NEW DELHI // The dairy cooperative that Verghese Kurien built in the dusty town of Anand, in Gujarat, has gone from a daily production of a few hundred litres of milk in 1949 to nine million litres today.

A materials engineer by training, Kurien stumbled by accident into the world of milk cooperatives, in the process becoming the architect of the White Revolution, which made India the world's largest producer of milk.

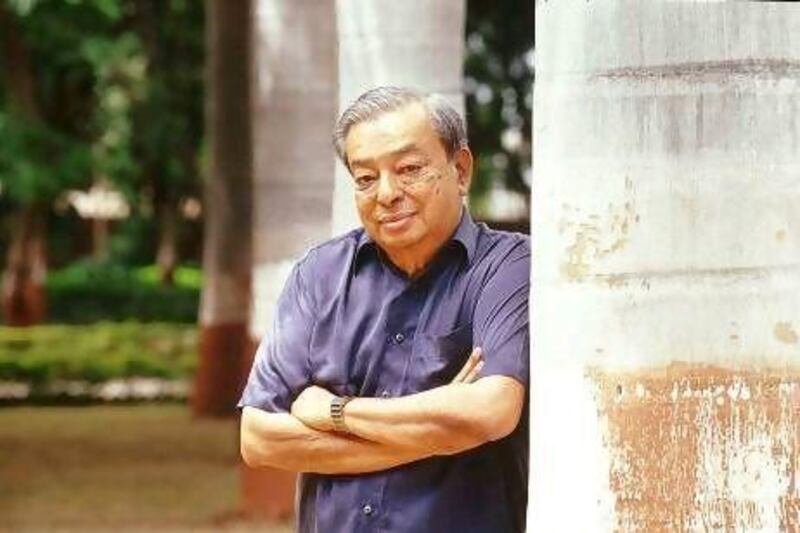

Kurien, who was dubbed ''The Milkman of India,'' died yesterday at the age of 90. He leaves his wife Molly and daughter Nirmala.

In a message of condolence, the Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh,hailed Kurien as "an outstanding and innovative manager and an exceptional human being. His contribution to the welfare of the farmer,and agricultural production and development of the country is immeasurable".

The Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) is now an 120-billion-rupee company (Dh7.9bn), and its leading brand Amul is virtually a synonym for milk and butter in India. It employs nearly 3 million farmers in 16,000 villages across Gujarat.

The success of Kurien's cooperative not only provided a model for others around the country but also carried symbolic heft, showing for the first time that a newly independent India could produce enough milk for its population.

India, which used to produce about 20 million tonnes of milk every year in the 1960s, now produces nearly 122 million tonnes.

Born in 1921 in the town of Calicut, now Kozhikode in Kerala, Kurien studied physics and mechanical engineering in universities in India and in the United States.

On his return to India, he was sent by the government to one of its dairy research labs in Anand, where a ragtag cooperative of farmers was attempting to free itself of the "clutches of self-serving middlemen", as Kurien described it in a recent book titled Amul's India.

Ruth Heredia, in her book The Amul India Story, describes how Kurien itched to leave Anand for many months after he got there. He nearly succeeded once in decamping to Bombay (now Mumbai) until he was buttonholed, just before he boarded his train, by the founder of the fledgling union of farmers.

Organising the union proved to be a monumental challenge, and there was, Kurien wrote in an essay in Seminar magazine in 2001, "no dearth of cynics". Could 'natives' handle sophisticated dairy equipment? Could western-style milk products be processed from buffalo milk? Could a humble farmers' cooperative market butter and cheese to urban consumers?"

With the right technology, Kurien proved, this was possible. So committed was he to technology that when Rajendra Prasad, the Indian president in 1950, toured the cooperative's plant and inspected a shiny new veterinary van, he exclaimed: "In Bihar we don't have anything like this even for humans! Yet you have it for your cattle!"

Kurien strongly believed "that by placing technology and professional management in the hands of the farmers, the living standards of millions of rural poor could be improved," RS Sodhi, managing director of GCMMF, said yesterday.

The cooperative movement empowered India's farmers, even though each individual farmer's output was meagre.

The success of Amul prompted then-prime minister Lal Bahadur Shastri to set up the National Dairy Development Board in 1965, headed by Kurien, to repeat the Amul model across India. Shastri based the board in Anand, Kurien's own little town.

Operation Flood, undertaken in 1970 by the board and Kurien, went on to make India the largest producer of milk in the world.

"Verghese Kurien was a fearless man," Rahul daCunha, the creative head of daCunha Communications, which has created Amul's advertising campaigns for 46 years, said yesterday.

"No one and no situation deterred him. He was blessed with a wicked sense of humour. It's a great loss."

Kurien remained chairman of the dairy board until 1998 and of the GCMMF until 2006. He left the latter post after disagreements with its management, telling the media at the time that the cooperative's board "has only become a pawn in the bigger game plan of some vested interests bent upon capturing [control of] the cooperative body, which has withstood many such attempts in the past".

Amul was, Kurien believed, about more than just milk. In some ways, when it began, it was even a miniature replica of the struggle for independence that India had just won.

"It was the producers' struggle for command over the resources that they create, a struggle to obtain equitable returns," Kurien wrote. "It was a struggle against exploitation. A refusal to be cowed down in the face of what others believed to be the impossible."

[ ssubramanian@thenational.ae ]

Follow

The National

on

[ @TheNationalUAE ]

& Samanth Subramanian on

[ @Samanth_S ]