MANILA // Should journalists working in high risk areas be allowed to carry guns to protect themselves? It is a question many journalists in the Philippines have been asking for years and one being asked more frequently since the massacre late last year of 57 people, including 31 journalists, in the worst case of political violence ever seen in the country. Not only did the killings put the Philippines in front of war-torn Iraq as the most dangerous country in the world for working journalists, it was also the biggest number of journalists ever killed in one day while on the same assignment.

Among journalists living in the relative safety of Metro Manila, few feel the need to carry a gun, but for the hundreds of men and women of the Fourth Estate in other areas, especially in the restive south of the country, it is fast becoming a question of survival. John Unson, chairman of the Cotabato City chapter of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines, said recently the "advocacy for arming reporters in the south has intensified" since the November 23 killings in Maguindanao, a poor province on the southern island of Mindanao.

"While many journalists outside of the hostile southern provinces are opposed to journalists keeping guns for their protection, most media practitioners in the region have no alternative but to arm themselves," Unson said. "Mindanao is not the easiest place to work as a journalist," said one reporter who works in Muslim Mindanao and did not want to be named. "You work in constant fear that whatever you write or say may offend somebody locally. Down here, no one bothers with filing libel or defamation actions in the courts like they do in other countries. A bullet costs around 20 cents [70 fils] and you can hire a hit man for a hundred bucks. Killing a journalist is much cheaper than going through a long and costly court case," he said.

"Yes, I carry a gun. I have had too many threats made against me and my family. It's not a question of ethics, it's a question of protection - for me and my family. Does it make me a bad journalist? I don't know, but when I go out into the province on a story I feel a hell of a lot safer knowing I am armed." Dennis Jay Santos, a journalist based in Davao City for the Philippine Daily Inquirer, said: "I do not personally subscribe to the idea of arming journalists.

"Even working in a climate of constant conflict and impunity, I still adhere to the old traditions and values of journalism, which is to always stay neutral in order to achieve objectivity," he said. "I absolutely agree with the self-defence concept as a basic human right, but a journalist should also know that the working environment can always be hostile and unforeseen events may occur." With elections due in May, the country has been placed under a total gun ban, but some journalists working in high-risk parts of the country are looking for an exemption. According to the Commission on Elections, which overseas the elections, no formal requests have been made to exempt some journalists from being armed during the election.

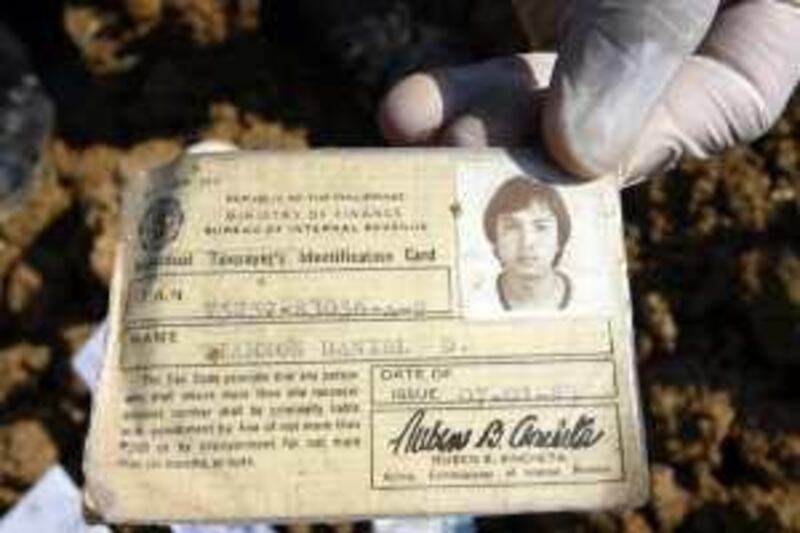

Another journalist from Cotabato City, who did not want to be named, said despite the ban he still carries a gun. "At least at night - you would be crazy not to in this town," he said. "During the day the gun stays at home. I would, however, like to see some exemptions for journalists working in the high-risk areas." Even before the November massacre, journalists in the provinces were being murdered on a regular basis by hired gunmen. According to the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), 136 journalists were killed in the Philippines since democracy was restored following the non-violent overthrow of the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in February 1986.

Since Gloria Macapagal Arroyo came to power in 2001, 68 journalists - apart from those killed on November 23 - have been murdered in the Philippines and only four people successfully prosecuted in two cases, according to IFJ. The journalists' union "does not advocate journalist carrying guns. It doesn't help the cause of personal safety or press freedom," Nonoy Espina, its vice chairman, said. "But here in the Philippines many journalists, especially those down south [in Mindanao], do have an ethical dilemma over the issue."

The IFJ, in a report on Maguindanao killings, Massacre in the Philippines, said: "The massacre underlines the terrible dangers that Filipino journalists face. It also highlights the inability and unwillingness of the State to ensure the protection and safety of journalists who are seeking to perform their duties to keep the public informed. "The massacre could not have taken place without the existing culture of impunity in the Philippines, particularly regarding extrajudicial killings and attacks on media," it added.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae