JAIPUR // There is a new date on the international glamset's calendar: the third week of January, Jaipur, India. It is standing room only at the Jaipur Literature Festival, now in its fifth year. Students, film stars, authors and poets spill out into hallways, while the Daily Beast editor, Tina Brown, does the rounds on the front lawn in a little black dress and sunglasses. The US ambassador grins hard at anyone who looks him in the eye, and the Queen of Bhutan regales listeners with tales of leaving her country for the first time as a six-year-old, strapped to a mule.

"There's nothing else like this," said William Dalrymple, the festival's organiser and a celebrated author. "We don't have an office and we can't afford to advertise. So it's all word of mouth." Ribbons, fireworks and raucous parties are obviously a winning combination for books in India. The festival began on Thursday with a party on the front lawn attended by international authors such as Alexander McCall Smith, the Bollywood royalty Om Puri and Gulzar along with the fashion designers Brigid Keenan, as well as Bina and Malani Ramani.

They are just some of more than 25,000 people expected to attend this year, along with 190 authors - quite the improvement from the first year, when a few dozen people came to hear 18 authors speak, two of whom did not show up. The setting is a former maharajah's palace with haphazard blue trim, expansive lawns and a couple of peacocks. Jaipur is one of India's most attractive cities, its majestic forts and pink palaces emerging from a gloomy January fog that grounded some authors in New Delhi, including the Nobel Prize laureate Wole Soyinka, and played havoc with the agenda.

If the crowd is eclectic, the agenda is surely more so. The big item this year is the Dalit writers, who are saying some uncomfortable things about class Hinduism. There are also biographers apologising for their craft, and serious journalists debunking conspiracy theorists. The oddest thing, however, is to see Booker Prize authors and big name celebrities chumming around with the unpublished quotidian masses, including dozens of schoolchildren and students.

"It's completely egalitarian," said Mr Dalrymple. "There's no VIP room. So yes, it's a glamfest but equally we've got schoolkids from Jaipur, we've got unpublished poets from Bihar, we've got Bengali political activists and lots of Dalits have showed up this year to support their authors." The Dalits, or untouchables, are speaking out about the continuation of the caste system in the villages, a sensitive subject in India - one that made it on to the agenda "not for PC reasons but because the work is fantastically good", said Mr Dalrymple.

Speaking through an interpreter, the author S Anand said urban elites probably did not realise the caste system was an apartheid in many Indian villages, where Dalits must build their houses to the west, downstream, near the gutters. "There is a physicality to the oppression," he said. Amish Mulmi, a Nepalese writer of short fiction, said he was more concerned about the status of English itself in the subcontinent. Ever since Salman Rushdie shook up the literary world in the 1980s with his Satanic Verses, India has carved its own path to the heart of the English language, building a body of literature that easily leapfrogs any lingering postcolonial sensitivities. That does not mean, however, that all the cultural dissonance of writing in a language that originated somewhere other than your homeland has disappeared.

"We tend to glamourise English writing," said Mr Mulmi. "I am from Nepal and my group of friends, we have all studied abroad and there is a sense of alienation about what Nepalese literature is all about. There's a sense that if you learn English and read and write it, you're better than other people." If English is your mother tongue, if it is the language you think and dream in, how can you not write in it? asked Deepika Arvind, an Indian poet and journalist. "For large populations in the urban centres, English is the language that you think in, so of course you write in it, too."

It is far more important to remain authentic, she said, so an entirely unique and independent body of Indian literature should come as no surprise. "We have our own traditions, and they have always been far ahead of everyone else, far ahead of their time, from Sufism onwards," said Ms Arvind. "I don't see why I should write about the earth and the rain and the village. I'm going to write about the city, load-shedding and Facebook - That is who I am, I can't fake it."

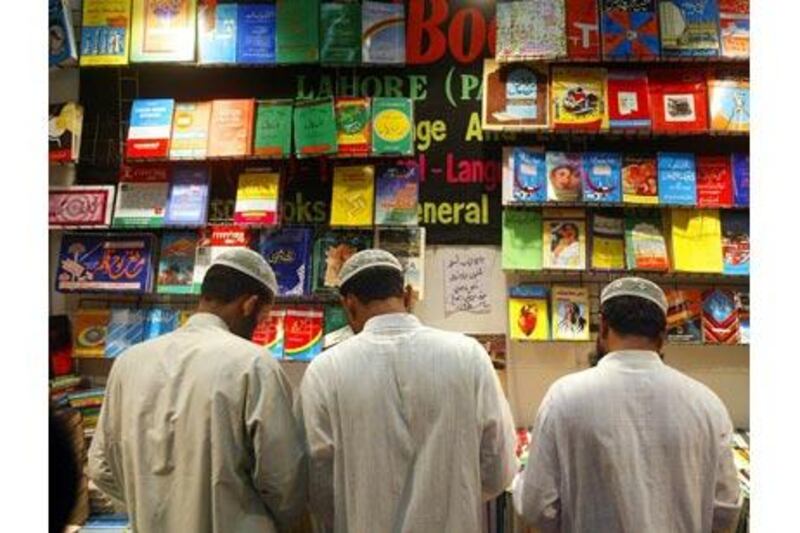

A recent survey by the English language news magazine Tehelka suggested Mr Mulmi might be on to something, however. It showed that most Indians read English books mainly for career advancement, or to improve their English. Only 18 per cent reported reading English for pleasure. Even so, most Indians buy two books per month, although readers in Delhi and Mumbai spend the least and readers in Thiruvanthapuram, the land of call centres, spend the most. That same sense of urgency and optimism attracted large groups of children and students to the festival. A group of engineering students said studying from 8am to 6pm six days a week left little time for books, but they did not doubt the importance of reading to their future success.

"I would like to go abroad, going outside to gain knowledge is good, but I want to be in India, one student said. "The future here is very bright." Ultimately, the festival is one big party, a good one, where anyone who likes books is invited to a beautiful place to hear authors talk. Mr Dalrymple said it was "lovely" to enjoy such sudden success, but the Diggi Palace Hotel has its limits. If numbers keep rising, the venue will not change - but a trek into a nearby five-acre field may soon be necessary.

It probably should have happened this year "but we wanted to keep it buzzy and tight and exciting rather than spread ourselves out". * The National