PHILADELPHIA // Every November, Sivan Kartha joins 14 other men and women in a conference room in Chicago to decide how much time remains before “midnight” – when the human race annihilates itself.

Last year, said Dr Kartha, a senior scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute in Massachusetts, there were some bright spots: the Paris climate accord, the Iran nuclear deal. Even so, he and his fellow experts, drawn from various fields, decided to leave the hands of the Doomsday Clock at three minutes to midnight.

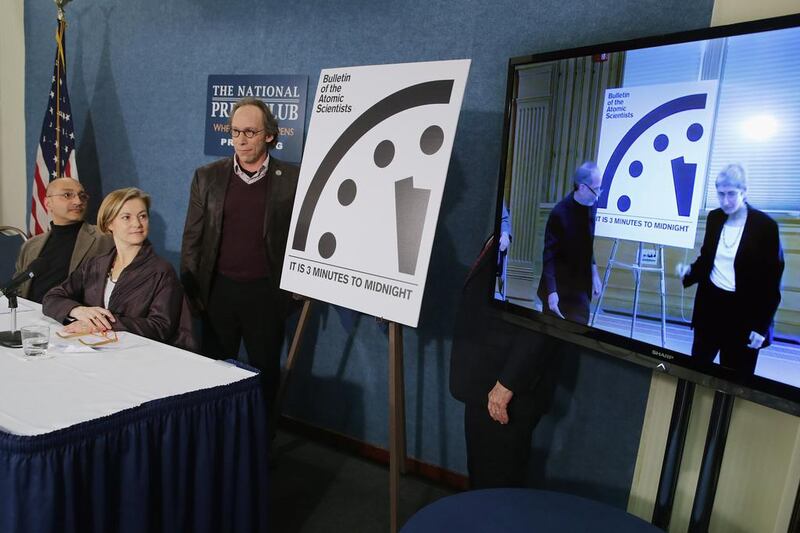

Rogue nuclear attacks are still possible. The effects of climate change are quickening. "The Clock ticks," the experts – members of a special panel convened by a Chicago-based journal called the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists – wrote in their public statement in January. "Global danger looms. Wise leaders should act – immediately."

Every year since 1947, the Doomsday Clock – a symbolic timepiece often featured on the journal’s cover – has been alerting humankind to imminent dangers. The clock focused on nuclear threats during the Cold War, but over the past decade it has begun to factor in climate change as well.

In 2014, according to the Doomsday Dashboard on the Bulletin's website, sea levels rose an average of 55.72 millimetres, and atmospheric carbon dioxide rose to 399.23 parts per million.

These factors keep the world perilously close to midnight. The only time it has been closer was in 1953, after the United States and the Soviet Union tested hydrogen bombs. "Only a few more swings of the pendulum, and, from Moscow to Chicago, atomic explosions will strike midnight for Western civilisation," the Bulletin reported then.

The clock now is only a minute further away. “Climate change is something that is inexorably progressing. As long as we’re emitting greenhouse gases, how could the clock do anything other than go forward?” Dr Kartha said.

The Bulletin itself, in its bi-monthly issues, deals with security and public policy issues that may pose fundamental dangers. It was founded in 1945, soon after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, by a group of American scientists who had developed nuclear weapons during the Second World War. The objective of the Bulletin, said Rachel Bronson, its executive director and publisher, was "to alert the world of the devastation associated with this technology and the need to think very smartly about how we can assure that [nuclear weapons] would never be used again."

The clock was another effort in that direction, a metaphor to indicate that “we didn’t have time to waste”. It was first set at seven minutes to midnight, Dr Bronson said, and every January, as the new setting is announced, it starts a conversation about global peril.

“Other organisations use the clock to frame their conversation,” she said. “So we’ve seen in a disarmament bill entered into the floor of the parliament in Scotland saying it’s three minutes to midnight, and here’s what we need to do. We’ve seen United Nations conferences organised around the time.”

The minute hand of the clock has shifted forward and back. In 1991, with the Cold War at an end and both the US and Russia beginning to disarm their nuclear weapons, the clock delivered its sunniest-ever prognosis: 17 minutes to midnight.

But the deterioration of the environment and global warming has rolled that progress back.

“In 2006, we added climate change to the Doomsday Clock,” Dr Bronson said. “The board had already been debating for a decade whether or not to do that.”

Dr Kartha joined the board in 2012. Scientists and experts serve a maximum of two three-year terms on the board before rotating out. Board members keep in touch through email and conference calls throughout the year, meeting once in Washington in June and then again in Chicago in November, to set the clock.

The experts give presentations or talk through developments over the previous year, trying to see if the momentum is pushing the world towards or away from disaster.

“At the last meeting, much of the discussion was about the Iran nuclear deal,” Dr Kartha said. “There was a lot of discussion about how it was perceived in different areas – in the US, Europe, Iran. Discussions about what the media may have gotten right or wrong.”

The debates can, Dr Kartha said, get passionate, “perhaps even heated. But always respectful. It has never come even remotely close to coming to blows.”

There is rarely unanimity on how to set the clock, but there is always consensus. “Everyone is content that all the arguments have been placed on the table,” he said.

The process of setting the clock is not a cheery one.

“It’s hard to say it’s a meeting to look forward to, because it’s very grim,” Dr Bronson said. “The meeting is interesting, but we do walk out with our shoulders slumped. The news is rarely good.”

Even so, she was surprised when the Bulletin ran a survey in January asking the public to vote on the clock's time.

“A majority of our readers thought it should be one to two minutes to midnight,” she said. “We see North Korea testing its weapons, we see relations between the US and Russia deteriorating, there’s an arms race between India and Pakistan, there’s climate change … There’s a lot of fear, a lot of concern.”

ssubramanian@thenational.ae