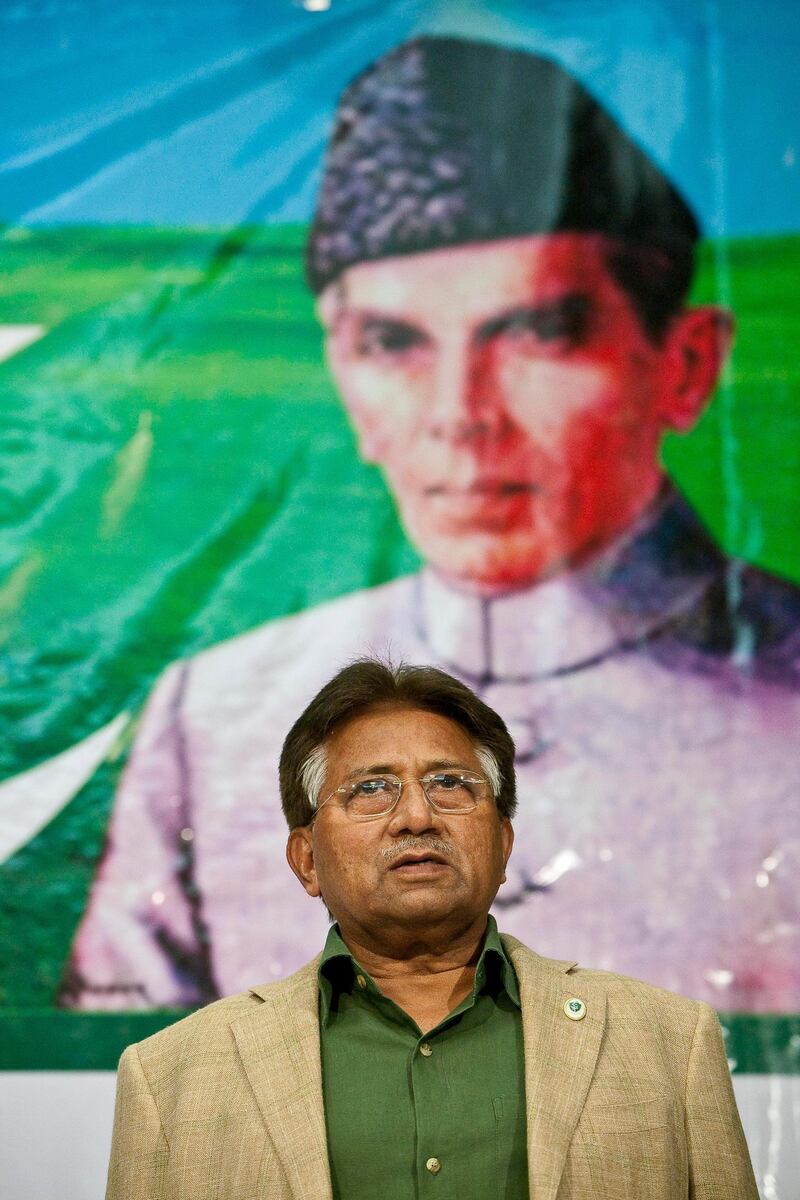

In a country where the military is considered the most powerful institution and largely immune from prosecution, the conviction of former army chief Pervez Musharraf for treason is remarkable.

Pakistan's military has ruled the country directly for half of its life through coups, and has been accused of meddling in politics by promoting its own favourites for much of the rest.

While the generals deny political scheming and say they acknowledge civilian rule, opposition politicians and rights groups warn that behind the scenes the military has a growing grip on power.

In such a climate, for a former chief of the army staff to be sentenced to death for suspending the constitution is an unprecedented challenge.

That the military considered it provocative was evident in its response after the verdict. It left no doubt that the generals were angry and a clash with the judiciary is now likely.

“The decision given by the special court about Gen Pervez Musharraf has been received with a lot of pain and anguish by the rank and file of Pakistan armed forces,” the military's information wing said.

The armed forces accused the court of ignoring legal due process and denying Musharraf his right to defend himself.

Pakistan's forces “expect that justice will be dispensed in line with the constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan", they warned.

With Imran Khan's Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf government considered to be closely aligned to the military, his ministers may also come out against the verdict.

The court's ruling is the second time in less than a month that judges have issued a rebuff to the military.

Late last month, the Supreme Court briefly blocked a three-year extension for the chief of army staff, Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa, before passing the decision to Parliament to rule on.

Musharraf has the right to an appeal against his conviction and if he loses that, there is still the possibility of a presidential pardon.

Farzana Shaikh, an associate fellow at the Chatham House think tank in London, said she was sceptical the sentence could ever be implemented. Musharraf is in Dubai in self-imposed exile.

“Obviously this decision is unprecedented and in that way clearly historical," Ms Shaikh said. "But I think it's also important to bear in mind that it's very likely to remain a symbolic decision.”

A bigger question is whether it will deter military power plays in the future, she said.

It could be significant that the ruling had found him guilty of suspending the constitution in 2007, not of originally overthrowing the civilian government in 1999.

“That still leaves people thinking that if things don't go the military's way, it would still be free to mount a coup,” Ms Shaikh said.

No one has heard yet from the man at the centre of the drama, Musharraf. But 11 years after he left power, his legacy continues to divide the country.