NEW DELHI // When Narendra "Bull" Kumar led an expedition in 1977 to a glacier high in the Karakoram mountains, he had little idea the trip would trigger a 34-year territorial dispute costing thousands of lives.

According to the US-demarcated map carried by the German team that recruited the mountaineer and Indian army colonel, the Siachen glacier was in Pakistan. Col Kumar believed this to be an error.

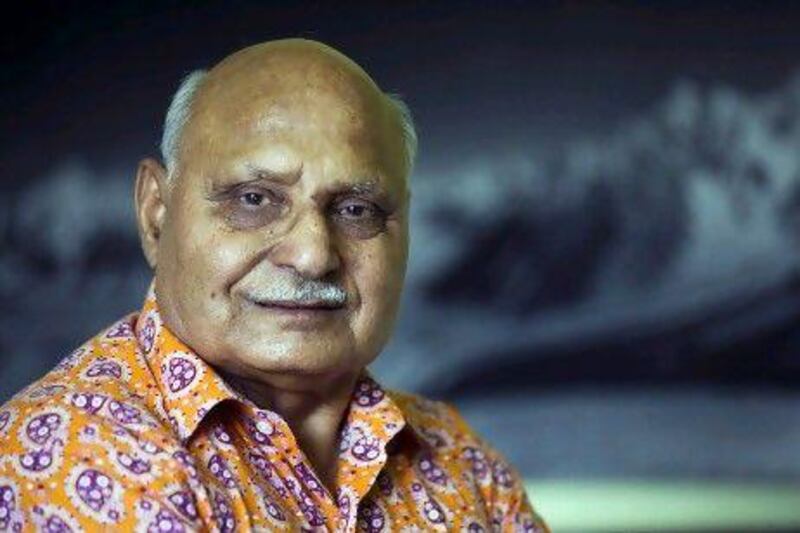

"I knew it was in India," Col Kumar, 78, recalled in an interview this week with The National. "All Indians knew that, but no one had noticed it on the international maps before."

By 1984, Siachen, the second-longest glacier outside of the polar regions, had become the world's highest battle ground.

Thousands of Pakistani and Indian soldiers have died in the dispute. Stationed on the ice 5,000 metres above sea level, the biggest danger for the troops was not the fighting. Most died from exposure, some perished in crevasses while others succumbed to altitude sickness.

After an avalanche killed 135 Pakistani soldiers and civilians in April, both sides have shown a will to remove their forces from the glacier that lies at the nexus between India, Pakistan and China in the disputed Kashmir region.

Negotiations are under way between Indian and Pakistan, but the latest round of talks in Pakistan ended last week without any agreement. Another round of talks to be held in India is planned for this year.

The origin of the conflict lies in an oversight contained in the Simla agreement which, in 1972, established the so-called "line of control" - the de facto border between Indian and Pakistan Kashmir.

The drafters of the agreement that separated Indian and Pakistani Kashmir - Indira Gandhi, India's prime minister, and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan's president - failed to divide ownership of the glacier, thinking its remote location meant it was of little value to either country.

While Col Kumar, who is now retired, believed it was Indian, Siachen's ownership had been left unclear.

In 1977, the highly decorated colonel was the head of the Indian military's high altitude warfare school and an experienced mountaineer. He lost four toes to frostbite while climbing Mount Everest. He earned the nickname "Bull" for his massive neck and boxing prowess in the military academy.

A year after the German expedition, he took a team of his students onto Siachen "for practical training". It was the first Indian expedition to climb onto the glacier and Col Kumar's real purpose was to reinforce India's claim to the glacier. The team, roped together, worked their way up from the glacier's snout. Temperatures fell to minus 50°C and their path was often blocked by gaping crevasses.

"There was nothing there except blue water, glaciers. No habitation. Nothing. It was beautiful," Col Kumar said.

But while they were enjoying the adventure, they had been spotted by the Pakistani military.

"Pakistani jets circled us, giving off plumes of coloured smoke. It was their way of saying: 'We know you are here.' We photographed that. People were scared, but we braved it out for the sake of the country."

The team also returned with rubbish they claimed was from the Pakistani side - buckets and other used materials bearing the Pakistani army's insignia. "That proved that they were climbing there, on to our side," said Col Kumar.

That military expedition kicked off counter-expeditions, which resulted in a race to stake out territory on the glacier.

"Before that, nobody cared for these abandoned areas covered in snow," said Col Kumar.

In April 1984, after a series of expeditions and counter-expeditions to stake claim to the glacier, India launched Operation Meghdoot (Cloud Messenger) to capture the Siachen glacier from the disputed Kashmir region. India had received intelligence that Pakistan was preparing to send troops to the glacier, and it rushed to send several hundred of its own their first. When the Pakistani troops arrived, they found about 300 Indian soldiers in control of most of the high points of the glaciers.

Brigadier Rajiv Williams led one of the most famous battles for control of the Siachen glacier.

"Imagine carrying an oxygen cylinder on your back and having not just to walk, but evading the enemy. It has a huge impact on your body and mind," said the retired Indian army officer in an interview. It was 1987, and Brig Williams was in command of 50 soldiers that captured a Pakistani post.

"It was minus 40 degrees Celsius at night, even in the summer months," said Brig Williams. "Evacuating bodies was very difficult. Sometimes we had to throw them from the top of a cliff. If we managed to get them into the helicopter, it would fly with the door open because the bodies didn't fit."

Food was not a top priority because of a lack of appetite at that altitude, he said. Instead, men who manned the post for six months at a time asked for supplies of kerosene for heat and more arms instead of rations.

There have been minor skirmishes since, but there has been no significant change in position between the Indian and Pakistani troops. India retains the high ground on the glacier, while Pakistan has set up camps at its base. A ceasefire has been in place since 2003.

Given the lack of fighting and the danger posed to the troops, Brig Williams questions whether it makes sense to have thousands of soldiers guard a barren piece of ice.

"It makes good sense to withdraw and go back to base positions and maintain a battalion," said Mr Williams, adding the area could be guarded with the use of satellites that can monitor border movement.

Another retired brigadier who served near the India-China border near Ladakh, and has been to the Indian base camp in Siachen, said "authentication of the border lines is essential" in trying to demilitarise the zone.

"The Indians don't trust Pakistan to agree to where the line" is, said Rumel Dahiya, the deputy director general of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses in New Delhi. The two sides must mark and exchange maps and agree the borders will not be moved, he said.

"That would give you a reason, if possible, if it changed, that it was an act of war," said Brig Dahiya. "But what is important to focus on is that we don't want war at that height."