NEW DELHI // They are bright, vibrant and colourful, and they say "India" more eloquently than any travel brochure.

Hand-painted signs with unique lettering and designs decorate everything from bicycles to buses, from small shops to the sides of whole buildings.

For years, however, they have slowly been disappearing, replaced by computer-printed versions - less imaginative, but faster and cheaper. Now a graphic designer is harnessing that same computer power to preserve the art of skilled street painters across India by digitising their typefaces.

"When this started disappearing from the streets, I realised we were losing a part of our street art culture," says Hanif Kureshi.

Mr Kureshi, 30, runs Hand Painted Type, which is dedicated to preserving those unique fonts by making them available online. When he sells them to clients, half the money goes to the artist.

The art director of an advertising agency, Mr Kureshi lives in Delhi but grew up in Talaja, a small town in Gujarat, and has been always fascinated by Indian street signs.

It was on his holidays as a child to the city of Ahmedabad, in Gujarat, that he had his first brush with street-art painters. This was where he met an artist, who called himself Painter Salim, designing car licence plates. "For four days, I would just sit at his shop and watch. It was an unspoken internship."

Encouraged by his father to study art, Mr Kureshi graduated in 2002 with a master's degree in fine arts and went on to become a graphic designer. He is maintaining his love of typography through this preservation project.

"Every small town in India has its own culture and customs and rules, and that is reflected in the design of the sign boards," he says.

"They are very minor things that an ordinary person may not notice but a sign board in Chennai does not look like one in Delhi."

It was 2008 when Mr Kureshi realised that hand-painted signs, made mostly of metal or wood, were slowly being replaced in Delhi by computer-printed signs on vinyl cloth. As the project grew, over the past few years he has travelled across cities and towns in India, tracking artists down by the phone numbers commonly written under their signatures.

He then commissions the artists to create their unique fonts in numbers, English and a regional Indian language before turning them into a computerised font that can be downloaded from his website. Mr Kureshi has so far collected more than 50 different fonts.

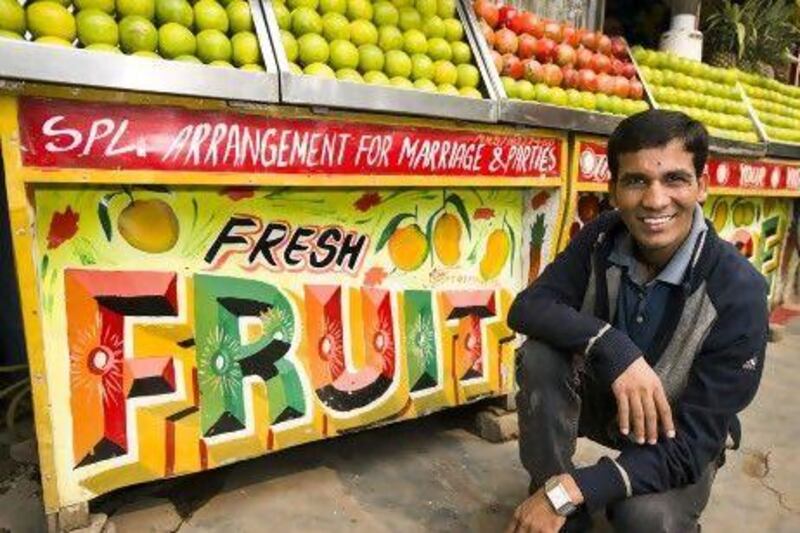

Among those to benefit from his project is Akhlaq Ahmad, who put himself through art school painting sign boards for fresh juice stands.

"I gave these signs the 3-D effect, and used neon colours," he recalls with pride.

Soon word spread. His work was in demand. Four years ago, when Mr Ahmad was 23, he used to work until 1am painting two or three boards, sleep at a juice shop and, during the day, head to school for his fine arts degree at the Jamia Milia University in Delhi.

Life was good. He was one of a handful of sign painters in Delhi and he designed up to 1,000 boards a year.

His brightly coloured handwritten boards were a hit, but it was a trend that didn't last. Signs that he painted just a few years ago are now gone, replaced by computer-generated ones.

"My work from the streets will be gone soon, so I need to move on as well," he says.

Mr Ahmad's story is gaining worldwide attention through Mr Kureshi's typography project. As a teenager, he ran away from home to avoid becoming a farmer. He found work in Mumbai cleaning the brushes and palettes of painters in the studio of a Bollywood poster painter, where he learnt the special calligraphy used on Bollywood posters.

"Director's name in English, film's name in Urdu, actors' names in Hindi. I slowly learnt by watching what they did," Mr Ahmad says.

His big break came after he moved to Delhi. He sought out a Bollywood poster painter in the city, who took him in and said: "I don't care if you worked in Mumbai or London. Show me what you can do."

Mr Ahmad says: "He gave me a brush and I showed him what I learnt and I was employed."

His friends in the city were men from the villages in the Bahraich district of Uttar Pradesh who ran a near-monopoly on the juice stands in Delhi.

"They would tease me, why don't you decorate our sign boards? Are you too good for us, Mr Bollywood man?

"They turned me into the fruit-juice sign guy," said Mr Ahmad, who uses the tag name Painter Shabbu.

While his neon-coloured fonts have yet to sell on the website, short films made by Mr Kureshi about the unique typefaces and the lives of the artists have been shown at international design conferences, including the annual meeting of the International Typography Association in Reykjavik, Iceland, last September.

"There are lots of artists around me who I see, who cannot rise because they have no support," says Mr Ahmad. "But I had support of Mr Kureshi's project, which helped me get an education. I have a portfolio and a story to tell about my work. People know me now."

Sunil Kumar, 44, who uses the professional name Painter Umang - which means happiness in Hindi - is also proud to be included in Mr Kureshi's project.

His work, as with all the sign painters of India, is unique, with a distinct flavour that draw influences from Bollywood posters, regional Indian scripts and the desire to have his handiwork visually stand out in the country's crowded marketplaces.

"We are artists," he said. "When we are in the mood, a piece can take half an hour. If the mood is going sour, we stop. We are not machines."