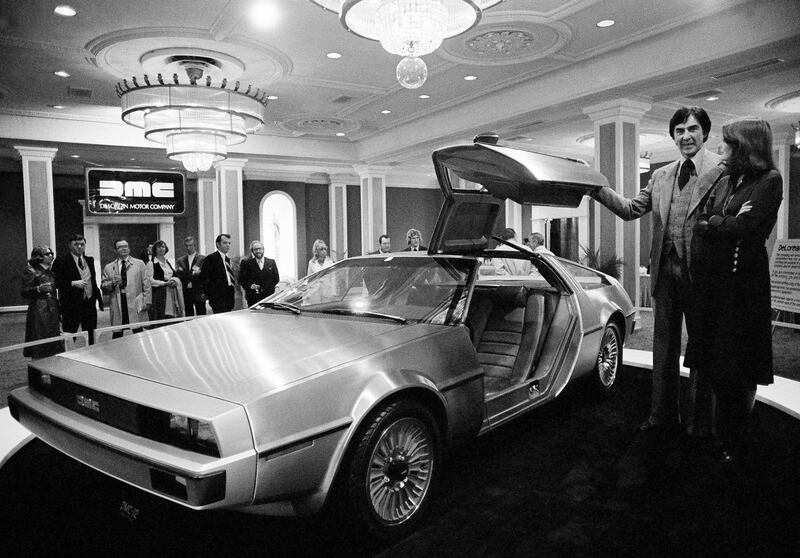

It was easy to fall for the DeLorean dream. The company's sleek sports car, the DMC-12, was built in Belfast. It had a wonderful stainless steel finish, gullwing doors and a stunning design. Its creator, John DeLorean, assured the British government pumping millions into his venture that this high-concept vehicle would create skilled jobs in Northern Ireland and conquer the lucrative US market. DeLorean was like a Hollywood star − tall, handsome in a grizzled kind of way, with a track record in the Detroit motor industry.

As a junior reporter for the BBC in Belfast back in the 1980s, I made films about the venture and interviewed DeLorean several times. I even got to drive a pre-production model around southern California. You, however, may have seen the DeLorean DMC-12 in the movie Back to the Future – but the chances are that you have never seen one on the road.

That’s because the DeLorean dream crashed headfirst into reality. First, the stainless steel bodywork was a nightmare, heavier than planned and difficult to maintain. Second, the engine was underpowered; it was not a very sporty sports car. Third, it was called the DMC-12 because the target price was an affordable $12,000 but ended up being $25,000 − roughly $70,000 in today’s money. Fourth, it was unreliable. When I drove the pre-production model on a TV shoot, the gullwing doors would not open, which was a huge embarrassment. Fifth, the money ran out. The British government lost millions and pulled the plug.

DeLorean’s failure meant a lot to me personally because, in those early reports, I interviewed US automotive experts who predicted more or less everything that went wrong. They said DeLorean was charismatic but had no real experience in the specialised sports car market. They said that the people of Belfast might be wonderful but that the area where the factory was located had no history of building cars and few workers with complex engineering experience. My work was attacked by those − including DeLorean himself − who desperately wanted the car to succeed. I did too but I was not prepared to believe a dream when all the facts suggested that it was never going to come true.

The reason this story comes to mind is that this is crunch week for the British government’s hopes for Brexit. The mistakes of the DeLorean dream are being repeated – all the exaggerated hopes, grand promises, bluster and the sad realities.

British Prime Minister Theresa May will meet EU leaders in Brussels on Wednesday to try to reach a deal. For the millions of decent people who voted for it, the Brexit dream was a bold corrective to many of the problems of contemporary Britain. The reality is that after two years of insistence that "everyone knew what they were voting for", the UK's Conservative government still cannot agree among itself what Brexit should look like.

The promises of independence, "easy" trade deals and a slightly different belief that Britain can go back to the future when it abandons the EU are just not happening. Mrs May could conceivably emerge from Brussels with some kind of deal, just as John DeLorean emerged from Belfast with some kind of car. But neither the deal nor the car resembled the dream people were promised. Mrs May's Brexit dream will cost billions more than we were told. It is underpowered with badly engineered parts and, for all but the most die-hard supporters, has already lost any shine it may have once had. Many Brexit enthusiasts no longer appear to be buying it.

The depressing truth is that those millions of people who voted for Brexit are absolutely right to want big changes in Britain. As the academics Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin rightly point out in their new book National Populism − The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, the UK's political and economic system is, for many people, broken. Politicians are widely distrusted and while Britain remains a rich country, many of its citizens suffer significant deprivation and fear a loss of identity.

However, Brexit is a symptom, not a cure. I am critical of the European Union but leaving will not in itself solve problems of inequality, social and cultural division and political disengagement.

On immigration – a key issue for many Brexit voters − the truth is that any deal that cuts the number of EU migrants might well increase the number from non-EU nations. On employment and trade, “taking back control” is the slick sales pitch but the reality is one of rising prices, disruptions to trade and jobs under threat.

Far from building trust, Mrs May risks cobbling together a deal no one really wants, further diminishing faith in her government and party while weakening business and making the country poorer.

The moral is clear. We should all have dreams but pursuing an impossible yet obsessive one in the face of all reality is a recipe for disaster. John DeLorean became so fixated upon his that he wound up bankrupt and was forced to sell his enormous estate to an American speculator named Donald Trump. DeLorean and Brexit tell a common story of ill-considered ideas, pursued at great expense, ultimately destined for the scrapheap.

Gavin Esler is a journalist, author and television presenter