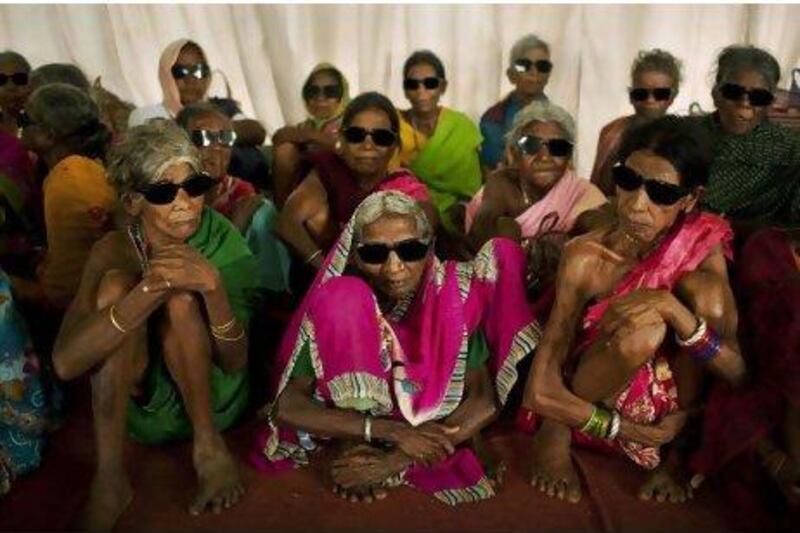

JAGDALPUR, India // Dozens of elderly villagers, tribal tattoos marking their scrawny arms, sit in a dimly lit hall. Hidden behind large sunglasses or with white bandages wrapped across one eye, they are all recovering from cataract surgery.

Most have never seen water gush from a faucet or pressed a switch to flood a room with light. Until their surgery a few weeks ago, they had never met a real doctor.

When a five-coach train with specialist doctors and operating rooms rolled into the town of Jagdalpur last month, it brought both hope and an acute reminder of all that is missing here.

The deprivation has turned this forested eastern area into a stronghold of the country's thriving Maoist insurgency. Advocates for the poor say the government's utter neglect of the region pushes its inhabitants into the arms of the militants.

The Lifeline Express, a charitable mobile hospital, is the closest the nearly 1.4 million people of this area will come to a functioning hospital.

For the past 20 years, the medical train has travelled to India's poorest and most backward areas to provide basic surgeries - from cataract procedures to correcting club feet and polio deformities.

Bastar district, where Jagdalpur is located, certainly meets all the criteria for the Lifeline Express' charity. It falls among the bottom five of India's 643 districts for development and health.

It is so uncharted and remote that gathering accurate data is as hard as getting social and health services to the district. But this much is known: it is the most backward area in the state of Chhattisgarh, where one in four children under the age of 4 suffers from acute undernutrition and more than half the adolescent girls are anaemic, according to Unicef.

The powder-blue train, decorated with pictures of rainbows and clouds, arrived at the Jagdalpur train station in July. In a little more than three weeks, the team operated on nearly 2,500 people for cataracts and on 20 others to fix twisted limbs so they could walk.

Dr Rajnish Gourh, supervisor for Impact India Foundation, the Mumbai-based charity that created the service, said those operated upon "would have lived and died with their problems but never managed to get help" without the medical train.

The train and its medical miracles allowed the elderly tribal woman Pacho to see again. The train also gave one-year-old Bhumika, born with a club foot, the promise of one day being able to run with her friends.

Bhumika's father Channu, looking anxious as he rocked the sobbing child to sleep in the clean and air-conditioned waiting area on the train ahead of her surgery, said: "There is only a nurse in our area and she doesn't even see us anymore. She said there was nothing she could do for us."

In the hundreds of small communities in Bastar's dense forests, villagers like Pacho and Channu live in a time warp with almost no comprehension of basic amenities that even the poor in most other parts of India can take for granted.

In these villages, all visible indicators of governance, such as electricity, drinking water, schools and hospitals vanish, and a new power centre emerges.

This territory is controlled by the Maoist rebels known as Naxals, for the eastern village of Naxalbari where the movement was founded in the late 1960s.

The rebels have tapped into a deep dissatisfaction among India's rural poor as a rapidly burgeoning economy brings very visible wealth to only parts of the country.

The rebels routinely ambush police, destroy government buildings including schools and abduct officials.

Just a few short kilometres from the train station and the cheerful train lies the Jagdalpur District Hospital, the region's main health facility.

Flies buzz around open garbage cans where food and medical waste fester. Dozens of terrified-looking villagers squat on the filthy floors besides sick relatives. But at least Jagdalpur has a hospital. The hundreds of villages that surround it are lucky to get occasional visits by nurses who can administer vaccines to their infants or health workers trained to be the first line of defence against cerebral malaria that is endemic to the region.

Local health workers struggle with the dialects spoken by the adivasis - or "original" people - as the tribespeople are called.

"What life was like 30 or 40 years ago in India ... it's still like that in these villages," said Ajay Singh, a health worker in Kondagaon, a group of villages in the district.

Pratap Narayan Agrawal, a lawyer and rights activist, said the government's neglect of the region creates fertile ground for the rebellion to grow.

The government in turn blames the Maoists' violence for blocking efforts to help the villagers.

"They don't want to see roads and buildings. Whether it's a health centre, a school or a hospital," said P Anbalagan, the district's top administrator. "They don't allow roads to be constructed. If there are no roads, how will doctors reach villages?"

The government has struggled to contain the insurgency with little success.

Two years ago the federal government's "Operation Green Hunt" was supposed to flush the rebels from forest hide-outs. In the ensuing months, the rebels killed nearly 100 troops.

After his baby girl's club foot is corrected, Channu only shrugs his shoulders over questions about the government, the rebels and the region's lack of development. He says he never thinks about things like that.

But he does know that the only time someone was able to solve one of his substantial problems, it was aboard the medical train.

"I want the train to keep coming back," he said. "They care about people like us."