MANILA // The Philippines is to wind down the near 30-year hunt for the embezzled wealth of Ferdinand Marcos, with billions of dirhams of the fortune still missing.

With the late dictator's widow and children back in positions of political power in the country, and the government tightening its belt, the cost of the pursuit has become prohibitive, said Andres Bautista, the head of the Presidential Commission on Good Government.

"It has become a law of diminishing returns at this point," he said at the commission's offices, a now rundown building where Marcos' oldest daughter, Imee, once held office.

"It's been 26 years and people you are after are back in power," he added. "At some point, you just have to say, 'We've done our best', and that's that. It is really difficult. In order now to be able to get these monies back, you need to spend a lot."

Mr Bautista, 48, left a high-paying corporate job two years ago to answer a call to help the government of President Benigno Aquino, who had promised to end corruption and uplift the lives of millions of poor Filipinos.

He and like-minded young lawyers who joined the agency soon discovered that reforming the underfunded commission - itself prone to corruption - while at the same time going after powerful people was no easy task.

Despite numerous criminal and civil cases being filed against them, none of the Marcos heirs or their cronies, who have been accused of plundering government coffers, have been successfully prosecuted. High-powered lawyers have been used to tie up the judicial process for years on end.

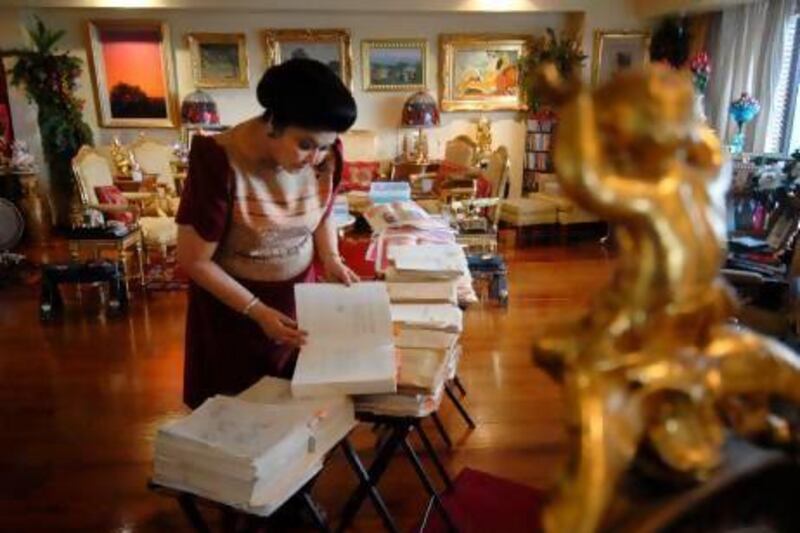

Long-term chronic mishandling of the commission led to an unmanageable paper trail and evidence went missing, leading to bitter losses in litigation, Mr Bautista said.

"These accusations [against commission officials] are not without basis," he said. "They were the ones in charge of guarding the chicken coop and some of them helped themselves to the eggs."

The president's late mother, and democracy icon, Corazon Aquino, replaced Marcos after a bloodless revolt ended his 20-year regime in 1986, and she sent him and his family into exile in the United States.

She made her first priority the creation of the commission, which was tasked with recovering all of the Marcos fortune. Conservative estimates put the value of assets and funds looted from government coffers at US$10 billion (Dh36.7bn).

But before she left office in 1992, Aquino allowed Marcos's flamboyant widow, Imelda, notorious around the world for the thousands of pairs of shoes she owned, to return home, along with her son and two daughters.

And over the past two decades the Marcos family has regained and consolidated its political base.

Marcos's son and namesake, Ferdinand Marcos Junior, is a senator who has hinted at contesting the presidency in 2016.

Imelda is expected to run for a second term in the House of Representatives in May 2013, while Imee, the governor of the family's Ilocos Norte provincial bailiwick, is also widely thought to want a second term.

"There is still a lot of mystery surrounding the fabled wealth, and my sense is there is still much more out there," said Mr Bautista. "Our problem now is that everyone is back in power. That does not in any way make our job any simpler."

Since its creation, the agency has recovered 164bn pesos (Dh14.69bn), some of it invested in high-end New York property, jewellery, and about $600 million stashed in secret numbered Swiss bank accounts.

The jewellery, including a 150-carat Burmese ruby and diamond tiara, is locked in a vault at the central bank. The international auction house Christie's has estimated it could sell for up to $8.5m.

More recently Mr Bautista worked closely with the New York district attorney's office to charge a former personal secretary of Imelda Marcos and two others over a conspiracy to sell a Monet painting that had been bought by the family.

Marcos, an astute art buyer, distributed his priceless collection of at least 300 artworks to cronies when his regime was about to crumble. Only half have been recovered and the rest are missing, said Mr Bautista.

He said he had recommended to Mr Aquino that the commission wind down its operations and transfer its work to the justice department.

If the president agrees, he would have to get parliament to pass a law abolishing the agency.

The Marcos family "have the resources to go head-to-head with us in respect to litigation", said Mr Bautista. "Why do you think forfeiture cases are still languishing 26 years after?"

The agency's annual budget of less than 100m pesos was only enough to pay its staff of about 200, many of them young lawyers who turned down high-paying jobs elsewhere, he added.

"It's a lonely job. It doesn't win you any friends."