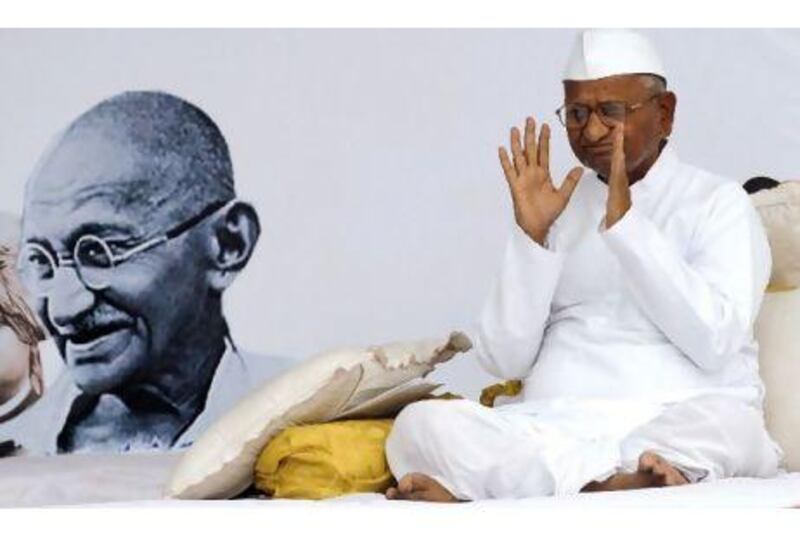

NEW DELHI // The Indian government late Friday gave in to the demands of Anna Hazare, an activist who had been on a public fast since April 5 asking that an anti-corruption bill be drafted jointly by lawmakers and social activists.

But while Mr. Hazare's protest has been successful, his tactic has sparked a debate about the ethics and legitimacy of the fast, which was used to great effect by Mahatma Gandhi against the authoritarianism of the British Raj. But critics questioned the relevance of a fast within a constitutional democracy.

Writing in The Indian Express newspaper, political commentator Pratap Bhanu Mehta observed that there was "something deeply coercive about fasting unto death. When it is tied to an unparalleled moral eminence, as it is in the case of Anna Hazare, it amounts to blackmail."

Mr Hazare is well-known in India as a Gandhian, one who follows the precepts of life as set down by Gandhi. More than a dozen times over three decades, Gandhi embarked on a fast unto death to protest policies that he considered unfair or to force a resolution to an impasse.

The first occurred in 1918, when Gandhi was protesting the poor treatment of labourers by mill owners in Gujarat. The hunger strike was a success, but Gandhi admitted to misgivings about it.

Victory, Gandhi would later write, is "not quite pure, as the fast I had to observe … exercised indirect pressure upon the mill owners."

Perhaps the most famous of Gandhi's fasts came in 1932, when he fought separate electorates for the lower castes of Hindus then known as the untouchables. After Gandhi had fasted for five days, the political representative of these castes, Dr BR Ambedkar, succumbed to the pressure and signed the Poona Pact, named after the city where Gandhi had undertaken his fast.

Dr Ambedkar, one of the architects of India's constitution, later criticised tactics such as the fast. Where "constitutional methods are open, there can be no justification for these unconstitutional methods," he said in a 1950 speech that has been quoted often in the Indian media over the past week.

"These methods are nothing but the grammar of anarchy and the sooner they are abandoned, the better for us."

In independent India, the fast has been used most often by people who were already well-entrenched in the political establishment. Mamata Banerjee, an opposition leader in the West Bengal state government, declared a hunger strike in late 2006 to protest a corporation's acquisition of farmers' lands.

In 2009, politician K Chandrasekhar Rao went on a public fast to press for a separate state of Telangana to be formed out of the state of Andhra Pradesh. This echoed, in a way, the birth of Andhra Pradesh itself, which was created after a Gandhian named Potti Sriramulu died after fasting for 82 days in 1952. Mr Sriramulu was demanding that an Andhra state be carved out of the erstwhile Madras Presidency region.

Even incumbent political leaders have found the fast to be effective. During the general elections in 2009, the Tamil Nadu chief minister M Karunanidhi called a fast to show his solidarity with Tamil rebel groups in Sri Lanka.

Accompanied by a large retinue and mobile air conditioners, Mr Karunanidhi, then 84 years old, set up in public view on a stage in the city of Chennai. The fast started shortly after an early breakfast and ended well in time for lunch.

Over the last decade, though, the most visible hunger striker has been Irom Sharmila, an activist from the state of Manipur. He began a fast in November 2000, protesting a law that gave the armed forces enhanced powers in her state.

Nitin Pai, a geopolitics fellow at the Takshashila Institution, an independent, Chennai-based think tank, said that civil disobedience "in general and hunger strikes in particular must be used in the most exceptional circumstances, where constitutional methods are unavailable or denied... I'd compare this to the right to self-defence."

Mr Hazare's fast evoked considerable support across the country, with simultaneous demonstrations springing up in other cities. Prabir Ghosh, the general secretary of the Kolkata-based Science and Rationalists' Association of India, pointed to this support as a testament to the legitimacy of Mr Hazare's fast.

"This is why I don't think this fast can be called blackmail," Mr Ghosh said. "A fast can put pressure on a government only when the mass public sides with the person fasting. There's so much support here for Anna Hazare. That shows that the cause is a popular one."

Mr Pai, however, warned against large numbers of people being mobilized around "an oversimplified miracle cure", and he equated the fast to coercion.

"If we are to allow that hunger strikes and street protests do better than constitutional methods, then how would you decide issues where there are sharp differences?" Mr. Pai said. "If two Gandhians go on hunger strikes asking for polar opposites, do we settle the issue by seeing who gives up first?"

SSubramanian@thenational.ae