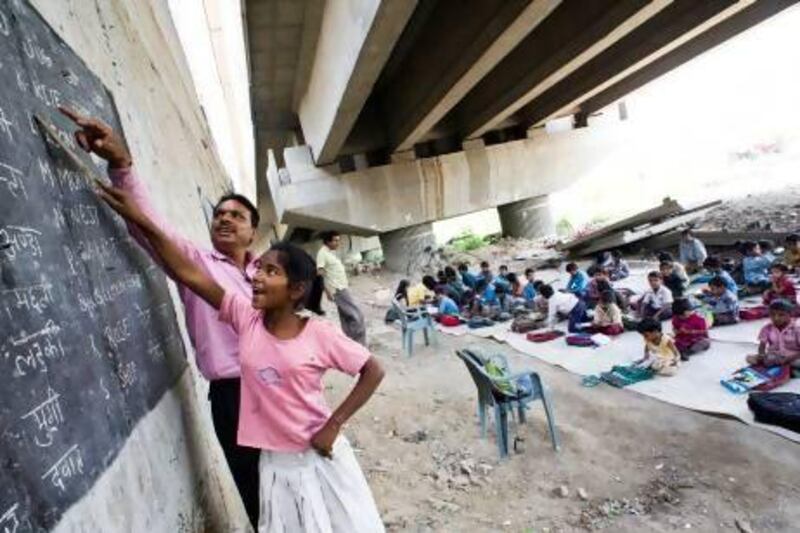

NEW DELHI // Rajesh Sharma's school has no desks or chairs. The "roof" is a metro railway bridge 10 metres overhead. The blackboards are black rectangles painted on the wall of the adjacent station. Despite its makeshift nature, the school offers hope to poor children in the neighbourhood.

Mr Sharma, 41, who runs a grocery across the street from the Yamuna Vihar metro station, started the school three years ago to offer free education to the children of the local labourers and farmers.

Being poor and mostly illiterate, the families of these children usually either see no need for them to be educated, or worry about the costs involved, particularly when sending them to school means they cannot help to support the family.

Veeresh Kumar, 9, has been attending the classes for a year since his family moved to Delhi from Uttar Pradesh in search of work. His father is a farm labourer in the nearby fields that line the banks of the Yamuna river.

"I want to become an engineer someday because I like numbers and I like how English sounds when I speak the words," Veeresh said.

He attends a government school, which is unusual among his peers whose families squat along the river. But the quality of teaching in government schools is uneven and absenteeism by teachers plagues the system. So Veeresh must endure a schedule that would be exhausting even for most adults.

His day begins at 9am with classes at Mr Sharma's school. At 11, he walks home for a quick lunch of rice, a piece of bread and a watery potato gravy. He then changes into his uniform of light-blue shirt and dark-blue trousers, washes his face and sets off for the government school a kilometre-and-a-half away. He returns home at 5pm and does his homework.

Veeresh's family is supportive of him going to school, despite not quite understanding his excitement about it.

"We can't read or write so we have no idea how he is doing in school. He will show us his work sometimes and say, 'Look! I got all the answers right', but I cannot understand a thing," said Chameli, Veeresh's grandmother, who shares a two-room hut made of mud, straw and plastic sheeting with two sons, their wives and three grandchildren.

Mr Sharma understands the yearning to learn but not being able to fulfil the desire. He dropped out of college in his third year because of his family's financial difficulties. The idea to open a school came to him on a morning walk along the river when he saw some children weeding and picking flowers.

"I asked them which school they go to and they looked at me at with no answer," Mr Sharma said.

"It had not occurred to me before that not every child has access to a school."

So Mr Sharma and his friend, Laxmi Chandra, a retired teacher, teach classes under the metro bridge for two hours every weekday morning. The students, who now number more than 70, sit on foam mats and recite after their teachers as trains rumble overhead and traffic rolls past a few metres away. While the younger children learn the English alphabet, those between 10 and 16 study mathematics, from multiplication tables to geometry, taught by Mr Chandra.

"These are not children who can afford private tuition to help them with their homework from school," Mr Chandra said. "We teach them in a way no one cares to."

Mr Sharma initially bore the entire cost of providing the children with textbooks, pencils and exercise books.

Over time, people who heard about the school began dropping off supplies, sometimes anonymously.

"One man came with 60 school bags once," he said. "He would not tell me his name or what he did. He said none of that mattered as long as the children got a decent education."

Mr Sharma started the school with the aim of providing children from poor families with a basic education.

However, after the government enforced the 2009 Right to Education Act last year, which guarantees free schooling for children between the ages of 6 and 14, Mr Sharma decided to focus on preparing the children for admission to school and helping them to cope with the curriculum.

But the children of farmers and labourers are reluctant to enrol, influenced mainly by the prejudice of their parents, most of whom are illiterate.

All it takes to enrol in government schools, which also provide free lunches, is for a parent to accompany the child to register them. Most parents of the children that Mr Sharma teaches are reluctant to do even that.

Being squatters, they have no residency papers and are loath to interact with the authorities, even in schools, for fear that it might draw attention to their illegally constructed homes.

Mr Sharma has to battle constantly to get parents to send their children to his classes for just a couple of hours each day.

"They say, 'My son is too old now to catch up with the rest of his age group and study. Let us put him to work'," he said.

"The excuses for the daughters are even worse. Most of the time they cannot even bring themselves to believe that she deserves an education. Other times they are just waiting to marry her off."

At 13, Kunti Kumari is one of the oldest girls studying the alphabet at Mr Sharma's school. She joined five months ago but stopped after a month. After a week, Mr Sharma went to see her parents. Kunti began to cry when she saw her teacher.

It turned out that Kunti worked alongside her parents in the fields. After the euphoria of her first month of learning wore off, she struggled to keep up with the burden of working and studying.

Kunti woke at 3am each day to cut roses from the family's bushes for her father to take to market by 6am. She then helped her younger sister, Babli, 11, with household chores before setting off to class. By the time she returned home and completed her share of work in the fields, she was often too tired to do homework.

"The parents, they just don't understand," Mr Sharma said. It was only after he made Kunti recite the alphabet from "A is for apple" all the way to "S is for ship" that her father was convinced that the two hours of daily schooling were worth it.

Kunti and her sister both attend Mr Sharma's school now, taking their two young brothers along instead of having to stay at home to babysit them while their parents are at work.

They no longer have to work in the evenings either, so they can do their homework.

But their father will still not enrol them in a government school.

"They don't understand the system," Kunti said. "I wish I could outright say I want to go to school, but I know I must help my parents support our family."