NEW DELHI // A year on from the Commonwealth Games in New Delhi, the stadiums lie unused, corruption scandals are emerging by the day and the event's senior organisers are in jail.

But the troubled event may yet go down as a positive turning point in India's history.

The most surprising legacy of the Games has been the scale of the political fallout that has engulfed the government in the past year.

The strength of public anger over the wastage and humiliation of the Games helped spark a wider movement against corruption, spearheaded by the hunger strikes of the activist Anna Hazare in August that have destabilised the government and dominated the political agenda.

Arvind Kejriwal, known as the architect of Mr Hazare's protests, has said it was the Commonwealth Games that first showed him the possibility of mobilising massive public support against corruption.

Boria Majumdar, a journalist and author of Sellotape Legacy: The Commonwealth Games and Delhi, said it would have been impossible to anticipate the scale of the fallout that has occurred.

"But, ultimately, it has shown that you can't take democracy for a ride. These games were for the people, not the government," Mr Majumdar said.

When the opening ceremony for the Games finally got under way on October 5, 2010, there was a tangible sigh of relief across India that the event had started at all.

For months, the local media had presented a daily digest of endless delays, dodgy deals, collapsing infrastructure and outbreaks of disease across the city.

When the international athletes arrived, images of faeces-smeared rooms in the athletes' village made front pages across the world, turning India's promised coming-out party into a source of national humiliation.

Despite an impressive opening ceremony that seemed to confirm the organising officials' promise that everything would work out in the end, several of those officials, including the Organising Committee chairman, Suresh Kalmadi, and secretary general, Lalit Bhanot, are now in a Delhi jail.

They are accused of being involved in massive irregularities in the awarding of contracts for the Games. Trials are expected to begin in November.

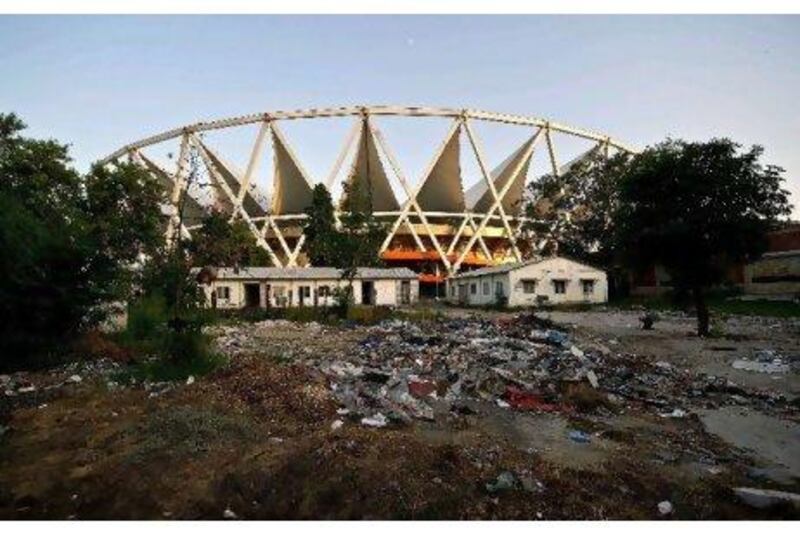

Meanwhile, Jawaharlal Nehru stadium, which formed the centrepiece of the Games, has not been used for a single sporting event in the past 12 months.

Vijay Kumar Malhotra, acting president of the Indian Olympic Association (IOA) has described it as the "most expensive junkyard in the world", with rubbish surrounding the outside and the tracks falling into disrepair.

"The government has spent billions of rupees on this infrastructure but in the last year, no sportsmen have been allowed to use it," Mr Malhotra said.

The same is true for almost all the 17 venues built or renovated ahead of the Games. Despite the appearance of new training grounds for hockey, shooting and cycling, sportsmen have preferred to stay at their usual camps in other parts of the country, particularly around Mumbai and Pune.

Mr Majumdar said: "Was there any kind of legacy plan for how these stadiums could be used after the Games? I don't think so.

"Things are beginning to rust. If these facilities go unused, all this money will have been wasted."

Part of the problem is a bitter power struggle between the IOA and the Ministry of Sports which has frustrated Olympic hopefuls' hopes of using government facilities..

"There is some antipathy there," Mr Malhotra admitted. "We have not had a single meeting with the Ministry of Sports ever since they tried to introduce a bill that would give them control over our organisation."

It was reported yesterday that the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC), the government's anti-corruption watchdog, is investigating irregularities in a total of 97 Commonwealth Games-related projects. They range from the awarding of broadcasting rights and construction to the purchase of toilet rolls, which famously cost the organisers US$80 (Dh293) each.

Other embarrassments include the Shivaji Stadium, which was meant to serve as the practice venue for hockey, but which is only finally due to be ready this December, some 14 months after the Games finished.

Another damaging aspect of the Games' aftermath has been the failure of government agencies to pay foreign companies, adding to India's reputation as a bureaucratic quagmire for investors.

An estimated US$85 million is owed to 20 contractors, who are caught up in the CVC investigations. THE UK-based SIS Live, which ran international broadcasting of the Games, says it is owed US$23 million withheld after a CVC probe accused it of contract irregularities.

The company, which has been backed by the British High Commission, dismisses the investigation as full of "misrepresentations, inaccuracies, false assumptions and unjustified conclusions".

There are still hopes for the future of sport in India. A new National Institute for Sports Science and Medicine is under construction near Nehru stadium. It promises state-of-the-art coaching facilities and appears to be on schedule for its planned opening in April 2012.

Mr Hazare's protest, fuelled by months of government scandals, has prompted promises of reform from the ruling coalition and opposition parties alike.

Mr Majumbar said that this could be India's turning point.

"If the legacy of the Games is that it gave a rude awakening to officials, and raised the hope that good governance might become a reality in this country, then they will be celebrated for centuries to come," he said