Pakistan praised Saving Face, a documentary about women disfigured by acid attacks, after it won an Oscar in February. But the film may never be shown there as its subjects have launched a court battle to stop its release, fearing reprisals. Zeeshan Haider reports from Islamabad

It is barely three months since Pakistan's first Oscar winner triumphantly brandished the coveted golden statue with the words: "All the women in Pakistan working for change, don't give up on your dreams, this one is for you."

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy had just accepted the Academy Award for Best Documentary Short for Saving Face, a harrowing yet uplifting account of female acid-attack victims.

Copies of the film were presented to Hollywood stars such as George Clooney and Brad Pitt, with Saving Face and the issues it raised seemingly set for an international audience.

Plaudits came thick and fast. Ms Obaid-Chinoy was awarded Pakistan's highest civil award, while Angelina Jolie wrote a commentary about her for Time magazine's "100 Most Influential People" list.

Pakistan's president, Asif Ali Zardari, applauded the 33-year-old filmmaker for "bringing laurels to the country ... and sending a message to the world".

Yet while Ms Obaid-Chinoy's Oscar acceptance speech was broadcast on Pakistani television, it seems her documentary may never be seen in the country of her birth.

The opposition has come from a surprising source - some of the female survivors of the acid attacks, who are threatening legal action to prevent the film being seen by their neighbours and families.

Mohammed Khan, the director of the Acid Survivors Federation Pakistan (ASF), claims the women "thought this film [was] for international audiences, and that's why they appeared in the film. They had no idea that it [would] be shown in Pakistan as well".

His organisation helped in the making of the documentary but Mr Khan said the women face a backlash and reprisals in their male-dominated communities.

"You are well aware of the society and you know what will happen if a film showing a girl who has suffered acid attack is seen in her village," he said.

Saving Face chronicles the work of Dr Mohammad Jawad, a British-Pakistani plastic surgeon who travels to Pakistan to carry out reconstructive surgery on women who have been disfigured by acid attacks. The 42-minute film is dedicated in part to two of these women from Punjab province, Rukhsana, 23, and Zakia, 39, who both agreed to be filmed.

Rukhsana's husband threw acid on her after she refused to live with him. Her sister-in-law poured petrol on her, while her mother-in-law lit a match to set her on fire.

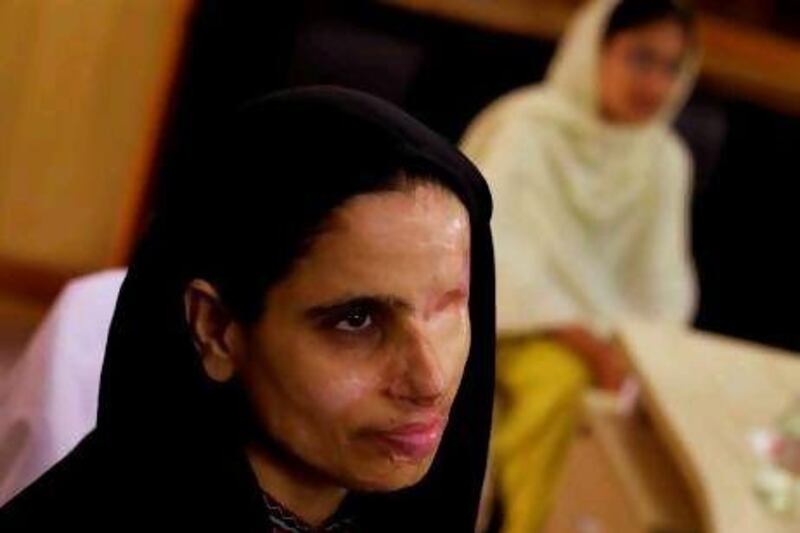

One of those seeking to block the film's release in Pakistan is Naila Farhat, who makes a brief appearance in the documentary.

At 13 she was left blind in one eye after a man she refused to marry threw acid in her face as she walked home from Independence Day celebrations.

Now 22 and training as a nurse, Ms Farhat says showing Saving Face in her home country would be "disrespectful to my family, to my relatives, and they'll make an issue of it".

She fears the film could put her and the other women in danger.

"We're scared that, God forbid, we could face the same type of incident again. We do not want to show our faces to the world," she said.

Ms Obaid-Chinoy, a Canadian-Pakistani, and her co-director, Daniel Junge, had hoped to use the film as a launch pad for a campaign to create wider awareness of the problem of acid attacks in Pakistan, and mobilise action against it.

The filmmakers had planned to screen Saving Face at colleges and universities across the country.

The documentary has already been shown on the cable channel HBO in North America and by Britain's Channel 4.

According to Naveed Muzaffarar Khan, the lawyer representing the ASF and six of the women, a case has been filed at the Islamabad district court, which restrains the filmmakers until the case is decided. The next hearing will be on June 6.

Mr Muzaffarar Khan claims that none of the women consented for the film to get a public release in their home country, and that the objection of just one would be sufficient to block it.

"The survivors are opposed to the screening of the film in Pakistan because they are facing threats," he said. "They all come from conservative communities."

He told the AFP news agency that the victims "were absolutely clear in their mind in not allowing any public screening, as that would jeopardise their life in Pakistan and make it difficult for them to continue to live in their villages".

The ASF's Mohammed Khan said his organisation does not "want to blow this issue out of proportions but, of course, we will go to court if they did not come to any agreement that bars its screening in Pakistan".

In reply, the filmmakers insist that they obtained full written permission from all the women, including Ms Farhat, for a global release that also covered Pakistan.

Mr Junge has described the allegations as "false", adding: "We had great plans to both screenings and broadcast in Pakistan but currently all plans are on hold.

"One person - the film's principal subject, Zakia - initially asked that we not show the film in Pakistan but has since given permission, in writing, to do so, so long as we make a few edits for the family's safety, which we have done."

Mr Junge said he and Ms Obaid-Chinoy were concerned at the safety of their subjects, but added: "If the film does not ultimately get released in its home country, this will be unfortunate for all those who wanted the message to be out, and for potential future acid victims."

Officials estimate that there are about 150 cases involving acid every year. Women's-rights groups put the figure much higher, with many cases unreported in rural areas where feudal and tribal customs hold sway.

Disfiguring acid attacks are a major weapon of domestic violence in Pakistan, with male relatives or in-laws seeking to "punish" female relatives they believe have damaged the "honour" of a family over issues that can include them marrying a man without their consent.

In March, Fakhra Yunus, a former dancer who was badly mutilated in an acid attack 13 year earlier, allegedly carried out by her husband, committed suicide by jumping from the roof of a clinic in Italy where she was being treated.

Last year, legislation was passed to tackle the problem. The Acid Control and Acid Crime Prevention Act allows courts to impose prison sentences from 14 years to life, along with a fine of 1 million rupees (Dh40,000).

But many of the accused escape punishment, either by intimidating the families of victims or by using their influence to weaken the presentation of cases in court.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae