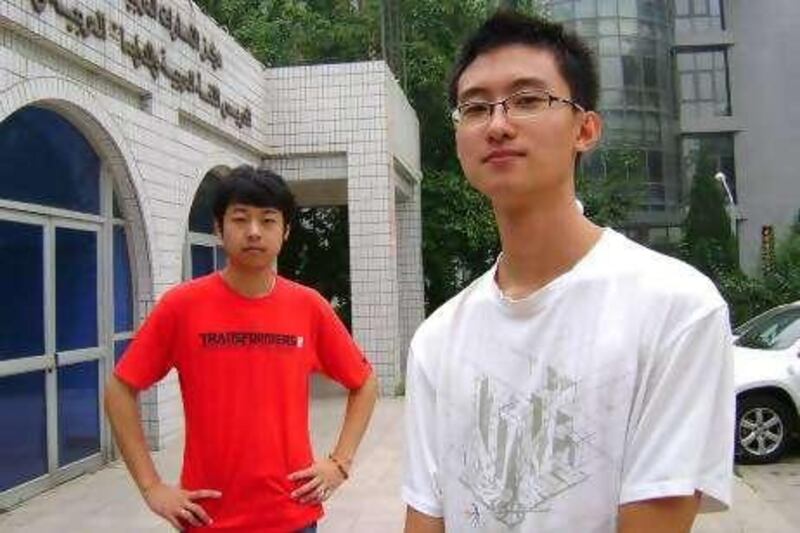

BEIJING // Hang Qichao believes he knows the way to a prosperous future: being able to speak Arabic. The 22-year-old student at Beijing Foreign Studies University cheerfully admits learning one of the world's most ancient and celebrated languages is not easy. In fact, he describes it as "very, very difficult".

But with trade links between China and the Arab world growing to the extent that people have talked of the creation of a "new silk road", Mr Hang thinks his hours spent trying to master the complexities of Arabic grammar and other linguistic intricacies will pay dividends. "There are several languages we could have chosen, but me and my classmates, we think [by studying Arabic] we have a better opportunity to find a job at the foreign ministry or another ministry or a company that has a business relationship with Arab countries," he said.

Mr Hang only has to compare where he is after three years studying Arabic with the progress of fellow students taking other languages to realise what a challenge he has set himself. One year studying a European language is enough, he said, for students to communicate fluently with locals. Yet even now he admitted he had not reached a similar level with Arabic. "Daily life we cannot say a lot of things," said Mr Hang, who added he could however discuss specialist subjects such as trade and diplomacy that his course emphasised.

Despite the difficulties, increasing numbers of young Chinese people are studying Arabic, and more universities in the world's most populous nation are teaching it. Ten years ago, just seven higher education institutions taught Arabic; today more than two dozen do. Moreover, some institutions that have long taught the subject have increased enrolment, with Beijing Foreign Studies University having seen student numbers go from 60 to more than 200.

Among the institutions that began teaching Arabic relatively recently is Xi'an International Studies University in Shaanxi province, which launched courses in the language five years ago and recruits up to 30 students to study it a year. Ma Fu De, the dean of the Arabic studies department, said there was a 100 per cent employment rate among students who had graduated so far. Some had gone into teaching, while others were working for major oil companies such as Sinopec and PetroChina with heavy ties to the Arab world. There was, he said, "strong demand" for interpreters.

"It's natural for this surge in interest among students who want to pursue a degree in Arabic studies," he said. But he added it was not just employment ambitions that made young people consider studying Arabic; it was also about a fascination with the Middle East and its traditions. "From our childhood we've read so many Arabic fairy tales like the 1001 Nights, so most Chinese students have a curiosity about this exotic Arabic culture," he said.

The very challenge of mastering Arabic is one of the attractions, according to Wei Xing, 21, a student at Peking University. "It's hard to learn so it's very interesting to learn," she said. "And there's a whole new world open to you when you are in command of this language." Ms Wei, who has been studying Arabic for two years, admitted she was "not very fluent" when she visited Tunisia last year, but achieved "daily communication" with the local people.

Trade statistics show how China and the Arab world are becoming closer. In 2003, bilateral trade was worth US$24.5 billion (Dh90bn), while five years later it was more than five times as much, at $132.9bn. The Middle East is a key oil supplier for China as its demand for petrochemicals grows in tandem with economic growth, while Arab countries have become important markets for Chinese exports. There are also growing cultural ties, with the Chinese government's Hanban organisation looking to set up more branches of the Confucius Institute in the Middle East. Zayed University is set to open one such branch in Abu Dhabi next year.

No wonder that people such as Sue Wenbo, 22, one of Mr Hang's classmates at Beijing Foreign Studies University, believes Arabic "for sure" is a better choice in terms of employment than Russian, which used to be a key foreign language in China in previous decades, or English. "China is trying to develop its relationship with Arab countries," he said. "Arabic offers more career opportunities." According to Ben Simpfendorfer, author of the book The New Silk Road: How a Rising Arab World is turning Away from the West and Rediscovering China and chief China economist for the Royal Bank of Scotland, around half the Chinese people studying Arabic are Muslims.

The increasing popularity of Arabic reflected wider growth in the learning of foreign languages in China, he said, as language skills were seen as the passport to a job with a foreign company or a posting overseas. "Languages get more attention from the Chinese government than they do in other countries," said Mr Simpfendorfer, who speaks both Arabic and Chinese. dbardsley@thenational.ae