BEIRUT // On paper, Beirut does not seem the kind of city where tens of millions of dollars would be invested in bringing art to the public.

But with the opening of two major museums this autumn, Lebanon’s capital has etched itself on to the art world’s map.

October saw the reopening of the renovated and expanded Sursock Museum after seven years, as well as the opening of Aishti Foundation, a museum funded by Lebanese retail mogul Tony Salame to exhibit his extensive private collection.

Within the space of weeks, Lebanon went from having no major art museums to having two.

But the latest additions arrive in a Beirut that has seen better days.

The country has been without a president for a year and a half. Rubbish is piled up on roadsides after the government failed to find a way to dispose of the country’s waste following the closure of Lebanon’s largest landfill in July. A double suicide bombing in mid-November reminded Beirutis that violence is never that far away.

But Beirut, ever the city of contradictions, pushes on amid the chaos.

As the Sursock Museum, housed in an ornate, century-old Beirut mansion, opened on October 8, a few hundred metres away the air was thick with tear gas and rocks as protesters upset with the ongoing rubbish crisis battled police. And as the Aishti Foundation opened its doors weeks later on October 25, parts of the capital were literally flooded with refuse as torrential rains swept away makeshift dumps.

“It’s quite symptomatic, it really represents what Lebanon is, with all the contradictions,” the director of Sursock Museum, Zeina Arida, said of the opening night.

“We questioned, of course – should we postpone [the opening]? But you never really have the best time here and we really had to open the museum,” she said, adding that many attendees that night were on their way to or from the clashes.

Reminders of Lebanon’s problems also line the route to the Aishti Foundation’s futuristic building just outside the capital. Driving from Beirut past the north-eastern edge of the city along a mostly industrial seaside road that is now home to its primary rubbish dumps, visitors must pass through the stench of refuse. Smaller piles of rubbish along the roadside have been set alight, and flies swarm on warmer days.

Mr Salame hopes his museum will provide an oasis to get away from this and all of Beirut’s other stresses.

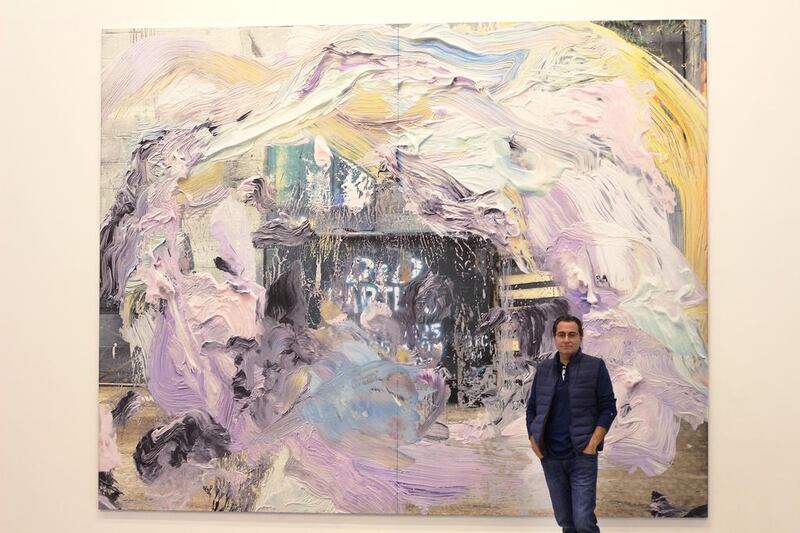

Overlooking Beirut’s skyline from the shore of the Mediterranean and tucked under a red metal exoskeleton, the Aishti complex is part luxury shopping mall and part art gallery. There are plans for a spa, restaurants, a “curated” bookshop and a rooftop bar.

The complex itself cost US$100 million (Dh367m) while the art in Mr Salame’s collection is believed to be worth many millions more.

“I like something in Dubai they came up with – they said build it and they will come. So we’re doing it,” said Mr Salame.

Art and retail dominate the complex, but Mr Salame thinks that they alone will not be the draw.

“The whole intention was to create a destination for well-being,” he said. “A place where you could relax and see art, where you can sit outside and be by the water ... Yoga classes by the water.

“It’s an example of how Beirut should be, of how Lebanon should be if we didn’t have all of those political tensions,” he said. “Maybe it’s a place where people can forget about the garbage, about the political problems, about the region – look at art, meditate, look at the sea. If it can help, that’s already a great thing, so our mission will be accomplished by creating this environment.”

While the Aishti project is unique in that it is an art space within a luxury shopping outlet, the Sursock museum stands out for having a collection made up entirely of works by Lebanese artists or artists who have lived in the country. Much of the collection was built up through the Salon d’Automne, an annual open call exhibition for local artists that the museum has held since its opening in 1961.

By focusing on Lebanese works, the museum hopes to promote artists who may have escaped broader attention and prompt explorations of identity in a country where history is still fluid and murky.

“Our history of art has been researched, but it has not yet been completely known or written,” said Ms Arida, the museum director. “It’s very important to understand, for society, where you came from.”

While the Sursock Museum has a long history, the museum today is totally different than the one that existed seven years ago.

The $15m renovation saw several floors dug under the mansion, tripling its space and providing room for temporary exhibitions, an auditorium, a research library, a restoration workshop and storage spaces.

The building’s original charm has been preserved in its exterior but the interior has been redone to be sleek and modern.

In a city where no public institution is dedicated to Lebanon’s violent and controversial modern history and where many old buildings have been levelled in favour of the city’s ever growing skyline, connections between the past and the present and questions about the city’s identity weigh heavy at the Sursock museum.

The museum hopes to address some of these issues through a public programme that includes historical walks, lectures on public space and gender and the transformation of Beirut, and workshops on writing, photography and even urban gardening.

“Art is also about ideas, it’s about history,” said Nora Razian, Sursock’s head of programmes and exhibitions. “I think what the museum’s public programme does is just allow people to engage with ideas, history etcetera in creative ways, in challenging ways, in fun ways. It’s a space that kind of bridges these different areas.”

foreign.desk@thenational.ae