In Germany’s Dresden, it was a statue of an open-armed woman looking over the ruined city. In Japan’s Hiroshima, it was the walls of a church, and in New York, it was steel beams of the World Trade Centre.

Those were iconic photos of parts left standing of obliterated structures after massive carnage.

The disaster at the Beirut port this week was not as deadly, but the explosion was huge and one strong building at its epicentre survived enough to make out what it was.

It is the grain silos building, the brainchild of Palestinian banker Yusuf Beidas, whose rise and fall as one of the world’s prominent businessmen in the 1960s was a defining chapter in Lebanon’s turbulent history.

Although 158 people died in the explosion and more than 5,000 were wounded, military specialists said the silos were crucial in shielding half of Beirut from greater destruction, in particular the heavily populated areas along the coast in the western part of the city.

“That building made a major difference. Without it the casualties could have been much worse,” said a Western security official, who has been looking into the explosion.

Beidas's Intra Bank empire collapsed in 1966, and Lebanon’s politicians divided large parts of its assets, marking new levels of dubious overreach in a system many Lebanese consider as failing them spectacularly today.

The once white silos appear to have taken the brunt of the explosion, limiting the damage to the Beirut Corniche and the mostly Muslim western half of the city.

See Beirut blast site and sunken ship from port side

The building’s concrete walls, facing east, collapsed and the ones facing west remained standing.

Retired lorry driver George Bassil, who used to transport supplies from the silos to mills in Beirut, said he grew up hearing how strong the 50-metre high structure was from his father, who had also worked there.

"I did not realise what he meant until I saw for myself. The silos were built correctly to take the pressure of the wheat and barley and corn inside it," Mr Bassil told The National. "They stopped the destruction from being far worse."

The silos were eventually funded by the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development and built after Beidas died in exile in Lucerne, Switzerland, in 1968. They had a capacity of 120,000 tonnes, or 10 per cent of Lebanon’s annual imports, before the explosion.

Beidas's son Marwan told The National that the silos were part of his father's drive to expand Beirut as the trading and financial centre of the Middle East.

“My father rarely went out after work, preferring to stay at home, and his friends came over there,” Marwan Beidas, who is in his 70s, said.

“But he greatly loved Beirut, and its hardworking, civil people. The decent people. Not the indecent politicians,” he said.

By the time a run on Intra forced the bank to halt paying its depositors in October 1966, the bank was the largest in the Middle East. It accounted for 40 per cent of deposits in Lebanon’s domestic banks.

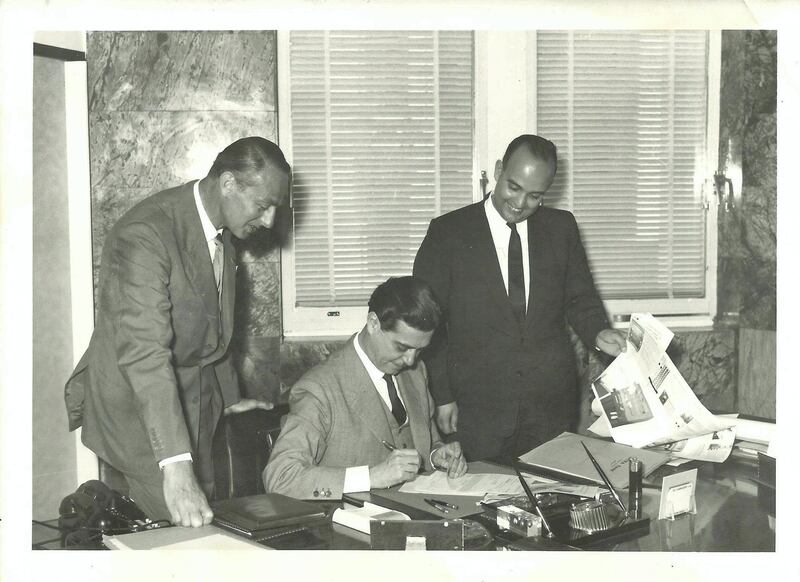

Beidas set up International Traders, whose Telex code was Intra, when he fled from Jerusalem to Beirut after the founding of Israel in 1948.

He was so tight with margins and meticulous with numbers that International Traders soon took over most of the currency exchange market in Lebanon, providing Beidas with the capital to set up Intra.

Beidas outflanked established Lebanese and Syrian families that had dominated banking in Beirut.

He focused on external expansion, and Intra soon had 40 branches abroad, amassing more petrodollar deposits than the competition, as well as from the Palestinian diaspora and the many Syrians who did not trust the Baathist rulers of their country.

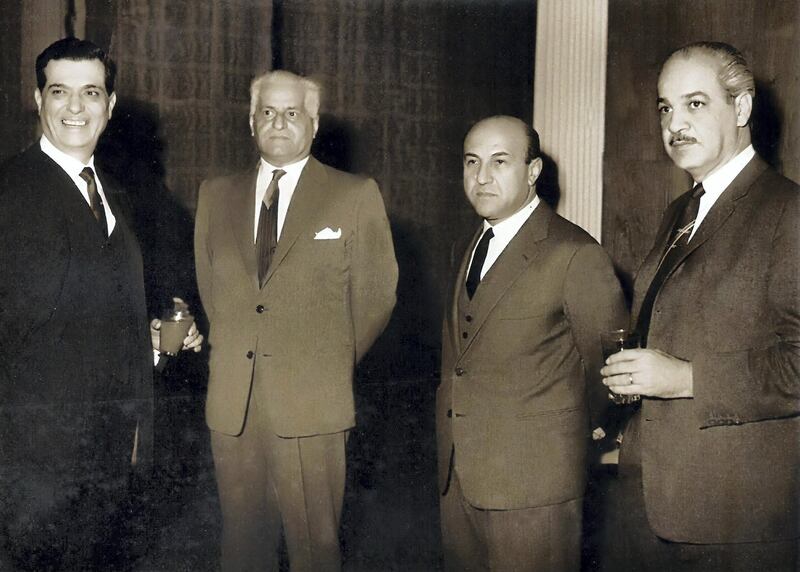

He rubbed shoulders with the who’s who of the East and West, from Charles de Gaulle, to Jamal Addel Nasser, and King Faisal of Saudi Arabia.

