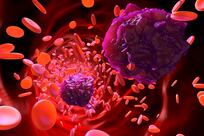

LAHORE // Pakistan's medical scientists have warned the government of an emerging liver disease pandemic, after a first nationwide survey revealed that some 12.5 million people are infected with the hepatitis B and C viruses. The still-confidential results of the survey, conducted by the Pakistan Medical Research Council, conclude that 4.9 per cent of the country's estimated 170m people are carriers of the deadly hepatitis C virus. The survey findings are based on the screening results of 50,000 blood samples from every district in the country. An additional 2.5 per cent of the population has contracted hepatitis B, considered less of a threat because it can be prevented by vaccination, and develops into chronic disease in only one in 10 cases. The alarming data confirm the results of earlier case studies conducted at 220 front line hospitals, which had estimated hepatitis C infection at five per cent to six per cent and hepatitis B at three per cent to four per cent. As such, it comes as no surprise to leading liver physicians. "Over the last 20 years, acute virulent hepatitis has surpassed both heart disease and strokes as the most common cause of hospital admission and fatality," said Dr Aftab Mohsin, a professor of medicine at Services Hospital in Lahore. "I doubt there is a more infected country in the world," he said. His words are borne out by a round of the 40-bed ward under his charge. Occupying 10 beds were patients displaying dramatic cirrhotic symptoms, predominantly the distended bellies commonly associated with famine victims. Medical science has yet to develop a vaccine for hepatitis C, which was not discovered until 1979 because of its stealthy nature. Carriers of the virus take between 10 and 25 years to develop full-blown symptoms, meaning that six out of 10 Pakistani patients are not diagnosed until they need a liver transplant - a life-saving procedure unavailable in Pakistan. By that time, they have passed on the infection to one in two family members. "We are seeing now what happened 20 years ago," said Dr Anwaar Ahmed Khan, the dean of Lahore's Sheikh Zayed Postgraduate Medical Institute. "Ninety per cent of carriers don't even know they are sick." Most Pakistanis are oblivious to the hepatitis prevalence or how easily it is contracted, usually through the skin and mouth from blood-tainted sharp instruments wielded by barbers and careless or unlicensed doctors, or from unscreened blood and illegally resold used syringes. Public ignorance is largely because of government reluctance to sound alarm bells until the recommended medication, interferon, was a proven success. That was deemed a scientific necessity by doctors at the helm of the national hepatitis programme, launched in Jan 2006, because of the known existence of 11 different genotypes and 150-plus subtypes of the fast evolving hepatitis C virus. Health ministry officials in Islamabad said they also needed time to persuade physicians across the country to prescribe the six-month course of unfamiliar interferon medication, partly because of its very unpleasant side effects. One hospital in the North West Frontier Province capital of Peshawar went as far as to return unopened the first shipment of free medication, worth about US$1,000 (Dh3,670) per course on the open market. Some 34,679 tests later, it has been established that more than 80 per cent of Pakistani carriers harbour genotypes 2 and 3AB, which are among the easiest to treat. "Some types are unidentifiable, but the response to treatment has been excellent - thank God," said Dr Sharif Ahmed Khan, the national hepatitis programme manager. As positive responses to treatment became known in 2006, demand for interferon burgeoned, and 22,279 of the poorest patients were successfully treated for hepatitis C in two years, before Pakistan's long political transition put funding on hold in late 2007. That may now be forthcoming. Prompted by frequent hepatitis-related questions in parliament, Yousuf Reza Gilani, the prime minister, is known to be taking a keen personal interest, according to doctors who have briefed him behind the scenes over the past month. Plans for the country's first dedicated liver hospital are being added to federal government development plans, while Mr Gilani has let health ministry officials know he would like his title affixed to the nomenclature of the national hepatitis programme ahead of a planned mass media awareness campaign. At Services Hospital, patients who cannot afford medication are baffled by their sickness. Typically, they were diagnosed only after suffering flu-like symptoms and fatigue for three years before turning up at a hospital. Even as they edge towards death, their thoughts turn to their poverty. "We haven't had any income for nine days," said Kishwar Naheed, a terminally ill mother of three whose husband, a daily wage labourer, must attend to her as there is only a single nurse for the whole ward. For some attendants, concerns are of a more morbid nature. One woman cornered Dr Mohsin as he toured the ward, berating and pleading with him. "I prescribed medication yesterday, but it is unavailable in the hospital," he said. "She is begging for medicine for her dying husband." * The National

Pakistan faces liver disease pandemic

Medical scientists have warned the government, after a first nationwide survey revealed that some 12.5 million people are infected with the hepatitis B and C viruses.

Editor's picks

More from the national