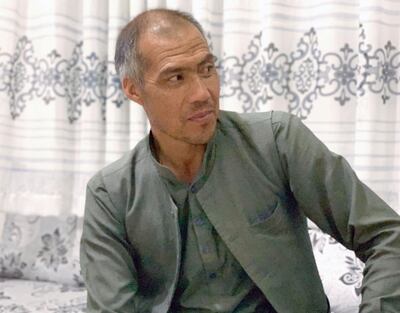

As the sun set, we hurried through the streets of Dasht-e-Barchi on the western edge of Kabul. Our host, 40-year old Baqir Sangari, had called several times to check the instructions to his house in the largely Hazara Shiite community.

Arriving a few minutes after iftar, we were welcomed by Baqir and invited to sit for the wide and colourful spread of food. Baqir’s wife, Momina Sangari, four daughters and two sons sat waiting to start despite not having eaten since the sun rose many hours ago.

“There is a saying, the more people join you for iftar, the better the food will taste,” Baqir said, as Momina and two of his daughters begin serving generous portions of homemade bolani, a fried bread stuffed with potato and leek.

Baqir, from the Maidan-Wardak province of central Afghanistan, works as a taxi driver in Kabul. The family gets by on Baqir’s income of about AFN 14,000 (Dh 650) to 15,000 (Dh 695) a month – average for a driver but well under the amount needed to comfortably support a family of eight in Kabul.

As the family began to eat, the conversation moved between the girls’ education – they had to leave their afterschool English language classes because it was too expensive – and the deteriorating security situation of the country. “Each Ramadan becomes more difficult than the one before. There is more tension every time,” Baqir said.

“We try not to talk about such negative things around the children, but between ourselves, we often discuss how bad things keep getting,” 35-year-old Momina said. “Those conversations end with a prayer for a better future, because what option do we have otherwise?” she said, wearily.

For the Sangari family, the 18-year Afghan conflict comes with an additional challenge of being from a marginalized sect – the Hazara community has historically been persecuted for their Shiite faith.

While things improved after the fall of the hardline Sunni Taliban regime with the United States-led invasion in 2001, there is a new threat posed by a brutal and growing ISIS insurgency. The extremist group has been gaining ground and has targeted the minority several times in the last three years, conducting attacks on Shiite places of worship, political and civil gathering and even schools in the Hazara dominant areas.

UN figures for last year reported 747 civilian casualties after 19 incidents of sectarian-motivated violence against Shiite Muslims in Afghanistan – a 34 per cent rise in the toll from previous years.

Several of these attacks in Kabul took place in the neighbourhood where the Sangari family live, killing close relatives. In March, Baqir’s nephew was helping search people entering a gathering to honour the Hazara Shiia leader Mazari. He was patting-down a suicide bomber when the man detonated his device. Baqir’s nephew was the first of at least 11 people killed.

“We do feel very unsafe. It feels like we are in the middle of a war,” said Momina, who has lived her entire life in Dasht-e-Barchi but says it has never felt this dangerous.

"When our kids are at school or private classes, I worry if they will return safe. There have been constant threats from Daesh [ISIS] against schools that educate girls," she said. "One learning centre close by has already been targeted." In August 2018, a private school in the area was hit by a suicide bomber, killing nearly 50 children and injuring scores of others.

In the wake of the attack, many families – including the Sangaris – kept their children at home.

“I didn’t let the kids go school for a month but then I thought to myself, ‘when will this end?’ I can’t stop their education because of this fear. We want them to grow, so we started their school again and now I always ask God for their safety,” she said.

Baqir says he believes that ISIS is targeting the community not only because of their religion but because a number of Afghan refugees joined Iranian militias to fight in Syria. “But our people are not in a position to fight back against them on our own,” he added, asking for help from the government and international community to end the violence.

“We are part of this society, we work, we pay taxes and all we want from the government is security.”

While the targeted mass violence is relatively new, the Sangaris have faced discrimination all their lives. Baqir and Momina were married during the Taliban era in the late 1990s and started a family while navigating life as a young couple under the restrictive rule of the group.

“We are easily identifiable as Hazaras because of our distinct features and our dialect is also different, so they would recognize us and treat us badly,” said Baqir.

He is concerned about the prospect of seeing the Taliban reenter the government if the ongoing peace talks between the US administration and the insurgent group leads to a power-sharing agreement.

“The mentality of the Taliban is different than ours. They will always think we are Hazara and they will harbour negative thoughts about us. I don’t think it will be such a good thing,” he said.

For Momina, the return of the Taliban also brings back painful memories.

Over several cups of chai, at the end of the meal, she retold stories of her life under the Taliban. “I was in seventh grade when the Taliban took over Kabul. I had so many dreams, I wanted to be a teacher or a doctor even, but one day they came to Kabul and shut down all our schools. I was engaged a few months after, and that was the end of my ambitions,” she said.

“We couldn’t allow women to leave the house and if you did, you had to be under a long burqa and even cover your ankles with socks. I was afraid so I stayed indoors most of those years, but I saw many women who were beaten in public for as little as not wearing socks,” she said.

As well as being from a marginalized group, being parents to four girls adds to the Sangaris’ worry about a return of the Taliban.

“I push my daughters to study and do better, even though we are not doing financially well. I don’t want them to end up like me,” Momina said, looking with pride towards her children.

When asked, what they would choose if they had to pick between peace and their freedom, the Sangari women responded in one voice, “We want both.”

Despite worries, Momina hopes that all Afghans will come together and protect the rights they have won since the end of Taliban rule if the group is given a role in government.

“We all need to be united if we have to protect our future,” she said.