MAZAR-E-SHARIF // Gunrunning here is a lucrative trade. The price of a Kalashnikov has quadrupled in parts of northern Afghanistan, driven up by the possibility of civil unrest as officials struggle to produce a result for August's presidential election.

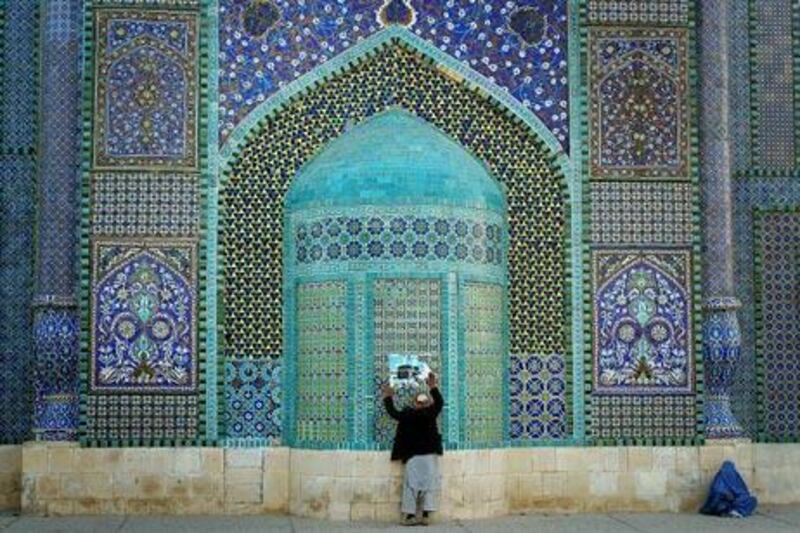

"The weapons business is good right now," said Gen Abdul Malek, a local warlord who fought briefly with the Taliban before double-crossing them and executing 2,000 of their followers. "Where it was once $150 for an AK-47 it has gone up to $600," he said. "Where it was five Afghanis" [about 10 cents] "for a bullet it is now 30." Mazar-e-Sharif, the cosmopolitan city that straddles international trading routes, shows little sign of the troubles that have swept northern Afghanistan this summer. But its open spaces and gentle hum belie the political and ethnic tensions threatening to divide the previously peaceful region.

Residents say rival warlords are squaring up, exploiting the political deadlock for personal gain at the same time as the Taliban makes rapid inroads across the north. "They exploit the misfortunes of people, using - the name of their tribe to incite violence and make money," a local journalist, who asked to remain anonymous, said. "People are saying 'Kill the Pashtuns'. The leader of the Pashtuns is saying 'Kill the Tajiks'."

The trouble started when the powerful governor of Balkh province, Atta Mohammed Noor, fell out with President Hamid Karzai after the latter overlooked him as his vice-presidential running mate. Instead, Mr Karzai chose one of Mr Atta's bitterest personal rivals, the warlord Marshal Qasim Fahim. Mr Atta threw his weight behind Mr Karzai's main challenger, Dr Abdullah Abdullah, campaigning energetically for him and festooning Mazar-e-Sharif with posters of a smiling Mr Abdullah. Billboards endorsing the president were defaced or torn down.

But now with Mr Karzai expected to win the election, possibly in one round, Mr Atta looks vulnerable. Old enemies have taken note. Trying to usurp him is Juma Khan Hamdard, a Karzai ally and governor of Paktia province in the east. Mr Atta and Mr Hamdard go back a long way: they fought with different factions during the civil war and later, as governor of a neighbouring province, Mr Hamdard was held responsible for the deaths of 12 people after his Pashtun-centric policies provoked riots.

The two men sit on different sides of the ethnic split: Mr Atta is a Tajik; Mr Hamdard belongs to the Pashtun ethnic group. Both have reputedly used ethnic prejudice to stir up their followers at times, and Mr Hamdard has even accused Mr Atta of having local Pashtun leaders assassinated. Mr Hamdard's spokesman denied suggestions that he was preying on ethnic insecurities. "Afghanistan is a house for all Afghans: Tajiks, Pashtuns, Hazaras, Uzbeks. And if you see the story of Balkh, it will tell you all Afghan tribes live together. Whoever tells you [otherwise] - it's completely wrong," he said.

Locals disagree. "As long as you have warlords in the government how can you have peace in the country?" said one. Mr Atta, meanwhile, has struck back at Mr Hamdard's attempts to undermine his authority. In a blistering speech he accused Mr Hamdard, in league with the ministry of the interior, of distributing weapons in order to destabilise the north. "Twenty-five commanders were given weapons by Juma Khan Hamdard in Charbolak, Chintral and Balkh districts. For each commander there were between five and 25 AK-47s, machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades and motorbikes," he said. At the same time Mr Atta defended the right of his own supporters to "peaceful demonstrations" against vote-rigging.

Some say that Mr Hamdard is a pawn in the plot, spurred on by government ministers unhappy with Mr Atta's defiance. The powerful interior minister, Hanif Atmar, is rumoured to be behind the campaign to discredit him. But either way, the fragmentation of the north is down to the central government's failure to impose itself. "The situation is declining faster and faster in the north," political analyst Haroun Mir said. "People can't rely on the Afghan security forces to provide protection. The absence of government authority [is creating the] tension."

Into the political vacuum have stepped the Taliban. Swathes of the countryside and sections of main highways have become impassable over the summer and previously safe Nato supply lines are under threat. The scale of the problem was highlighted when the German military called in an air strike that killed 30 civilians - the kind of incident associated with seemingly more volatile parts of the country. And then on Thursday Russia's ambassador to Afghanistan warned that Islamist militancy was spreading north into Central Asia. Although some insurgents may have come from the Taliban's strongholds in the south and east, most are local.

"The Taliban is a bunch of different groups using the same brand name," a security analyst explained. "The Taliban is essentially using a federal model. The Quetta Shura [the supreme Taliban council led by Mullah Omar in Pakistan's Quetta] lets them do their own thing ? which, by the way is where the government fails by being so centralised ? and ships in a few high-value assets ? Uzbeks, Chechens and so on."

The map of Taliban activity in the north roughly reflects the location of the Pashtun communities there. Kunduz province, where they have effectively opened a northern front against the German soldiers stationed there, has a number of districts with Pashtun majorities. Balkh too has Pashtun communities. "I see the calm before the storm," Gen Malek warned. "There will be violence and instability. There will be disagreements between the tribes."

Some observers struck a more cautious note, suggesting that while some districts might harbour insurgents, trouble would only occur on a large scale if international forces began targeting their leaders. "Then you have a lot of little guys scrambling for power. That would lead to chaos," the security analyst said. Meanwhile if Mr Atta is forced out of office he is unlikely to be out of power. During his five years as governor of Balkh he has consolidated up to 60 per cent of the province's business interests - particularly construction companies. Even if Mr Hamdard wins the governorship he covets, Mr Atta will informally continue to run things.

* The National