Tucked away forgotten in boxes, mundane bureaucratic documents from a former empire can tell important stories.

Two years ago, in the Ottoman Archives of Istanbul, Zackary Foster was researching his doctorate on the causes of the worst famine in the modern history of the Levant.

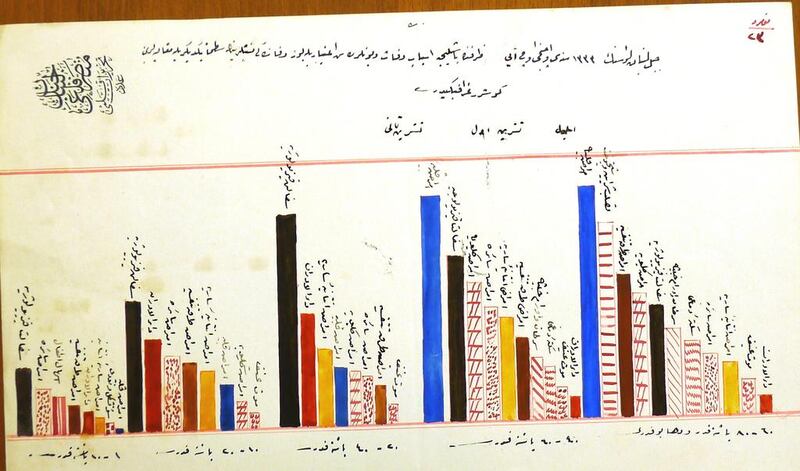

The graduate student at Princeton University stumbled upon beautifully hand-drawn and coloured graphs depicting death rates in Lebanon in 1915-1916, a year-and-a-half after the outbreak of the First World War. In one of the graphs, the causes of death were broken down by age group, and the months of September, October and November of 1915 in the district of Mount Lebanon, which during the First World War included the districts of Jezzine, the Shuuf, Beirut, Keserwan, Batrun and Kura.

Mr Foster found the primary cause of death for the 1-40 age groups in this chart to be sefalet-i fiziloyojiye (dark brown on the graph), which he says “loosely translates to physical abjection, poverty or destitution”. The other common causes in most age groups were tuberculosis (bright red), infectious diseases (spotted red) and communicable diseases (bright yellow). Other graphs reflected more of the same, with deaths in one graph to typhus – one of the highest.

“People were dying en masse from typhus and other diseases in the spring of 1916: 482 total deaths in March 1916; 784 deaths in April 1916; and 444 deaths in May 1916,” he says.

“Deaths were rapidly increasing in the spring of 1916.” In other words, the data shows that according to the Ottomans, “there was no famine, only disease”.

“Ottoman Turkish had very specific words to mean famine, hunger or starvation: meja’at or açlık. Those words appear nowhere in any of the documents I looked at. The state did not like to talk about famine. But diseases shifted the focus of blame away from the state, onto the people themselves,” he said.

rghazal@thenational.ae