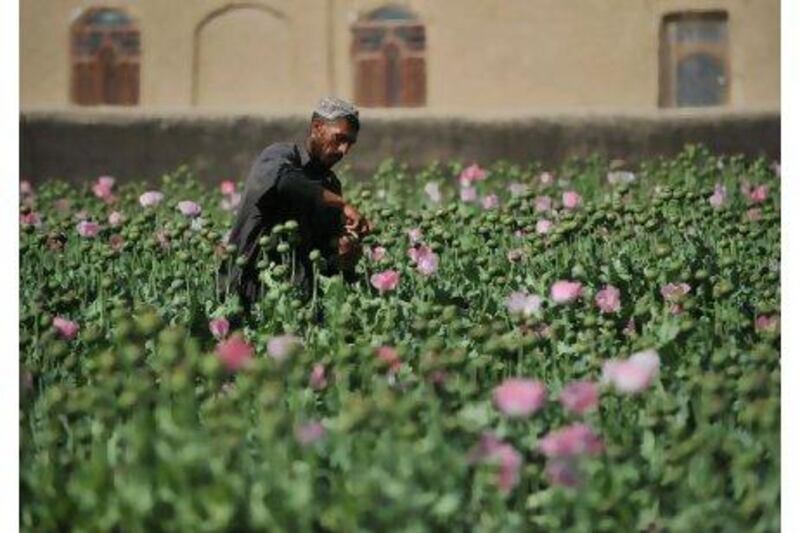

KABUL // Taliban insurgents are focusing their efforts on harvesting this year's opium poppy crop in southern Afghanistan, delaying the launch of the spring offensive they announced against Afghan and Nato troops last month.

The Taliban declared the start of a spring and summer fighting season on May 1, promising to attack military bases and government institutions as Nato prepares to hand over security to Afghan forces in July.

But in Taliban strongholds in Helmand, Kandahar and Uruzgan provinces, insurgents are laying down their arms to help cull the lucrative crop, which yields the sticky opium paste used to make heroin.

It earns the Afghanistan's Taliban, about US$300 million (Dh1.1bn) in profit each year, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC). The entire Afghan opium industry is worth approximately $3bn, and what profits are not claimed by the Taliban go to farmers, tribal warlords and drug traffickers.

Mohammed Uthman, a former Taliban commander in poppy-heavy Uruzgan province, said: "Everything is calm right now because the Taliban are busy with the [poppy] crop." More than 73 square kilometres of the poppy were planted in the province last year, the UN reported in its Winter Opium Rapid Assessment Survey released earlier this month.

"The weather is warm but the fighters are concentrating on the harvest rather than the fighting," Mr Uthman said. "Once they are finished, they will begin their operations."

Despite the poppy harvest, the Taliban have still carried out several high-profile attacks against government institutions so far this spring. Earlier this month, at least 35 Afghan construction workers were killed after an hours-long ambush by Taliban fighters on their compound in eastern Paktia province.

Nearly 200 foreign troops have been killed in the conflict this year, as the Taliban seek to undermine security gains ahead of the foreign troop pull-out. The UN reports that 2,777 civilians were killed in Afghanistan last year.

But military analysts and residents in the south say the full wrath of an emboldened Taliban insurgency has yet to be felt.

Once the labour-intensive harvest, which lasts from the beginning of May to mid-June in some areas, is finished, Taliban fighters will not only be free to again pick up their weapons, but will also be flush with cash to purchase new ones.

Poppy seeds are normally planted in the fall, after which the crop's vibrant flower petals drop off to reveal a thick milky sap - this is opium in its purest form.

Khoshal Khan, a local militia commander in Uruzgan's provincial capital Tarin Kowt, who has extensive knowledge of Taliban operations, said: "Local Taliban have their own poppy fields that they harvest to fund the war. But people living under Taliban control also give a portion of their poppy to the fighters. They use the money to buy weapons and to feed their fighters."

Because of the fluid and complex nature of the insurgency, it is unclear how many of the nearly 30,000 insurgents, according to one US government estimate, are being diverted from the battlefield to the poppy fields. Taliban spokesmen declined to comment on their movement's involvement with the crop.

But Mr Uthman, who until 2008 commanded up to 40 Taliban fighters in Uruzgan, says at least 30 of his troops were also farmers. Across the south, Mr Uthman estimates, 70 out of every 100 fighters are farmers, the majority of whom grow poppy.

The UNODC says about 250,000 Afghan families - or six per cent of the population - are involved in culling the poppy crop across the country. Thousands more are involved in refining and smuggling it across Afghanistan's volatile and poorly guarded borders.

Jeremy Milsom, a counter-narcotics officer at the UNODC office in Kabul, said: "Illicit drugs are all pervasive in this society. And because Afghanistan is such a large producer [of opium], it ends up affecting the society in many ways and on many levels. It draws people into crime and into the bigger conflict that comes with that."

Last year, blight wiped out much of Afghanistan's opium harvest, sending prices rocketing by nearly 300 per cent this year, according to the UN.

In the south, where the Taliban insurgency is the strongest and the rate of poppy cultivation is the highest, opium is selling for as much as $195 (Dh716) a kilogram, up from just $53 last year.

In Helmand, more than 650 square kilometres of poppy were planted in this year's harvest. In Helmand's neighbouring province, Kandahar, the Taliban's spiritual homeland, nearly 260 square kilometres were planted, according to this month's UN opium report.

While the number of square kilometres planted in Helmand and Kandahar was down slightly from last year, the UNODC, in its biannual report on the Afghan opium industry released last week, says there is a "clear association between insecurity and poppy cultivation".

"Almost all villages in insecure areas had a high probability of cultivating poppy," the report said.

Violence and insecurity are at some of their highest levels since the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, and poppy has reappeared as the crop of choice in several provinces where it was previously eradicated.

Just 12 of Afghanistan's 34 provinces are expected to poppy-free this year, according to the UN. "All I can say at this stage is that we're worried," UNODC's Mr Milsom said.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae