BANGKOK // Thousands of people will join mass protests outside Myanmar's embassies across the world today to draw attention to the tragic events in Yangon 20 years ago when the army crushed a pro-democracy uprising, killing thousands of protesters. "The spirit of 8/8/88 must never be allowed to die," said Zin Linn, who took part in the protests in 1988 and who is now a leading spokesman for the exiled opposition.

Among those expected to join today's protests is Mia Farrow, the actress, who will speak out against the continued detention of hundreds of political dissidents, including Aung San Suu Kyi, the opposition leader who has been under house arrest for much of the past 19 years, the first stint starting shortly after the events of 1988. Although there had been sporadic street protests throughout that year against military rule and economic mismanagement, the mass demonstration called for Aug 8 marked a major turning point for the pro- democracy movement in Myanmar.

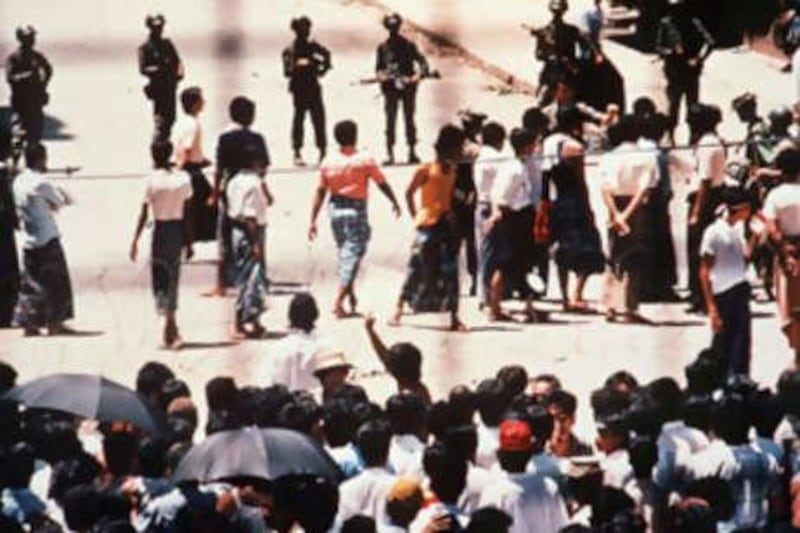

The date was chosen because it was meant to be auspicious - a reflection of the deep-rooted superstition that grips almost all of Myanmar, including the country's generals. Hundreds of thousands of students, civil servants and monks marched through Yangon - then the capital - calling for democracy and an end to military rule. The protests brought Myanmar to a standstill for weeks, and threatened to topple the country's one-party state. The universities had been shut several months earlier after starting the first protests.

"We felt that there was no justice or freedom. So we decided we had to bring about an uprising that would end single-party rule," said Aung Din, one of the protest leaders, now in exile in the United States. "We called for 'democracy', but none of us knew what it meant at the time," said Aung Naing Oo, another student activist, now in exile in Thailand. "We had to look it up in the dictionary - but we knew we wanted freedom and an end to military repression."

Six weeks after the start of the protests, on Sept 18, the army moved in. Thousands of students and activists were killed. Ohn Gyaw, the foreign minister at the time, in an interview in Yangon a few years after the event, insisted that only four people died - and they were killed in the stampede not by soldiers' guns. Most analysts suggest some 3,000 people died in the military's mopping up operations, while many military officials admit - albeit privately - that at least 6,000 perished. One intelligence officer close to the former intelligence chief, Gen Khin Nyunt, who is now under house arrest, told The National recently that Khin Nyunt's own assessment was that more than 10,000 people were killed. "Many bodies where quietly cremated so that there was no evidence of the massacre," he said.

Since then, there seems to have been very little movement towards genuine political change with many fearing that the country is destined to remain under a military dictatorship for decades to come. "What is certain is that change will only come from within the country," said Aung Zaw, the editor of the independent Myanmar news website and magazine Irrawaddy. "But more than that, I cannot predict."

Hopes of a new era were raised this time last year, when scores of monks joined street protests against the military regime and spawned a new movement called the Saffron Revolution. Again the military's only course of action was to respond with brute force, sending in the army and jailing protesters. Although residents are desperate for change, no one wants a repeat of the massive upheaval that happened in the wake of 1988. Yet at the same time, they were on the cusp of change.

"We were on the brink of giving in to the protesters," Brig Gen Thein Swe, a former senior intelligence official now serving 197 years in prison for corruption and treason, told a close confidante. "If the demonstrations had gone on for another two weeks, we would have been forced to give up and withdraw back to the barracks." But faced with such a wave of bloodshed, the protesters gave up first, and many fled abroad.

More than 250,000 Myanmar citizens have sought political refuge since 1988. The first batch took months to trudge through the jungles along Myanmar's border areas with China, India and Thailand. They hid from troops who would have killed them on sight, and suffered illness and disease - many were killed by diarrhoea, malaria, dengue fever and malnutrition. Thousands have poignant personal stories of tragedy. All left parents and siblings who they have not seen for more than 20 years. Others left their children in the care of grandparents.

Although the Saffron Revolution cannot be compared too closely to the events of 20 years ago, it did politicise a new generation of students - all of whom are too young to remember 1988. They are unlikely to return to the streets as the root causes of last year's protests - spiralling food and fuel prices - have now been resolved. But one lesson of the past 20 years is that protests do not always produce political change.

"You can expect spontaneous demonstrations against the military - but the problem is that you have to be organised," said Min Zin, a leading political activist who fled Myanmar more than a decade ago and is currently studying in the United States. "My concern is whether it can lead to a genuine political change." The junta now has forced the country to ratify a new constitution, which essentially institutionalises military rule, and promised fresh elections within the next two years. Myanmar's military rulers face a quandary, for they now have to seek the public's support as they try to move from military to civilian government as outlined in the new constitution.

The next two years will be uncertain as the regime prepares for these polls. "It is in times of uncertainty that protest and change seems to happen in Myanmar," said Win Min, a Myanmar academic at Chiang Mai University in northern Thailand. "The next two years are likely to be volatile - with more protests, led by the monks and the students, are almost certain." @Email:ljagan@thenational.ae