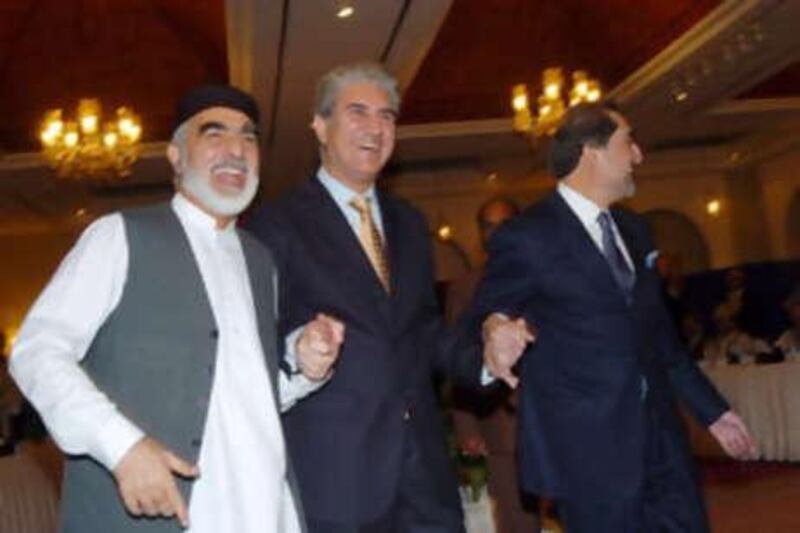

ISLAMABAD // Afghan and Pakistani political leaders gathered in Islamabad yesterday to find a way to encourage talks with the Taliban on both sides of the border, as the insurgency has created a crisis in both countries. The closed-door "mini-jirga" will over two days push not only for the opening of dialogue with militants, but some delegates will also advocate the withdrawal of western forces from Afghanistan as the only way to quell the Taliban onslaught. The big questions are who do they talk to and on what terms? No one can be in any doubt of the urgency of the situation, as 2008 has become easily the bloodiest year in the two countries since the Taliban regime in Afghanistan was toppled in 2001. Islamists have large parts of the Afghan countryside under their control, while nuclear-armed Pakistan has been destabilised by a well-organised campaign of violence. "People understand that a bullet is no solution. This will be solved by talks," said Malik Waris Khan Afridi, a Pakistani delegate, on the sidelines of the meeting. "But we also have to ask Nato and the US what their aims are." In Afghanistan, anti-government forces are established in 13 Pashtun provinces, led by Helmand, Nangarhar, Paktia and Ghazni. According to a tally kept by John McCreary, a former Pentagon analyst, in his NightWatch report, there were 1,880 attacks by the Taliban through the end of September, compared to 1,702 in the whole of 2007. In Pakistan, a copy of the Afghan Islamic movement has taken over the 25,900 sq km tribal border area with Afghanistan, and reached deep in the adjoining North West Frontier Province. As well as seizing swathes of territory, the Pakistani Taliban, and their allies from other militant groups, have staged a savage suicide bombing blitz. Al Qa'eda has melded with home-grown extremists in both countries, ideologically and logistically, giving Osama bin Laden's terrorist group an army of thousands. Pakistani Taliban fight in Afghanistan, Afghan Taliban find sanctuary in Pakistan, the main factions in both Talibans accept the ultimate leadership of al Qa'eda, which is headquartered in Pakistan. That makes the war in the two countries inextricably linked. The mini-jirga in Islamabad, a two-day meeting of 50 politicians, clergy and tribal chiefs from the two countries, with the backing of their governments, is charged with opening talks with "the opposition". It is a much-delayed follow-up to the grand jirga held in Kabul more than a year ago (the Afghan side was at pains to blame the Pakistanis for the delay). Yet Islamabad and Kabul appear to rule out talks with the hardcore Taliban, leaving the initiative in a muddle. Abdullah Abdullah, the leader of the Afghan side and a former foreign minister, told the gathering that they should negotiate with "those who accept the constitution of Afghanistan and accept the principles of non-violence" in his opening speech, which was open to the press. Farooq Wardak, the deputy head of the Afghan delegation said that "we are not prepared to talk to the enemies of humanity". But some participants said the official line was unrealistic and would not lead anywhere. Rustam Shah Mohmand, a Pakistani delegate and a former ambassador to Afghanistan, said: "Unless the governments are prepared to do a midcourse correction and take risks, nothing will change. "You need to talk to the people who have taken up arms and are battling you, you just can't be an escapist and say only those willing to lay down their arms," Mr Mohmand said. "In the Afghanistan and tribal areas context, it is ridiculous. People don't lay down their arms in this culture." So, it is off limits for the mini-jirga to talk to the representatives of Mullah Mohammed Omar, founder of the Afghan Taliban, Jalaluddin Haqqani, the veteran Afghan jihadist, or Baitullah Mehsud, head of the Pakistani Taliban. It is hard to see who the mini-jirga, known as a jirgagai, envisages speaking with. One delegate from Afghanistan, Bakhtar Aminzay, a senator, said it could be a two-stage process, with dialogue beginning with those who accept the writ of the government, followed by the real insurgents. "We will be going slowly, very slowly towards that," Mr Aminzay said. Aside from the mini-jirga, there are other, secret channels of communication undoubtedly taking place, in both Pakistan and Afghanistan, with the militants that the two governments refuse to officially speak to. One instance of this was a get-to-know-you meeting in Saudi Arabia last month, news of which was leaked, then confirmed this week, between figures associated with the Afghan Taliban and the Kabul government. Nawaz Sharif, a former Pakistani prime minister, was also there. There has been a very notable lack of success in winning Taliban elements over to the government side in Afghanistan. And, given their continuing success on the battlefield, it is hard to see that changing. At best, they would use dialogue, and any military pause that accompanied it, as a way of rearming and regrouping. The Taliban have already said they do not accept the Afghan constitution and rights accorded under it, especially to women. The other element of radical change - the departure of foreign forces - also seems to be off the table for now. There are clear signs the European members of the coalition are desperately seeking a way out of Afghanistan but that would be difficult while the US resolve holds firm. "It looks like Nato just wants to find a quick solution so they can declare victory and leave Afghanistan," said Haroun Mir, deputy director of the Afghan Centre for Research and Policy Studies, a think tank in Kabul. The Pakistani and Afghan governments think "if they engage with the Taliban, they can isolate al Qa'eda. This is a big mistake," Mr Mir said. "The new generation of Taliban makes no distinction between themselves and al Qa'eda." sshah@thenational.ae

Pakistan and Afghanistan hold 'mini-jirga'

Afghan and Pakistani political leaders gathered in Islamabad to find a way to encourage talks with the Taliban.

Editor's picks

More from the national