NEW DELHI // Pressure from Tamil citizens is pushing India to back a United Nations resolution calling Sri Lanka to account for human-right violations, threatening diplomatic ties with its southern neighbour.

The US-led resolution to be discussed tomorrow at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva aims to hold the Sri Lankan government to account for the carnage that occurred in the last days of its 30-year war with Tamil separatists in 2009.

A UN panel last year said that 40,000 people were killed in the final months of the war. Hundreds of thousands were forced into camps as the government hunted down remaining members of the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

India, which has close relations with the island nation, initially refused to support the resolution when it was put forward last week, but uproar from its own Tamil population in the southern state of Tamil Nadu forced it to backtrack.

"We do not yet have the final text of resolution but I would like to say that we are inclined to vote in favour of [the] resolution," Prime Minister Manmohan Singh told the upper house of parliament on Tuesday.

His change of heart came after the DMK, a Tamil Nadu party, threatened to leave the ruling coalition over the issue. Already struggling to keep its fractious alliance together, the Congress-led government can ill-afford further discord.

The Sri Lankan government called its actions in this period a "humanitarian rescue operation" and has strongly objected to any international involvement in the reconciliation process.

But media reports have presented video footage of suspected Tamil militants being lined up and executed. A recent image from Britain's Channel 4 news appeared to show the 12-year-old son of LTTE leader Prabhakaran, shot five times in the chest at close range.

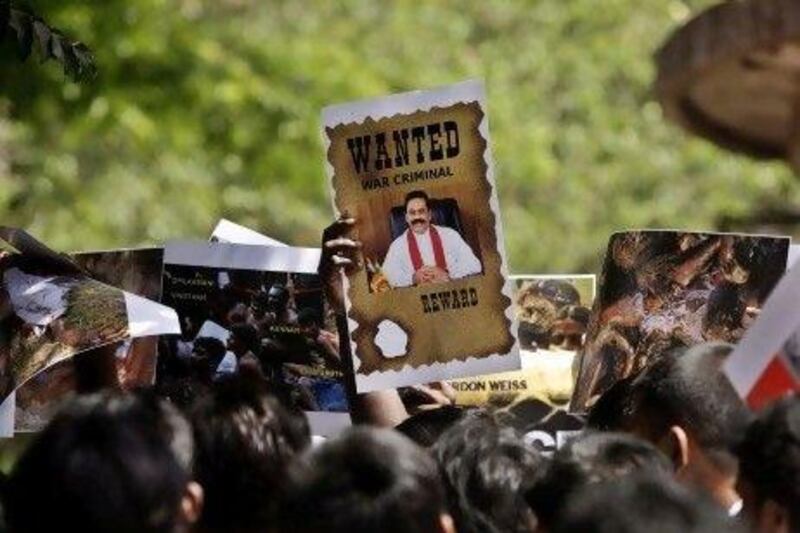

Tamil activists in India are pleased to see the government backing the resolution, which includes calls for investigations into extra-judicial killings and disappearances, and the devolution of powers to Tamil areas.

But they fear it may dilute some of its clauses, particularly plans for the UN to oversee the process.

"The resolution is already quite weak - if the Indian government manages to dilute it any further - it will be a huge betrayal," said Father Gaspar Raj, a Catholic priest from Tamil Nadu who ran a pro-Tamil radio station during the war.

He said many Tamil separatists would prefer to see the resolution defeated - leaving the door open for another, tougher resolution in the future.

"That would be better than a diluted version in which the accused are left free to investigate their own crimes," said Father Gaspar.

The issue has brought a rare political consensus to the fiercely competitive parties of Tamil Nadu, with even the local branch of the Congress party criticising the central government.

"Smaller groups in the past five years have been hijacking the pro-Tamil sentiment of these main political parties, so there is an element of political competition in these protests," said N Sathya Moorthy, a political analyst with the Observer Research Foundation in Chennai.

"But they also reflect genuine concern about the ethnic situation of the Sri Lankan Tamils among the people."

The issue will not have passed the attention of the home minister in Delhi, P Chidambaram, who represents a constituency in Tamil Nadu. He only just scraped to victory in the last general election of 2009.

"The local Congress party in Tamil Nadu knows it won't stand a chance in the 2014 election if it doesn't speak out strongly on this issue," said Father Gaspar.

With the LTTE banned in most western countries as a terrorist group, and its cadre decimated at the end of the war, human-rights investigations have become a last resort for Tamil activists.

But India is not a natural ally in the process. Its government once funded Tamil separatist groups in the 1980s but turned resolutely against them after the LTTE assassinated former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, husband of current Congress party president Sonia Gandhi, in 1991.

Nor does it want to encourage foreign prying in its own human-rights controversies, particularly in Kashmir where almost 3,000 bodies were found in unmarked graves last year. They are believed to stem from India's own battle against separatist militants in the region in the 1990s.

India has sought to build closer ties to Sri Lanka in recent years, building new schools, housing projects and railway lines - partly to check the mounting influence of China, which has benefited from the blind eye it turns to questions of human rights.

Many other countries, including Russia, Cuba and Zimbabwe, have stated their opposition to the US resolution, saying the text will have no effect without the consent of the concerned country.

[ foreign.desk@thenational.ae ]

Follow

The National

on

[ @TheNationalUAE ]

& Eric Randolph on

[ @EricWRandolph ]