It is not the largest diamond in the world, nor even the most flawless. Yet shahs, emperors and maharajas have fought for it, murdered for it and blinded and banished their brothers for it.

One 19th century account of the history of the Koh-i-Noor, Persian for Mountain of Light, says the priceless gem had been "a factor in tragedies innumerable … blurring the fair image of virtue, making life a curse where it had been a blessing, and adding new terrors to death".

But although the Mountain of Light had cast an unfortunate shadow, cursing most who had owned it over the centuries with "an uninterrupted series of calamities and sufferings", in 1849 the British were very happy to help themselves to it.

Since then it has remained in the possession of the British royal family as part of the Crown Jewels - a fact that has niggled successive generations of Indians and the descendants of the boy-maharaja from whom it was taken when he was overthrown in 1849, at the end of the Second Anglo-Sikh War.

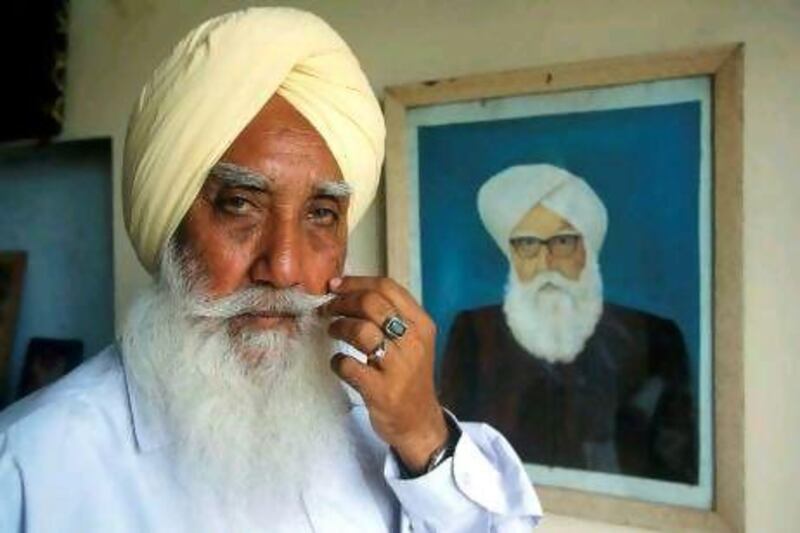

This week Jaswinder Singh Sandhanwalia, a 50-year-old company administrator living in Amsterdam who claims he is a descendant of Maharaja Duleep Singh, announced his intention to launch a civil action in London to recover the diamond.

It isn't, of course, the first time that Indians have sought the return of the stone. The subject came up during Queen Elizabeth II's state visit to India in 1997 and, while on a trip to the country in 2010, the British prime minister David Cameron was obliged to politely refuse its return.

"If you say yes to one you suddenly find the British Museum would be empty," Mr Cameron said, in tacit acknowledgement of how Britannia had once looted the world. "I am afraid to say, it is going to have to stay put."

But even if Mr Sandhanwalia is related to the maharaja, the family's claim to a diamond that throughout its long history has almost always changed hands at sword-point is no greater - although no weaker - than that of Queen Victoria and her descendants.

Many versions of the story of the Koh-i-Noor exist. Most are fanciful, none is purely factual, and some are downright fictional. But one in particular stands out as a work of some academic merit, and the course it charts for the diamond's passage through time shows that few have ever been able to lay true claim to lawful ownership of the Mountain of Light.

The author of The Great Diamonds of the World - Their History and Romance, was Edwin W Streeter, a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society with rather good contacts.

Published in 1882, 30 years after the Koh-i-Noor joined the British Crown Jewels after one of the more bloody episodes in the history of Anglo-Indian relations, his chapter on the diamond was a serious attempt to part fact from fiction - and had been "graciously read and approved" by none other than Queen Victoria, the most recent "owner" of the stone.

For Streeter, the Koh-i-Noor was "preeminently 'the Great Diamond of history and romance'." While it was true that in its story fable had "crept in, as if to try a bout, in romantic revelation, with fact", and "Oriental fancy has strewn the lurid history of the diamond with much traditional gloom … human invention is outdone by the reality of human depravity and human woes".

Streeter's research, carried out in Britain and India, led him to conclude that the diamond's first appearance in history was in 1304, when it was acquired by force by Alauddin Khilji, ruler of the Turkic Afghan Khilji dynasty in Delhi, after his defeat of the northern kingdom of Malwa.

Two centuries of obscurity then followed until the diamond resurfaced on May 4, 1526, in the memoirs of Sultan Babur, the Muslim founder of the Mughal Empire in India and a direct descendant of Tamerlane, the Mongolian-Turkic conqueror of central Asia, Persia and India.

