inherent inequality in property law”, she says.

Ateret Cohanim, based in the Muslim quarter of the Old City, has been a major driver of the campaign to take over Palestinians’ homes.

Its growing influence in Israeli courts and its aggressive settlement agenda have displaced about 50 families in the past five years.

Eighty Jewish families affiliated with Ateret Cohanim now live in homes from which Palestinians were evicted in the Muslim and Christian quarters of the Old City.

The organisation runs a large religious school in the area and last September moved nine settler families into nine apartments in the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Silwan.

Another settler organisation, Elad, took over four properties in Silwan in March, arriving in the middle of the night.

Last year, Ateret Cohanim bought part of a historic East Jerusalem post office from Bezeq, an Israeli telecommunications company, and turned it into a pre-army training school.

Under Israeli law, Jews who left their properties in East Jerusalem in 1948 can go to court and have them returned, unlike Palestinian refugees who have no legal recourse to reclaim properties from which they fled that same year.

“If there’s this attempt to give Jews their property back from before 1948, on lands that were given to the Palestinians under the Jordanian government, then we should be able to do the same and get back our lands that are now in Israel since ’48,” Mr Sub Laban says.

The director of Ateret Cohanim, David Lauria, did not respond to requests for comment.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae