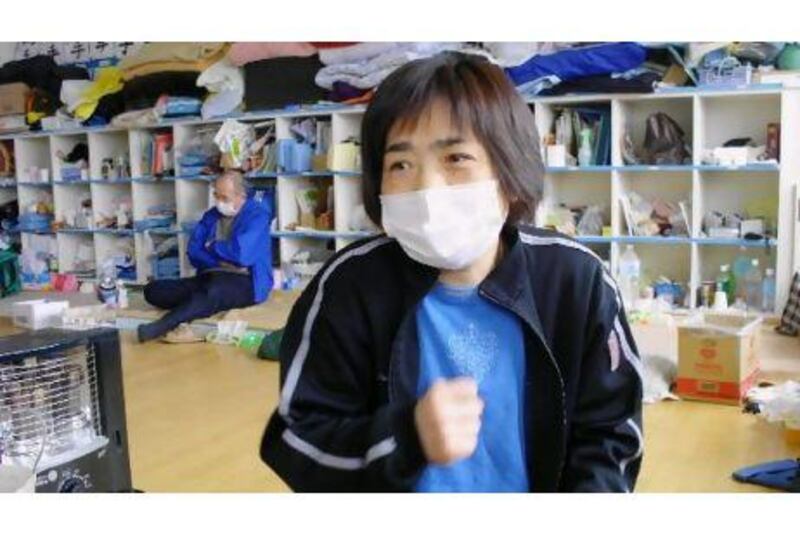

ISHINOMAKI, JAPAN // Sachie Tominaga still cannot believe what happened to her and her family a month ago. Before the earthquake and tsunami struck on March 11, she, her husband, her teenage son and her mother had a settled existence in this city in Miyagi prefecture on Japan's north-east coast.

Now, after floodwaters swept through nearly half the city, the family's house is uninhabitable and home is now a corner of a classroom in a primary school turned evacuation centre.

"I'd never experienced a big earthquake or big disaster, so I feel I'm still in a bad dream. I can't believe this is the real world," she said.

"I just want to go back to normal life. Not a luxurious life. Nothing special. Just normal daily life."

There is little chance of that happening soon for Mrs Tominaga and the 300 other evacuees remaining at Minato Elementary School. They are among about 17,000 people in Ishinomaki, out of the city's population of 163,000, who lost their homes. Numbers at the centre have thinned from the more than 1,000 who took refuge to start with, but for those that remain, many of them elderly, uncertainty clouds the future.

For the likes of the Tominaga family, moving back home is impossible and there are no relatives to take them in. The ground floor of their house was wrecked, and the rest is unsafe. The only option is demolition.

For all the adversity the family faces, it could have been much worse, as 2,600 in the city died and 2,800 remain missing. The death toll nationwide now exceeds 13,000 and more than 15,000 are missing.

Mr Tominaga was saved because the construction company where he works is based in an area of higher ground and it was easy for him and his colleagues to move higher still, although it was two days before he was reunited with his family. Mrs Tominaga rushed to the family home, where her mother and son were, and travelled with them by taxi to the school. She took the taxi back home, ensured the power was turned off, and this time chose to head to the school on foot. It was a decision that probably saved her life. Many of those who tried to escape by car died when the roads became packed with traffic and cars were swept away by the floodwaters.

"There was a traffic jam. I was lucky," she said. "After 10 minutes or 15 minutes [at the evacuation centre] the tsunami moved here. That's what I heard from the other people. I had no sense of time. I was panicking. It was scary. I tried not to watch anything.

"At that time I could only think about my family. Afterwards I heard some friends had died or were missing. I was lucky because all my family are still alive."

While Mr Tominaga has recently been able to go back to work, where the family will live in future remains uncertain. The children may arrive back at the school soon and that could mean the evacuees will be moved, although they have yet to find out where.

"I don't know where we'll go. The number of temporary houses is much less than the number of people who want to move in," she said.

"I'd like to get back to the peaceful life I was living before the earthquake, but I am not sure that will happen in 10 years."

On the first floor corridor, there is a pile of forms for evacuees to fill in if they want to apply for assistance. Many are looking to move into the temporary housing which is now being built in another part of town.

Each classroom on the second, third and fourth floors of the evacuation centre houses between a dozen and 20 evacuees, the rooms immaculately tidy with families lined up alongside one another. People from the same neighbourhood are mostly staying with one another.

"Most people kind of know each other, so they can find common topics, such as talking about their situation," said Keigo Abe, 63, who used to run a welfare centre and is now an evacuee at the school. He acts as his room's representative, attending a daily meeting at the centre's office where requests for assistance, such as for particular relief items, can be made.

In the morning, a women walks around ringing a bell and calling on each room to let them know boxes of supplies have arrived. Evacuees rush down to the school's gymnasium and a frenzied few minutes follow in which they search through boxes of clothes, toiletries and other donated items, hoping to add to the meagre tally of possessions the tsunami left them with. Hot food and relief items are provided by volunteers from non-governmental organisations such as Humanity First and Peace Boat, and staff from the Red Cross provide medical care.

"It's getting much better. Generally people are getting more relief items compared to a couple of weeks ago," said one evacuation centre resident, Shigeko Nakamura, 65, as she clutched the first bag of nappies she had been able to collect for her one-year-old grandson since the tsunami.

The ground floor of the building is where stores of some relief items are kept, and here a brown tide mark left by the tsunami waters is visible just beneath the ceiling. In one room, the clock is stopped at 3.50pm - the time power was knocked out by the floods.

Shadi Ghanim's cartoon, page a18

Qatar sends extra gas shipments to Japan, page b1