After the defeat and overthrow of the Afghan Lodi dynasty at the Battle of Panipat, the diamond was presented as a tribute to Babur's son Humayun, whose troops slew Bikermajit, the Hindu Rajah of Gwalior.

Babur's memoirs claim that when Bikermajit's family was captured Humayun "did not permit them to be plundered. Of their own free will they presented to Humayun a peshkesh [tribute], consisting of a quantity of jewels and precious stones".

Free will? Well, he would say that. Regardless, among the haul was a stone deemed "so valuable that a judge of diamonds valued it at half the daily expense of the whole world" - the Koh-i-Noor.

Babur recorded that the diamond had been acquired 200 years earlier by Sultan Alauddin.

A member of the Khilji Dynasty, which succeeded the Ghuru and ruled over most of India from 1288 to 1321, Alauddin had seized the diamond in 1304 after defeating the Rajah of Malwa, "in whose family", noted Streeter, "it had been an heirloom from time out of mind".

This is the one story about the diamond with any kind of documentary provenance and, concluded Streeter, it showed that "the gem was at all times regarded as the property of the Rajahs of Malwa", which would seem to put paid to Mr Sandhanwalia's claims.

On the other hand, his supposed forebears, unlike the perfidious English, did at least acquire the stone by the novel method of paying for it. Sort of.

In 1739, the Persian ruler Nader Shah invaded India and, following the well established tradition, helped himself to the diamond, then in the hands of the Mughal emperor Mohammed.

By 1751 the Persians were on the back foot, and Shah Rokh, Nader's son, used the diamond to buy an alliance with Ahmed Shah, founder of the Durrani Afghan empire.

History's wheel turned again and in 1813 Shah Shuja, Ahmed's descendant, was dethroned, blinded and driven to seek exile at the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the "Lion of the Punjab", founder of the Sikh Empire - and, Mr Sandhanwalia says, his ancestor and ticket to ownership of the Koh-i-Noor.

According to Streeter, Shuja was less a guest and more a prisoner of the Maharaja, who forced him to sell him the diamond for 125,000 rupees.

In 1839, the Maharaja's dying wish was that the stone should be given as an offering to a Hindu temple in Orissa. But his relatives were less keen on the idea, which is how the Koh-i-Noor was still in the Lahore treasure room when the British came to town in 1849.

Having finally secured victory over the troublesome Punjab at the end of the bloody Anglo-Sikh wars, the British were in the mood for payback.

The stone, secured for Her Majesty by the Marquess of Dalhousie, the British governor-general of India, was among the property of the state confiscated "in part payment of the debt due by the Lahore government and of the expenses of the war".

Not that the British royals were overly impressed by it. The Queen's husband, Prince Albert, personally took charge of the recutting of the stone, deemed necessary because, according to Streeter, "it had been so unskilfully treated by the Indian cutter that it looked little better than an ordinary crystal".

When the Prince Consort got his hands on it, the Koh-i-Noor weighed a little more than 186 carats - about 0.0372 kilograms. By the time he was through, it was down to 106 carats.

By comparison, the Cullinan I, or Great Star of Africa, the Koh-i-Noor's neighbour in the British Crown Jewels and until 1985 the largest diamond in the world, weighs in at just over 530 carats.

Cutting the Koh-i-Noor was no easy job, complicated by a significant flaw. Work began on July 6, 1852, and took 38 12-hour days to complete.

"The result," noted Streeter, "was far from giving universal satisfaction. The Prince Consort … openly expressed his dissatisfaction with the work".

Nevertheless, the diamond was ready in time for the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations in 1852. It took pride of place in the Crystal Palace in London's Hyde Park.

According to The Times, it was "decidedly the lion of the Exhibition. A mysterious interest appears to be attached to it … the crowd is enormously enhanced, and the policemen at either end of the covered entrance have much trouble in restraining the struggling and impatient multitude".

Prince Albert and the London crowds weren't the only ones fascinated by the diamond. Victoria, Streeter noted with evident pride, agreed to read a first draft of his Koh-i-Noor chapter "without requesting any correction or alteration in the leading points of our history". No one, added Streeter, "has studied more carefully the records of India than the Queen".

And it is, no doubt, that careful study that accounts for the superstition-driven fact that the diamond has been worn only by female members of the British royal family - Queen Alexandra, Queen Mary and most recently, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, the wife of George VI, the last Empress of India and mother of Elizabeth II, Britain's reigning monarch.

It was last seen in public in April 2002, when the Queen Mother's coronation crown, bearing the diamond, was placed on her coffin as she lay in state in Westminster Hall.

According to one account, the supposed curse of the diamond was first noted in a 14th-century Hindu text, which held that: "He who owns this diamond will own the world, but will also know all its misfortunes. Only God, or a woman, can wear it with impunity."

Mr Sandhanwalia, who is clearly neither, should perhaps consider this before taking his claim much further.