BEIJING // For the past three months, Zheng Bojian's parents have rented a flat near his school in north-west Beijing. The 18-year-old needed a quiet place to study without wasting precious revision time commuting.

The stakes were high for Mr Zheng. Last week, he was one of 9.15 million high-school students that sat China's notorious gaokao examination that decides who will get a place at university - and who will not.

In a society that prides itself on valuing education, and where a university place is often seen as a way out of poverty, this puts great pressure on students.

Mr Zheng is hoping for a place studying medicine at Tsinghua, one of China's top two universities, and his programme of studying has been punishing, without a single evening off for a year. Usually, he said, he worked from 7.30am until midnight or 1am seven days a week, with breaks only for meals. "I felt exhausted but you get used to it," he said of his punishing schedule.

The efforts he and his parents made are not unusual in China.

State media recently published photographs of students apparently hooked up to intravenous drips in the hope that the amino acids they were said to be taking would help them study for longer into the night.

The gaokao involved four tests on Thursday and Friday, totalling nine hours, and covering mathematics, English, Chinese and liberal arts or sciences.

Only 6.85 million university places are on offer, meaning 25 per cent of those taking the exams will not get in. Liang Zheng, 18, from Beijing, who completed the gaokao on Friday, said: "It's very important for everyone. We only have one chance. We have expectations from other people and hopes for ourselves."

He added that he hopes to remain in his home city to study computer science.

The lack of emphasis given to school reports, coursework or other elements that could dilute the importance of the gaokao means that years of preparation count for little if a student has a bad day.

While some other countries, notably Turkey, have similar all-or-nothing school-leaving tests, the gaokao is "enormously stressful", said Mark Bray, a chair professor and director of the Comparative Education Research Centre at the University of Hong Kong.

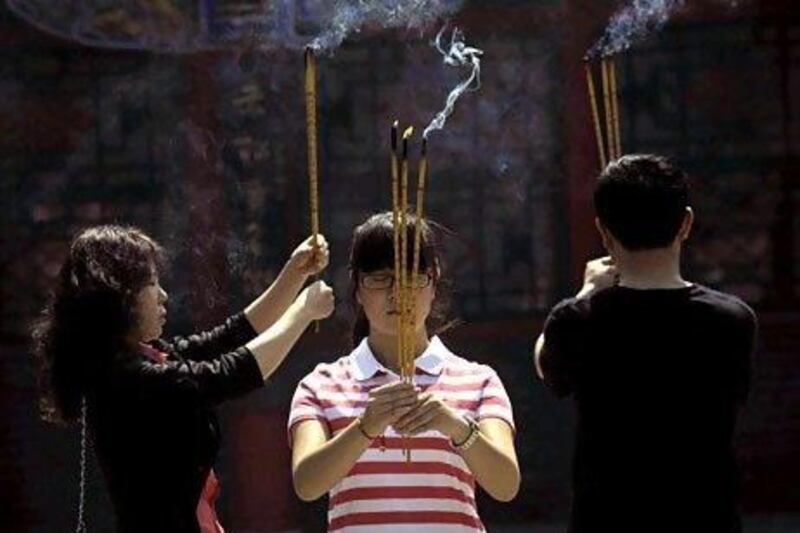

The gaokao is sometimes seen as placing as much of a burden on parents as on children, with a couple's hopes for a better future channelled into the efforts of what is typically their only child.

"For the parents, it's more stressful. We are anxious day and night," said Zheng Bojian's mother, who only gave her surname, Li.

Score of parents, many having taken the day off work, waited anxiously outside school gates for the exam to finish. On Friday afternoon, some presented their children with huge bouquets of flowers after they completed their final test and most had a camera to record the conclusion of what is seen as a potentially life-changing two days.

Yet, for all the demands, the gaokao is regarded as a level playing field, offering children from poorer backgrounds the chance to better themselves. It is unusually meritocratic for a country where more often "guanxi", or connections, determine success or failure. Even the students who have to endure the tests defend the system.

"It's the best way to select good students," says Wang Hanbing, who sat the gaokao at The High School Affiliated to Renmin University of China, where most students board for their final years.

Yet there is not absolute equality, even in the gaokao. Students in big cities are several times more likely to secure places at top universities than those in the provinces.

Some pupils living in Beijing, Shanghai or other metropolises, but born elsewhere, have to return to their home province to sit the exam, putting them at a disadvantage. Also, better-off parents can spend more on hiring private tutors, although even families where the main breadwinner has a modest income, such as from taxi driving, will still often pay for some extra lessons for their children.

"There's so much pressure that students feel that [regular] schooling is not enough, that they need to have extra tutoring. There's a huge parallel enterprise in shadow education," said Mr Bray.

"The central government in Beijing is concerned about the burden on children but families feel they cannot easily opt out. It's a competitive world."

Given the stakes, it is no surprise some try to cheat. According to state media, 1,500 people were arrested this year over the attempted sale or use of electronic devices, such as wireless signal receivers and clear plastic earphones, that would allow students to communicate with people outside the exam hall.

Although millions of students are destined to miss out on a university place, the situation is not as competitive as it once was.

Four years ago, only 57 per cent of the 10.5 million students who sat the exam gained university places.

There has been a gradual fall in the number taking the gaokao, partly because more Chinese school pupils are looking abroad for study opportunities. Often overseas institutions do not require the exam.

At the same time, the number of university places has risen, although the pressure to enter a top institution remains acute because graduates of less prestigious universities can struggle to secure fulfilling employment.

Now that the tests themselves are over, the gaokao students are faced with a two-week wait before they get their results.

While anxiety over the outcome remains, the worst is over. "There's no stress any more. We can do things we want to do now, such as play video games or musical instruments," Liang Zheng said with relief.