Intra owned a skyscraper on Fifth Avenue in New York, real estate on the Champs Elysee, Chantiers Navals de la Ciotat, one of France’s biggest shipyards, and assets across Europe and in Africa.

In Lebanon, Intra controlled Lebanon’s flagship Middle East Airlines, the famed Casino du Liban, and the Phoenicia Intercontinental Hotel, one of the world’s busiest hotels.

Another landmark was the Beirut port that the explosion engulfed last week. The port was run by Intra’s subsidiary, Cie de Gestion et d'Exploitation du Port de Beyrouth.

It may never be known what exactly prompted the run on Intra. A sharp increase in interest rates in Europe and the US may have prompted some big Saudi depositors to shift their money westward. Intra had also invested heavily in fixed assets and had a too-low of a liquidity ratio.

For disputed reasons, the then newly established central bank, Banque du Liban, did not provide enough cash to boost Intra’s liquidity, although Intra had no shortage of assets.

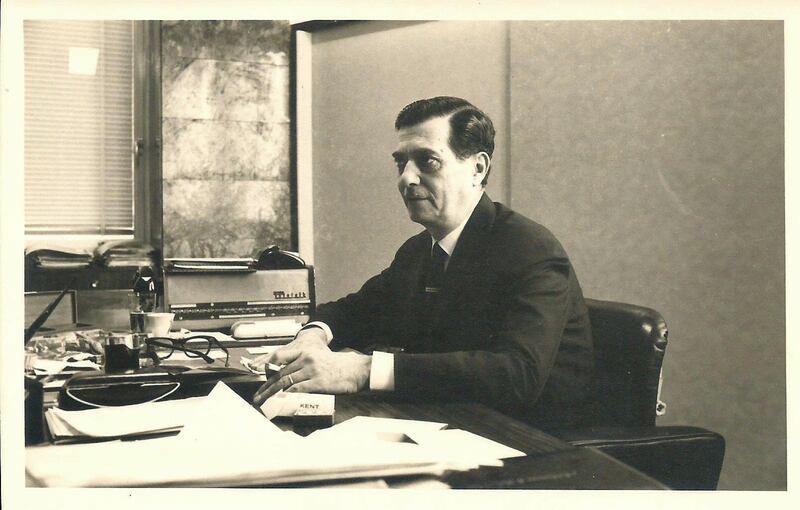

In an interview with Life Magazine in 1967, Beidas had a very low opinion in the Lebanese political class, and the Association of Banks in Lebanon, the same one that demonstrations overran on Saturday in Beirut.

He said his competitors “knifed him” and that he could not return to Lebanon because he would not be awarded the right to defend himself “freely and fully in a fair and open court”.

“No one can create a huge financial empire without some mistakes But I will not return to be gagged and jailed without trial, to be silenced – perhaps forever,” he said.

Marwan Bedas said that when the run on Intra started, his father was in Europe, and received a call from Yusuf Salameh, a late Palestinian-Lebanese merchant banker and writer, who headed Intra’s branch in New York.

Salameh, who was the brother of Wedad, Beidas’s wife, asked him what to do with $4 million that were in Beidas’s personal account in New York, Marwan said.

The $4 million in today’s money is equivalent to at least $32 million.

“My father instructed my uncle to transfer the $4m to Beirut, to pay the depositors. My uncle made the transfer, and the money later evaporated," he said.

In the Palestinian national psyche, Beidas embodied resilience.

He also became a symbol of the failure of Lebanon to turn into a melting pot as Michel Chiha, the Lebanese statesman who laid the foundations of the republic after independence in the 1940s, intended.

Chiha envisaged a country where anyone could rise in its laissez-faire system, provided the advancement was based on merit.

Even Beidas’s enemies did not dispute that the “genius from Jerusalem” was immensely qualified.

Five months before Intra collapsed, Lebanese publisher Kamel Mroueh was assassinated in his office, at the Al Hayat newspaper in Beirut.

Two men behind the assassinations, who served as enforcers for Jamal Abdel Nasser, were convicted. One was released, and the second escaped.

Mroueh’s son Kamel, who continued in the same line as his father, regards the killing of Mroueh as the day the rule of law collapsed in Lebanon, and the date to which the Lebanese civil war can be traced.

One of Beidas’s best friends, the late Lebanese business executive Najib Alamiudin, former chairman of Middle East airlines, said that the 1975-1990 civil war started with the collapse of Intra.

The two events marked immense failures in a system that were never remedied.

Beidas intended for the silos to become the nucleus of a regional distribution centre, capitalising on Beirut’s advantage in logistics, marketing and modern finance. Few, after his death at age 55, had an integrated vision for the economy of Lebanon, and the international connections to pursue it.

The silos did not fulfil their mission, becoming one of the few storage facilities in the country for domestic consumption. But they saved lives in a city with bittersweet memories for the man who had envisaged them, and who did not live long after his half-realised dreams were brought down.