NEW DELHI // It is rough being an employee of Torrent Power Limited in Agra. Furious residents regularly take staff of the power distributor hostage or beat them up, stone-throwing mobs besiege the firm's high-walled compound, and one official recently was hospitalised after he was hit on the head with a brick.

On some days there are more than 10 protests staged around the city against Torrent, which won the franchise to supply power to Agra in 2009. When it took over, rampant theft and a failure by the authorities to crack down on defaulters meant that 70 per cent of electricity consumed in the city was not paid for.

Torrent's efforts to make customers pay have triggered a citywide backlash and aflood of complaints that it overcharges, uses heavy-handed tactics against defaulters and deliberately limits the number of hours of electricity each day to save money.

"Torrent is cheating people and that has made them angry," said Ram Shankar, the member of parliament for Agra, who said he receives up to 15 complaints a day from constituents unhappy about the penalties. "If they don't attend to people, they will be beaten up."

The company's defence - that it inherited a ramshackle network that had suffered from years of underinvestment and that the blackouts are beyond its control - has fallen on deaf ears.

Torrent's woes in Agra, home to the country's most famous monument, the Taj Mahal, illustrate how India's efforts to modernise its economy are often thwarted by local politics that feed on fear of change.

It is also a cautionary tale for the government, which has unveiled a bailout plan for debt-ridden electricity distribution companies - most of which are owned by states - and made it a condition for them to look at adopting the distribution franchise model to help cut massive losses.

Torrent's experience highlights the perils for companies hoping to benefit from the privatisation drive, together with the challenges facing India as it grapples with chronic energy shortages that stand in the way of its ambitions to become a global economic power.

The electricity distribution companies are at the heart of the power crisis and were blamed for one of the world's worst blackouts in late July, when three of India's five transmission grids collapsed, cutting electricity to states where 670 million people live - more than half of the country's population.

The companies have racked up losses of more than US$46 billion (Dh168bn) because of unrestrained power theft, leakage from a poorly maintained network and the reluctance of state government to raise tariffs to meet higher generation costs. Politicians fear a revolt by voters, many of whom view free electricity as a right.

Privatisation, in particular the franchise model, is seen by many as key to solving the crisis. But as Torrent's experience in Agra shows, it is hugely risky and a hard way to make money.

To succeed means upending a deep-rooted culture of non-payment and gaining the support of populist-leaning state governments.

Private power companies that dare to venture in face a complex web of political patronage and deep-rooted corruption, involving shady middlemen who organise illegal hookups to power-lines, pay government officials to settle bills for smaller amounts and, for a fee, will keep creaky transformers running.

"To bring about privatisation requires enormous political will," said Murli Ranganathan, the director of Torrent. "Without political will, without administrative support, you will not be able to convert this model into success."

On the face of it, the media-shy Torrent Power seems to be acutely aware of the political environment in which it operates.

It was the biggest single corporate donor to the ruling Congress party and the main opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) between 2003 and 2011. It is perceived by opposition politicians there as being close to Chief minister Narendra Modi, who is viewed as a strong contender to become the next prime minister.

Politicians are perceived to be riding the wave of popular discontent, which stems not just from the new reality of being forced to pay for electricity, but also from the steep penalties charged for theft.

Mr Shankar, boasted of organising violent protests outside Torrent's offices.

"We camp at their office. Most employees run away. Those who are left behind get beaten up," he said.

Torrent officials said some workers who raided homes to disconnect consumers for non-payment had been taken hostage by residents, usually for several hours at a time. Others had been detained to highlight complaints about delays in dealing with power cuts. Yet more employees had been beaten or punched.

Agra, however, is only one side of the story of India's experimentation with the distribution franchise model. The other half of the tale involves the same company but a different city, Bhiwandi, on the outskirts of Mumbai. Given Torrent's travails in Agra, it is one rich in irony.

The franchise model now being championed by reform-minded policymakers in India won acceptance because of Torrent's success in dramatically cutting distribution losses in Bhiwandi, a grimy textile town of less than a million people.

When Torrent took over in 2007, Bhiwandi paid for barely 40 per cent of the electricity it consumed. Three-quarters of consumers were not accurately metered and transformers failed frequently.

Within just four years, 99 per cent of consumers were metered and losses were cut by more than 80 per cent. Torrent's success lay in extensive security of the network and vigilance that curtailed theft. Investment in infrastructure ensured quality of supply.

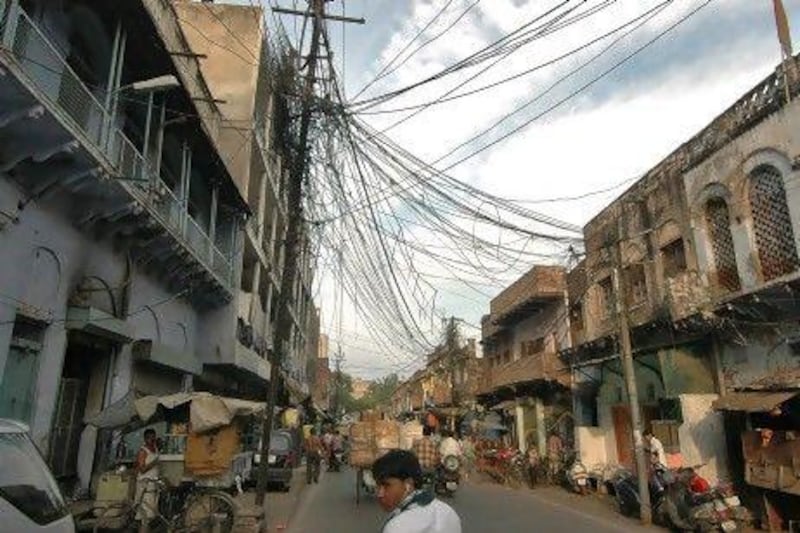

Bhiwandi does not provide a picturesque backdrop for one of India's biggest privatisation success stories. Its rutted roads and rotting buildings blackened by pollution belie the fact that it is one of the country's main textile hubs.

About 600,000 power looms are packed into factories that are sometimes little bigger than garages, and tended to by sweating men stripped to their waists.

When Torrent arrived, it faced a wall of opposition from factory owners, politicians and residents who objected to meters being installed and having to pay bills in full for the first time.

In a foretaste of what was to come in Agra, mobs attacked the company's offices and staff were assaulted.

But that is where the similarity with Agra ended. Unlike Uttar Pradesh, the government of Maharashtra, the country's richest state, is much tougher on electricity theft.

Arrests were made and police deployed in large numbers to protect Torrent's offices. The political backing gave the company the space it needed to rebuild the electricity network. Once it was able to demonstrate results, with a better power supply, the opposition began to fade.

"In this state, the political leadership decided to give political support for every activity for the reduction of loss," said Ajoy Mehta, the managing director of the Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Company. "They have said very clearly, 'we are not here to protect dishonest and lawbreaking citizens'. That is the main reason [Bhiwandi] succeeded.

"The whole concept is correcting the psychology. Somewhere, historically, we've made our people believe that any service given by the government need not be paid for," he added.

* Reuters